Just as Aberdeen in Scotland – where this article was written – is sometimes referred to as the “Silver City”, the village of Broken Hill in southeastern Australia is described in the same way. But where in Aberdeen this nickname comes from the shiny character of the locally mined white granite, in Broken Hill, it is thanks to the massive silver ore bodies that have been mined for a long time. And still are.

Now, one of the mines in the area, Perilya’s Potosi Mine, located to the northeast of Broken Hill, will also be used for a purpose one would not quickly think of: Compressed air storage. Or better: Advanced Compressed Air Energy Storage (A-CAES). At a depth of around 500 m, the mine infrastructure provides access to a type of rock that lends itself well for air storage, because it is very tight: The Potosi Gneiss.

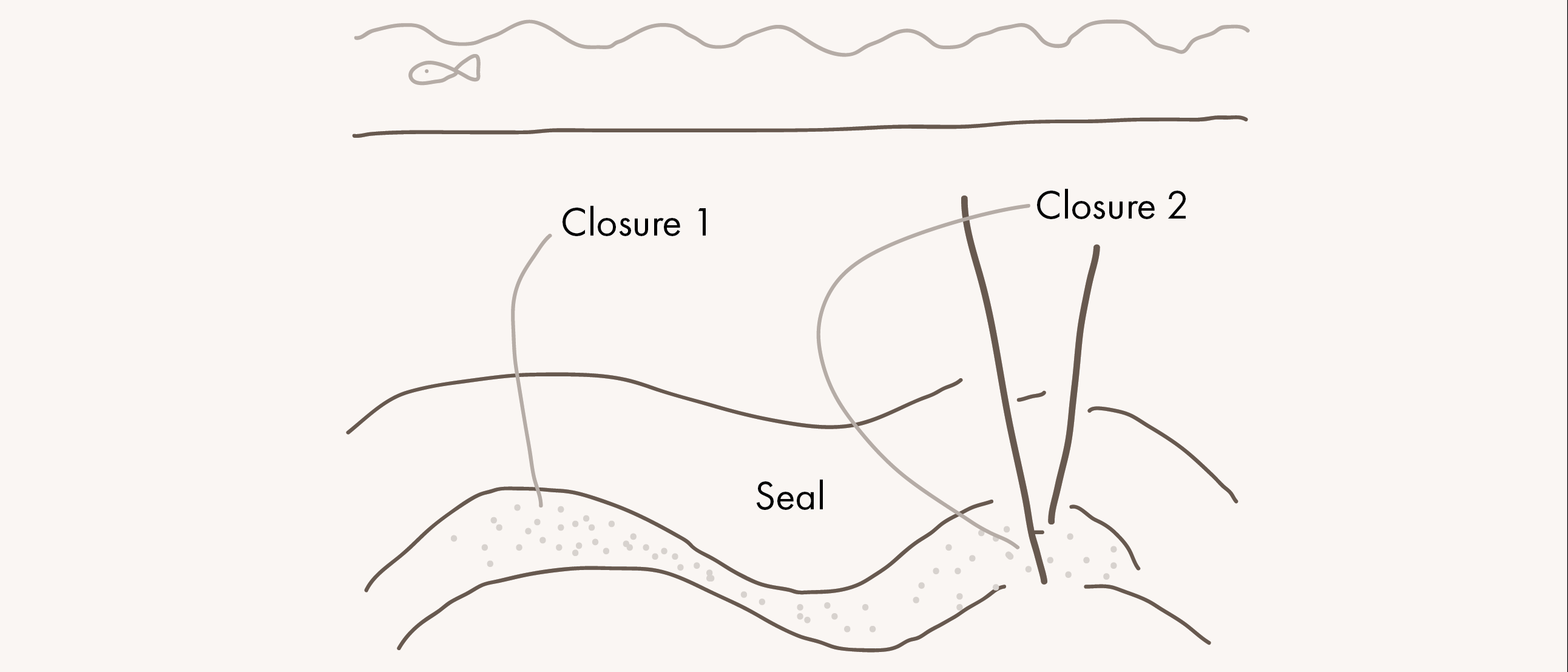

“The target geology was selected since it has extremely low permeability,” a spokesperson from Hydrostor in Canada, the developer of the project, said to us. There are sparsely spaced fractures, but these are very tight and part of the rock mass. “Combined with a very high rock strength, this lithology formed an attractive target for this project.”

To better investigate the local rock properties, extensive in-situ permeability testing has been performed on the host rock geology through the cavern location to confirm that the formation has suitable containment for A-CAES use. These tests showed that the geology has extremely low permeability indeed, and subsequent leakage modelling has demonstrated that the cavern will have negligible air loss over time.

ROUND AND ROUND

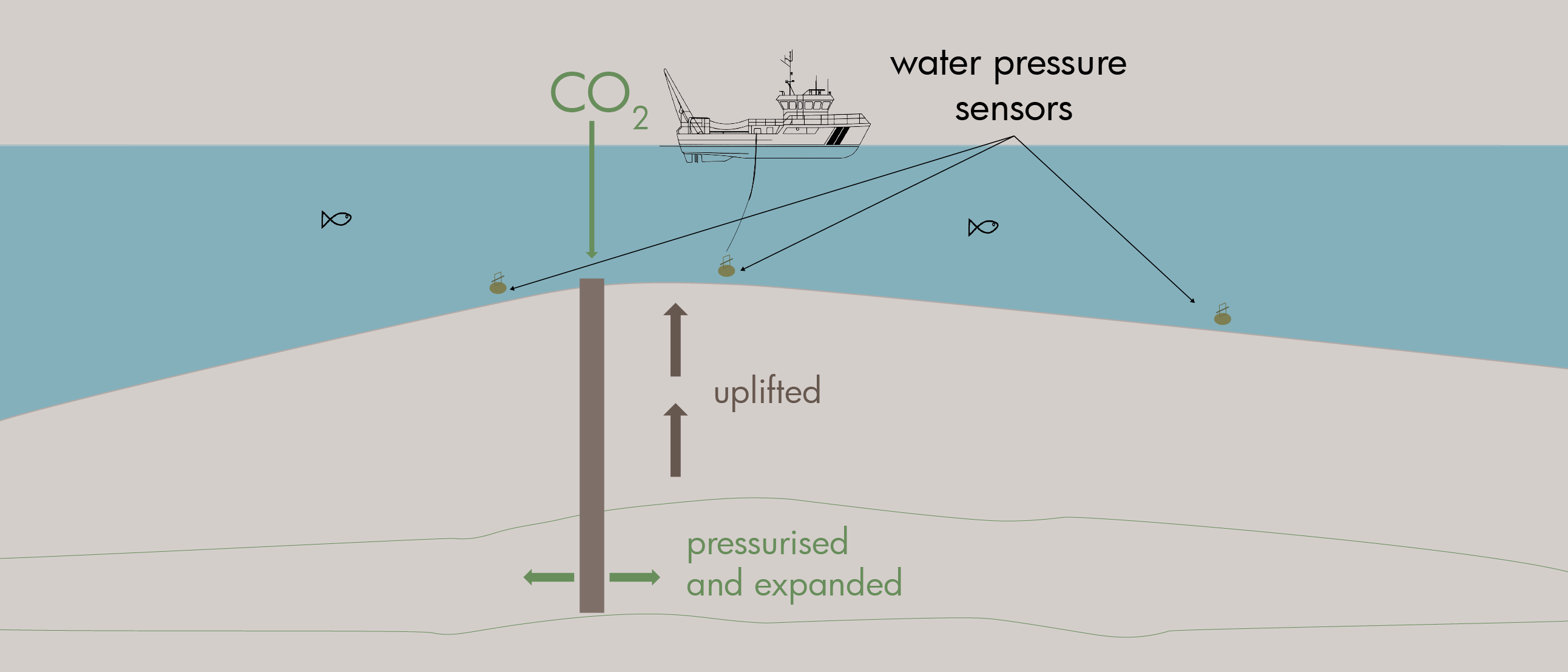

The principle behind compressed air storage starts with excess electricity being used to compress air and pump it into the cavern. When the energy is needed, a connected water reservoir is opened up, allowing water to move into the cavern as the air makes its way to a turbine at surface where the electricity is generated. The process is reversed when the cavern is full of water.

It is the existing mining infrastructure that forms the cost-saving; work on constructing the cavern in which the air will be stored in, can begin much faster this way. And once construction has finished, the cavern will be sealed off from the mine access using a massive monolithic concrete bulkhead. A monitoring system will also be put in place to support cavern operations, including ongoing measurement of the level of air within the cavern.

Once in operation, the project will provide crucial long-duration energy storage capacity and stability to the Broken Hill region and the wider network, with a total capacity of 200 MW and 1,600 MWh (8 hours of storage duration at full output). As such, the new energy storage facility will replace ageing diesel generators, nearing their end-of-life, and will also form a useful buffer for excess electricity generated during peak times.