Tanzania is located at the intersection of several East African countries and its population of around 47 million consists of more than 120 ethnic groups. Bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west and Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique to the south, the country’s eastern border is formed by the Indian Ocean. The name ‘Tanzania’ derives from the names of the two states, Tanganyika and Zanzibar, that joined in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania.

The Tanzanian economy is dominated by agriculture, with the industry accounting for around 80% of employment. Currently hydrocarbon production is limited to natural gas from the Songo Songo gas field, located offshore in the Indian Ocean, on Songo Songo island, about 15 km from the Tanzanian mainland and 200km south of the commercial capital Dar es Salaam. Production commenced in 2004 with the gas being transported by pipeline to Dar es Salaam, where it is converted to electricity. A new gas field is being brought on stream in Mnazi Bay, south-eastern Tanzania, with first gas expected to be delivered Q1-2015.

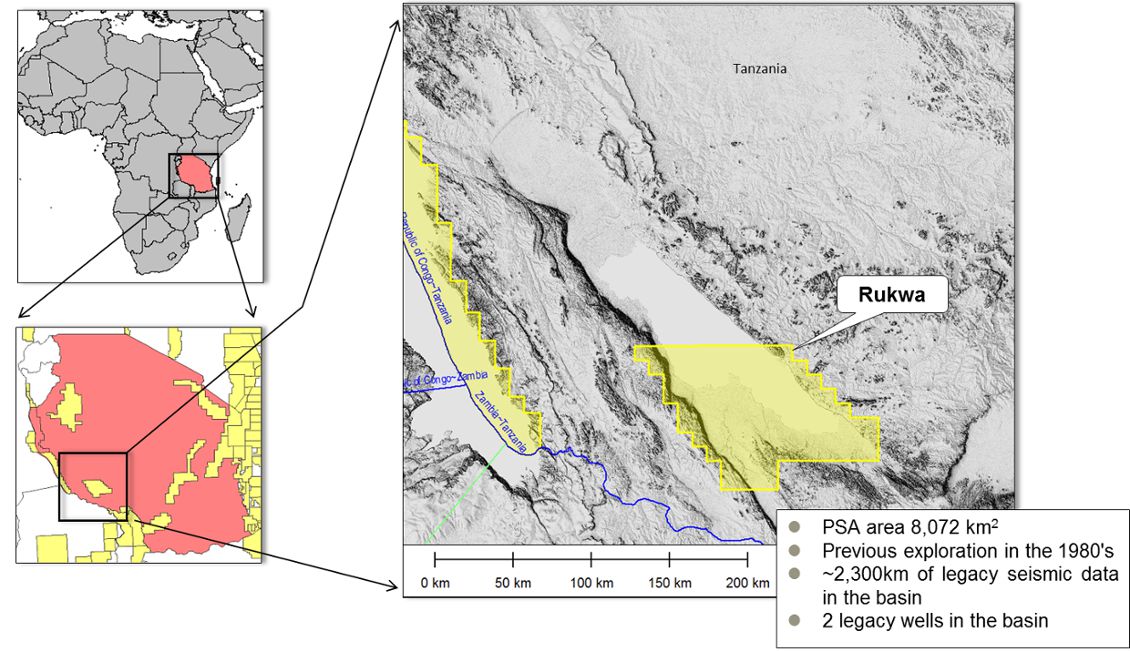

Heritage Oil is an independent exploration and production company with producing assets in Nigeria and Russia and exploration assets in Tanzania, Papua New Guinea, Malta, Libya and Pakistan, looking for areas where it can participate as an early entrant. The company has two blocks in Tanzania, which are considered to have analogues with the Lake Albert Basin in Uganda.

Exploring Rifts

In 1997 Heritage Oil began to explore in the Albert Basin, Uganda, on the western arm of the East African Rift System (EARS). By 2008 drilling in the Kingfisher area had resulted in exploration success and individual well flow rates of over 14,000 bopd caught the eye of the watching industry. Current reserve estimates for the Albertine Basin stand at 1 Bbo, with upside for 2 Bbo – though upside estimates of up to 3.5 Bbo have been quoted. The Kingfisher well was a game changer and opened a new fairway in the African Rift Basins. Since its discovery, stimulation of exploration activity has resulted in the African rift basins becoming nearly 100% licensed.

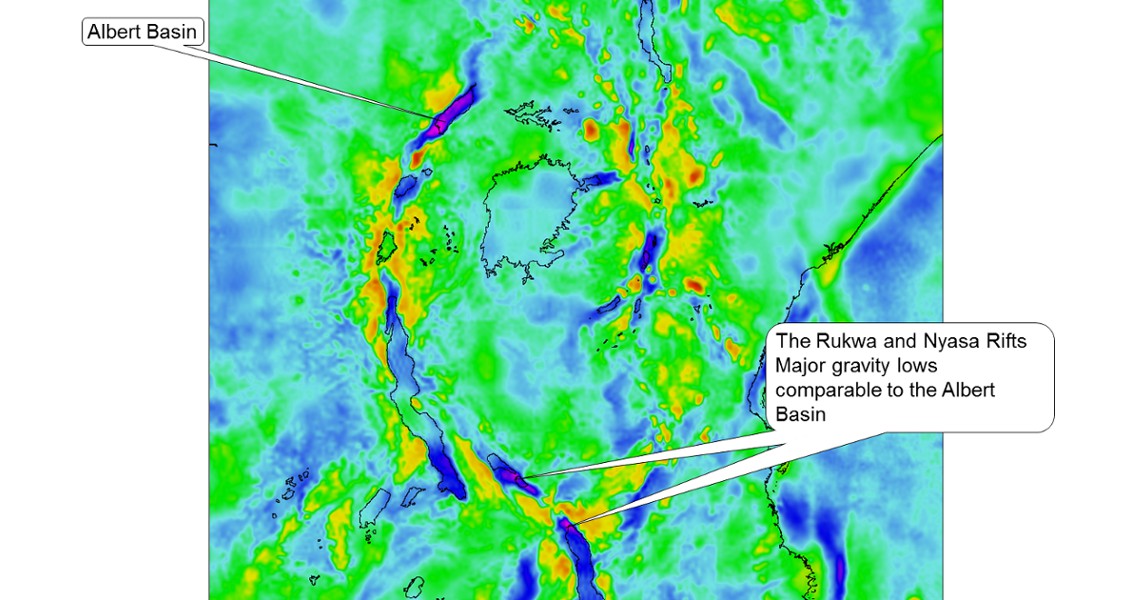

Following its Albertine Basin success, Heritage was keen to apply its geological and operational skills to exploring in similar African rift basins. As part of the screening process it used the global gravity database to look for basins with thick low density sequences, which may be geologically similar to Lake Albert. This pointed them towards the Rukwa Rift and the northern end of the Nyasa Rift, where gravity lows comparable to the Albert Basin are present.

As a part of operations in Uganda, Heritage reviewed the operational logistics of drilling in an offshore riftlake location. Outline cost for drilling in a comparatively shallow (<50m) lake was in the order of $85 million – just to mobilise the rig/barge into the lake; for deeper waters the costs were considerably higher. The conclusion was to keep rigs onshore or in very shallow water and this increased the interest in Rukwa, the shallowest of all the major lakes.

Bob Downie, Senior Geologist with Heritage Oil, explains why the licences attracted Heritage: “Our experiences in the Albert Basin in Uganda showed that the petroleum system is entirely contained within the Neogene section, so we were very encouraged in that not only do the Rukwa and Nyasa rift basins have thick Neogene Lake Bed sequences but also have underlying Cretaceous and Karoo, providing secondary potential for reservoir and source rocks.”

Neogene Source Rocks

Geological map of the Lake Rukwa and Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) area, showing surface outcrops, key bounding faults and well locations. (Modified from Roberts et al. (2010), DOI 10.1016/j.afrearsci.2009.09.002)Exploration in the Rukwa Basin by Amoco in the mid-1980s resulted in the acquisition of ~2,300 km onshore and offshore legacy seismic data. Two wells were also drilled in 1987 – Galula-1 and Ivuna-1. Legacy data delineated a major depocentre with up to 4,500m of Plio/ Miocene to Recent section. Heritage considers this an underexplored basin with missed potential.

Geological map of the Lake Rukwa and Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) area, showing surface outcrops, key bounding faults and well locations. (Modified from Roberts et al. (2010), DOI 10.1016/j.afrearsci.2009.09.002)Exploration in the Rukwa Basin by Amoco in the mid-1980s resulted in the acquisition of ~2,300 km onshore and offshore legacy seismic data. Two wells were also drilled in 1987 – Galula-1 and Ivuna-1. Legacy data delineated a major depocentre with up to 4,500m of Plio/ Miocene to Recent section. Heritage considers this an underexplored basin with missed potential.

A frequent criticism of the source rock potential of Lake Rukwa has been that the present-day shallow water depths would be inconsistent with deposition and preservation of source rocks. Bob Downie elaborates: “Our studies clearly show that the Neogene palaeo-Lake Rukwa was deep for significant periods of its history. Deep water represents a high probability of source rock deposition and preservation.”

Geochemical analysis of Ivuna-1 cuttings clearly indicate that oilprone Type I kerogen comprises 80–95% of total kerogen and supports the proposition that the deep water dysaerobic conditions existed for significant periods during the Neogene. Ivuna-1 is on the basin margin and it is likely that the source quality and thickness will increase into the basin depocentre.

Source rocks are one thing but what about maturity? Bob Downie again: “Our current mapping and velocity models suggest that the base of the Lake Beds in the basin depocentre is up to 4,500m. The legacy wells both showed high geothermal gradients of 39°C/km and modelling suggests the possibility of oil generation from depths > 2,200m. With this in mind we can define a kitchen within the Lake Beds.”

Potential Reservoirs and Seals

The legacy well data and outcrops prove the existence of medium-coarse grained quartzitic Lake Beds sands with good potential as reservoir. Downie and co-workers consider the probability of effective reservoirs being present in the mapped leads as being highly likely. Shales with seal potential were penetrated by the legacy wells and similar shales, at similar stratigraphic levels, can be recognised in both legacy wells. With this in mind, Heritage considers the probability of effective seals as being good.

If all this is true then it is important to try to understand why the initial wells failed. The team at Heritage believe that Ivuna-1 could have never worked, as it was drilled 40 km from the main kitchen area, in a migration shadow zone. Galula-1 was more favourably located but the structure was not closed to the south-east and was located in a proximal, sandy, nonsealing facies. Also, faults in this area appear to be non-sealing.

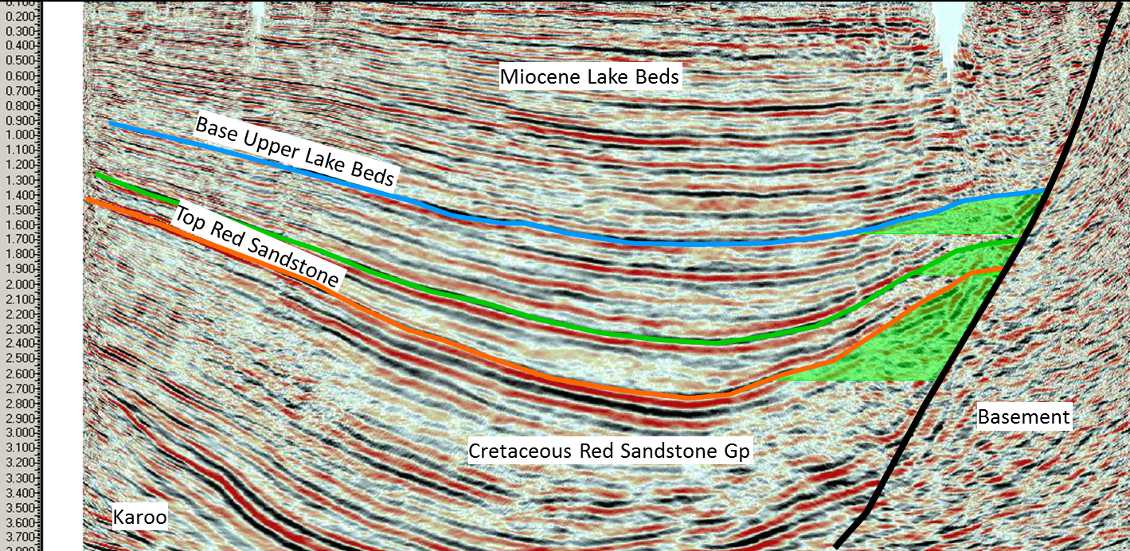

From the legacy seismic it was recognised that Rukwa had structures of probable strike-slip origin, giving rise to the possibility that structural traps similar to the Albert Basin Kingfisher field may be present. In fact, the legacy seismic suggested a number of leads of this type associated with the main basin margin fault, proximal to the depocentre, in areas that were poorly covered by the legacy seismic.

In order to remedy this deficiency in seismic coverage Heritage acquired an additional 601 km of seismic. 460 km of this were acquired in the offshore areas using the same ocean bottom cable (OBC) technology as applied to Lake Albert, and 141 km were acquired using conventional land dynamite technology. The focus was to image structures right up to the basin margin fault. The results were successful and prospects defined by roll-over structures against the fault were proved at a number of locations.

Exploration – Kyela, Lake Nyasa

This onshore area north of Lake Nyasa has never previously been targeted for hydrocarbon exploration, but Heritage was drawn to it by the recognition of a major gravity low. The possibility of a major depocentre was confirmed by published seismic maps from the immediate offshore area, which show up to around 4 seconds of section.

As the first phase of the exploration campaign, Heritage acquired a Full Tensor Gravity (FTG) survey, by Arkex, completed in September 2012. The results were very revealing, confirming the presence of the main depocentre, extending from onshore to offshore. The data suggest the presence of flanking structural highs and intra-basinal highs. Some of these are very large with the ‘A’ Lead being around 50 km2.

As a result of the FTG a 100 km reconnaissance seismic programme was sited and acquired, which proves reflectors down to over 4 seconds and validates the gravity highs shown by FTG as potential structures. The seismic thus provides clear evidence that sufficient thickness of section exists to promote potential source rocks into the oil window. In order to validate the presence of a kitchen, a geochemical microseep was commissioned from AGI across the main depocentre and onto the flanking highs. This survey showed that the basin centre was characterised by low hydrocarbon signals, whereas the flanks had high signal, exactly as might be expected if hydrocarbon generation had occurred in the basin centre with migration to the basin flanks.

A second seismic infill programme is planned, to convert the gravity leads to seismically defined prospects.

Looking Ahead

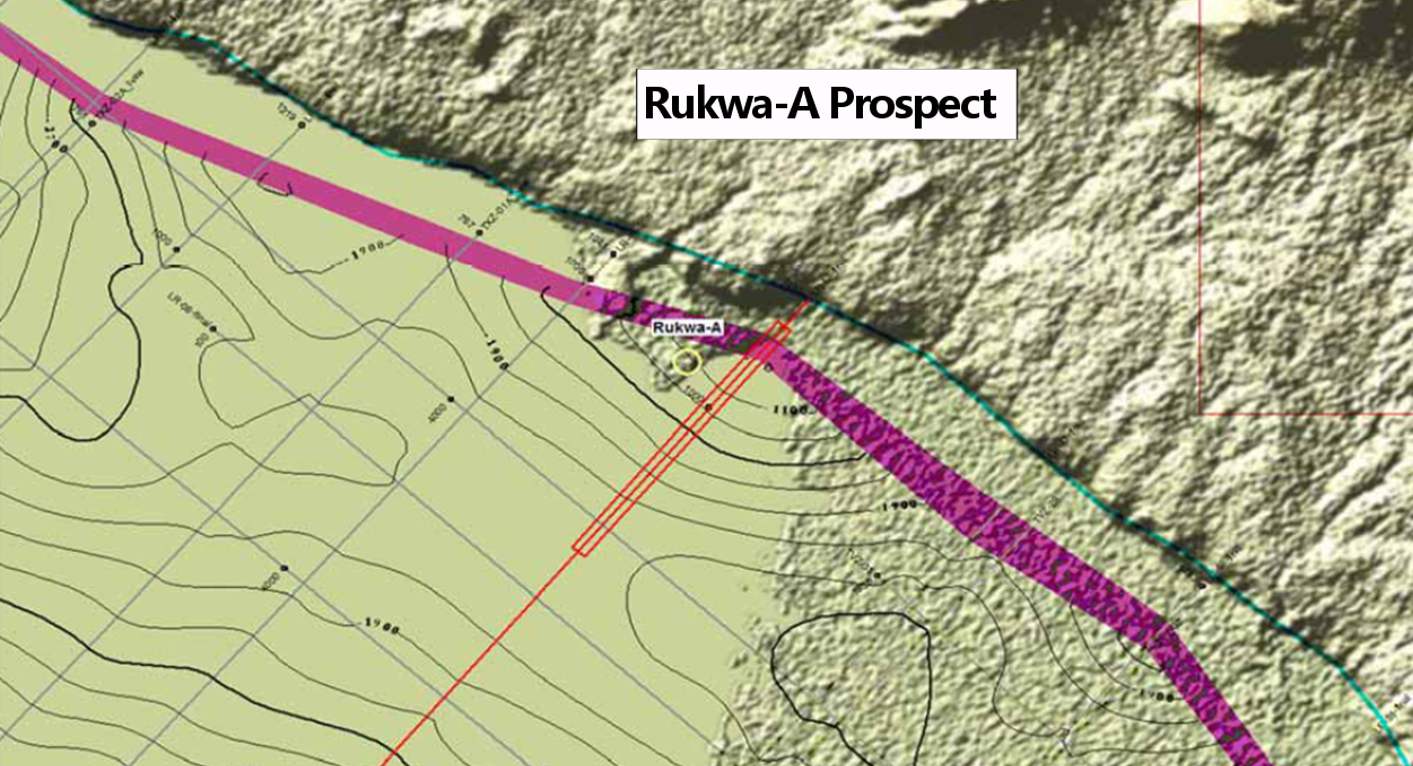

At Rukwa, Heritage has completed the mapping of the combined seismic dataset and has defined five prospects associated with inversion structures along the main boundary fault. The largest of these prospects, Rukwa-A, located at the southeastern end of the lake, has an unrisked Pmean resource of 225 MMboe (management estimate). The greater part of the structure lies offshore, but the location of a suitable land spit means that the prospect can be tested from a planned onshore vertical well.

Meanwhile, Bob Downie and colleagues believe that the initial geophysical and geochemical surveys of Kyela have proved that this frontier area has clear hydrocarbon potential, with depth of section, potential structures and geochemical anomalies all revealed. The seismic data, however, are insufficient to define a well location and Heritage is planning for an infill seismic campaign to define a well and identify a drilling site location.

The pursuit of hydrocarbons in these blocks will present many scientific challenges, but the geological and geophysical studies undertaken by Heritage to date all point to the clear hydrocarbon potential of both areas. Further geophysical studies will be required in Kyela to delineate drill sites and ultimately the presence or absence of hydrocarbons will be proved by drilling. Nonetheless, Heritage is excited about the similarity of these basins to the proven African Rift Valley plays of the Albert and Lokichar Basins of Uganda and Kenya, and look to extend the proven play into these two underexplored basins