In the UK’s polarised energy debate, oil and gas exploration occupies an apparently conflicted position. To some, exploration signals future hydrocarbon supply despite the IEA saying that investment in new supply must cease. Conversely, elevated oil and gas prices are driven by demand, signalling the need for increased supply. In the UK’s ambitious net zero regulatory context, exploration can make a positive contribution to energy security, emissions reduction, local employment and revenue and tax generation to facilitate and subsidise future renewables growth.

The UK’s Exploration Task Force (XTF) is a group of industry volunteers collaborating with the regulator – the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), formerly the Oil and Gas Authority – to make the most of UK exploration through the energy transition. In 2021 the XTF issued information packs (utilised in this article), addressing E and A for CO2 storage and the case for responsible upstream investment in the UK. These overlapping themes are contextualised here by the UK upstream industry’s ambitious and uncommon commitment to net zero by 2050 and considerations including supply, demand and the global emissions impact of UK fossil fuel consumption.

Fast-Changing Global Picture

Prior to the Ukrainian invasion, a gas supply imbalance was driving a global energy price shock. Energy prices looked to remain elevated for some years and global emissions had increased via coal and oil substitution for gas. High energy prices via constrained supply are a blunt and socially brutal way to reduce demand and tend ultimately to lead to increased global supply. Thus, the energy price shock highlights limitations in focusing disproportionately on supply rather than demand reduction. Demand uncertainty is intrinsic to climate models, for example the IPCC’s 1.5°C warming models encompass almost an order of magnitude variation in 2050 fossil fuel demand, bracketing the International Energy Authority (IEA’s) net zero scenario. The uncertain pace of demand reduction and of renewables expansion highlight that oil and gas supply reduction is not a shortcut to net zero.

The unfolding tragedy in Ukraine, with loss of trust in the Russians as energy suppliers, have re-calibrated the urgency and need for energy market change. There was already a pressing need to accelerate renewable energy deployment and to prioritise demand reduction, as laid out in the IEA’s net zero scenario. In parallel the upstream industry needed to increase the climate resilience of hydrocarbon supply. With high energy prices set to become the new normal, energy affordability and security have become paramount global issues and should give politicians an imperative to drive demand reduction and set policies to decarbonise energy supply.

The North Sea Transition Deal and Decarbonisation

The drive to increase upstream climate resilience and accelerate national decarbonisation were crystallised in 2021 via the NSTA’s revised strategy and the North Sea Transition Deal (NSTD). Together these constitute a sea-change for the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS), imposing a net zero central obligation and a measurable pathway to net zero absolute emissions by 2050. This high level of UK ambition contrasts with the absence of even a national, let alone industry level, net zero commitment in most of the countries analysed in the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2021 Production Gap Report. This increasing environmental, social and governance differentiation of the UK upstream industry is also evident in NSTA, industry and government initiatives towards increased scope and clarity of climate-related financial and environmental reporting.

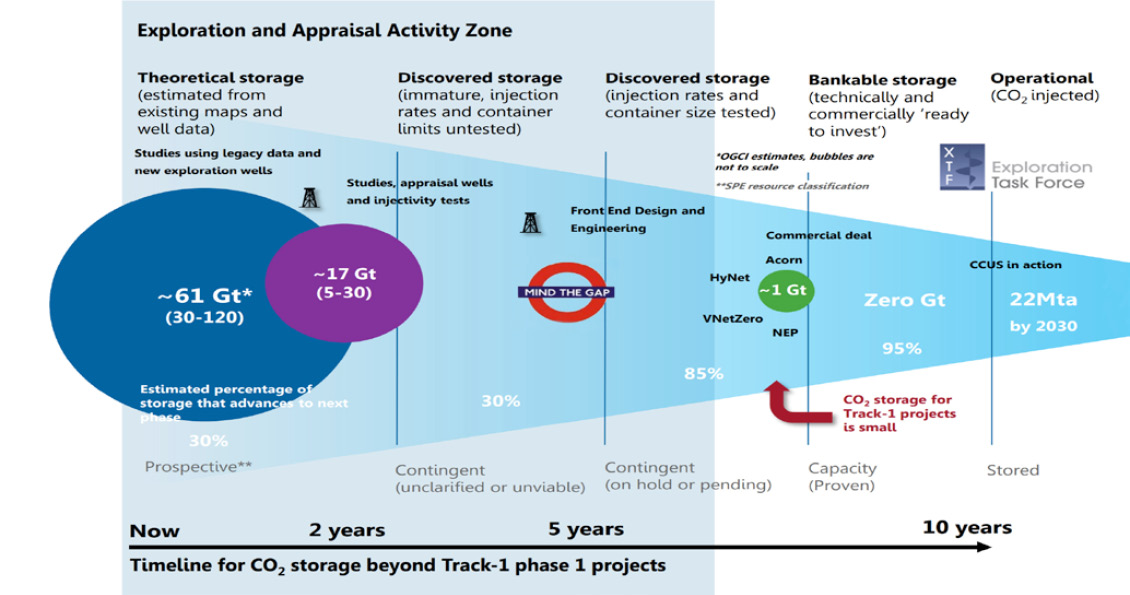

The NSTD additionally provided for a resurrection of carbon capture and storage (CCS), with early ‘Track 1’ projects now identified. The UK‘s potentially world-class geological CO2 storage resource has capacity that could meet hundreds of years of UK CO2 storage demand and provide storage to those neighbouring countries with less favourable geology. This emerging decarbonisation technology, enabled by UK upstream skills and technology, represents a significant opportunity for industry and investors to realise material new revenue streams in support of UK decarbonisation.

Hydrocarbon Supply, Demand and Emissions

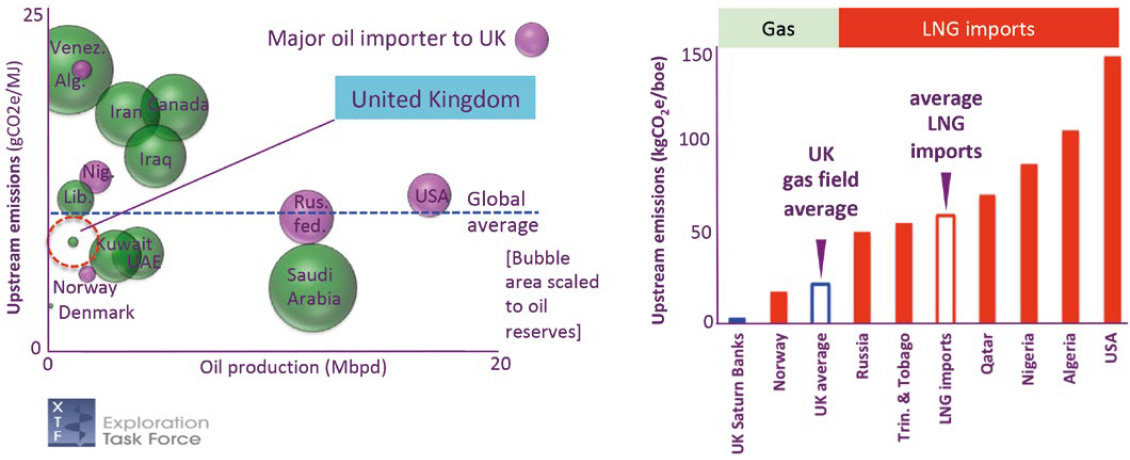

The emissions intensities of UK oil and gas production are respectively more than 20% and 60% below those of global oil production and UK imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) (Figure 1). The NSTD’s targeted 50% reduction in absolute emissions by 2030 will be achieved via production decline, methane reduction per the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, the elimination of routine flaring and up to £3 billion of expenditure on offshore electrification. Electrification can play a major role if economic, regulatory and cultural impediments can be overcome. With growing global demand for and reliance on LNG, the UK’s indigenous, lower emissions gas and Norwegian imports are key to limiting the global emissions impact of UK fossil fuel demand over the next several decades.

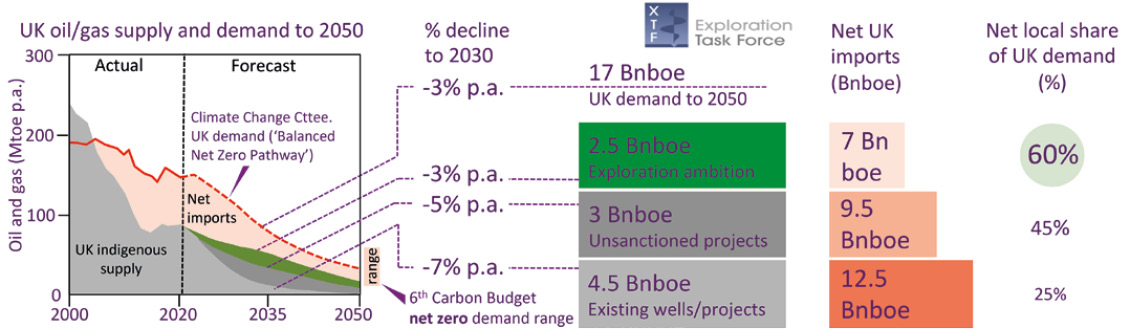

The UK is one of only two UNEP-surveyed countries projecting falling near-term hydrocarbon production. Existing reserves can meet 25% of demand to 2050 – estimated at 17 Bboe in the central scenario of the UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) (Figure 2). New exploration and the development of unsanctioned fields in line with the lower emissions regime could lift the net local share to perhaps 60%, limiting net imports to around 7 Bboe. This is not a ‘ramping-up’ of production, simply a slowing of decline, to around the 3–4% global reduction rates UNEP called for in 2021.

It is often argued that new oil and gas development will lead to economic stranding of assets during the energy transition. This risk is mitigated in the UK by measured fiscal terms, gas market undersupply and the lower emissions intensity of many fields. UK gas production now meets less than 50% of UK demand. Imported LNG meets around 20% of demand but its high emissions intensity makes it responsible for some 44% of upstream (i.e., Scope 1 and 2) global emissions associated with UK gas consumption. Despite undersupply, E and A activity in the Southern North Sea (SNS) is at historic lows. Yet new SNS gas – using existing infrastructure – has exceptionally low emissions intensities, as exemplified by IOG’s Saturn Banks project (Figure 1).

Around 80% of UK oil is exported. UK oil imports are driven by commercial considerations and the crude requirements of a refinery/downstream complex that exports 40% of its output, particularly as petrol. These factors bias towards higher emissions oil imports from countries less committed to emissions reduction (Figure 1). Consequently, the CCC has called for carbon border tariffs or minimum import standards to reduce the global emissions impact of UK fossil fuel demand. Such measures to reduce the UK’s ‘offshoring’ of emissions would reduce imports, support UK upstream emissions reduction efforts and promote emissions intensity as a differentiator in global hydrocarbon markets.

The Role of Carbon Capture and Storage

The UK’s substantial geological carbon storage resource is estimated at 78 billion tonnes (mid case) of theoretical offshore capacity. CCS is critical to the UK meeting its binding commitment to net zero by 2050. It is key to reducing industrial emissions and to decarbonising gas-fired power generation, in addition to facilitating blue hydrogen production (i.e., hydrogen made from natural gas with stored CO2 emissions). The CCC’s 6th UK Carbon Budget calls for up to 180 Mt p.a. of CO2 storage by 2050, with the Government’s Net Zero Strategy setting an ambition to achieve 50 Mt p.a. by 2035.

The UKCS subsurface is well calibrated by petroleum industry data, but none of the theoretical storage capacity is proven storage underpinned by commercial agreements (Figure 3) and the proportion of theoretical storage resource which can achieve proven (or bankable) status remains uncertain. To remain consistent with the targets set in the 6th Carbon Budget, this emerging sector needs E and A seismic and drilling to mature sufficient resource. The UK government is actively developing its CCS deployment strategy, business models, regulatory framework and financial support packages to underpin the development of the sector. Success will need a fiscal regime that facilitates risked investment in storage E and A and which can carry the inevitable E and A failures that will accompany the maturation of theoretical resource to assured operational storage.

The Low Carbon Re-invention of the UKCS

The technical and economic basis for some claimed roles of blue and green (electrolytic) hydrogen needs further analysis and development. But hydrogen will undoubtedly play a role with CCS in driving the re-invention of the UKCS as an integrated energy supply and carbon storage basin, utilising existing infrastructure to reduce costs. The NSTA asserts that the UKCS could meet up to 60% of required UK net zero abatement through CCS, hydrogen, offshore renewables and their close integration with lower carbon oil and gas facilities. In this context, exploration can play a key role by prolonging lower emissions oil and gas supply, under a climate compatibility checkpoint process that validates the case for responsible exploration investment. Successful exploration can minimise the global emissions impact of UK demand, limit imports, support the challenging economics of offshore electrification, underpin blue hydrogen and extend infrastructure life. Additionally, the retention of subsurface knowledge and critical skills is essential to both the growth and long-term containment assurance of CO2 storage.

The NSTD’s high ambition leans heavily on UK upstream expertise, technology and capital to contribute substantially to national decarbonisation. Close integration of lower emissions indigenous oil and gas with emerging low carbon technologies and offshore renewables can accelerate decarbonisation, underlining the extent to which the upstream industry is an integral part of the UK’s carbon reduction trajectory.