From the Archive.

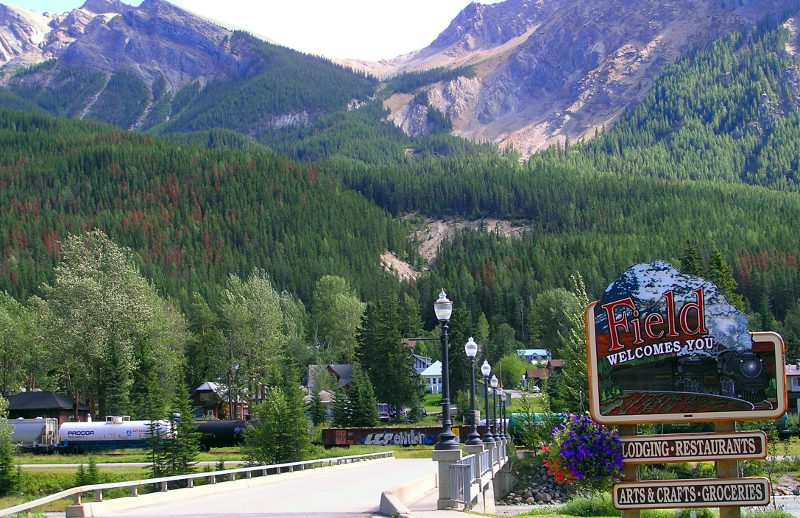

Field, British Columbia is the closest town to the Walcott quarry. Shaded areas are Canadian national parks. (Source: Parks Canada)This article from 2009 was missing from our archive so we uploaded an updated version. We liked it so much we thought you might enjoy the chance to read it, for the first time, online.

Field, British Columbia is the closest town to the Walcott quarry. Shaded areas are Canadian national parks. (Source: Parks Canada)This article from 2009 was missing from our archive so we uploaded an updated version. We liked it so much we thought you might enjoy the chance to read it, for the first time, online.

The Middle Cambrian world (505 million years ago) was dominated by several large, barren landmasses and one ocean. At that time, the site of the Walcott quarry was located at the edge of a continental platform about 400 km from land. This shallow, tropical sea bordering the ancestral continent of North America, called Laurentia, was teaming with a diverse variety of soft-bodied animals, maybe as diverse as we have today.

Many details of their external morphologies would be preserved in the mud at the base of an ancient submarine cliff adjacent to the site. The mudrock and its contained fossils then would ride on this continent for eons, eventually to be forced upward by continental collisions that created the Rocky Mountains much later during the Mesozoic Era. Finally, wind, water, and glaciers would carve the spectacular landscape we see today and expose this most famous Cambrian fossil bed.

A Rewarding Hike

Field, British Columbia. (Source: T. Smith)Late summer in 2008, after a short orientation at the base of Takakkaw Falls outside Field, B.C., a group of 20 like-minded, but quite diverse, people from all over the world started the 20 km hike to the Burgess Shale locality in the cool morning shade. Quickly gaining elevation and anticipation, views of the waterfalls and surrounding mountains became breathtaking. The scenes constantly changed through the day as the excitement mounted with every step.

Field, British Columbia. (Source: T. Smith)Late summer in 2008, after a short orientation at the base of Takakkaw Falls outside Field, B.C., a group of 20 like-minded, but quite diverse, people from all over the world started the 20 km hike to the Burgess Shale locality in the cool morning shade. Quickly gaining elevation and anticipation, views of the waterfalls and surrounding mountains became breathtaking. The scenes constantly changed through the day as the excitement mounted with every step.

At several stops along the trail and at the quarry site, tour guide, Marshall Netherwood from Calgary, explains mountain building, climatology, and general geology of the area using excellent printed visual aids. I am totally consumed by the vastness and pristine beauty of the area. Our lunch stop before reaching the quarry looks out over blue-green Emerald Lake and across to the President Range. Still, the quarry lies ahead. Our second to last stop is where Charles Walcott found the first slabs of rock that eventually led him to the rich fossil beds that lie upslope.

Everyone is excited as the quarry was only a short distance above us. Finally, we arrive and are standing on one of the world’s most famous fossil beds located in some of the most beautiful scenery on the planet. It is of little wonder why Walcott and his family toiled here 19 summers until just two years before his death.

The Discovery

C. D. Walcott at the quarry. (Courtesy of Erin Younger)Charles Doolittle Walcott, former Director of the U.S. Geological Survey and then head of the Smithsonian Institution, started field work high in the Canadian Rockies in 1907. He had become an expert on Cambrian trilobites and found a calling in western Canada. Near the end of his second Canadian Rockies field season in 1909, a slab of rock was discovered along a trail that contained excellently preserved soft-bodied fauna not known anywhere else at the time. Walcott noted that on August 30, they “found a remarkable group of Phyllopod Crustaceans” and “took a large number of fine specimens to camp.” He illustrated these first fossil finds on August 31 of that same year.

C. D. Walcott at the quarry. (Courtesy of Erin Younger)Charles Doolittle Walcott, former Director of the U.S. Geological Survey and then head of the Smithsonian Institution, started field work high in the Canadian Rockies in 1907. He had become an expert on Cambrian trilobites and found a calling in western Canada. Near the end of his second Canadian Rockies field season in 1909, a slab of rock was discovered along a trail that contained excellently preserved soft-bodied fauna not known anywhere else at the time. Walcott noted that on August 30, they “found a remarkable group of Phyllopod Crustaceans” and “took a large number of fine specimens to camp.” He illustrated these first fossil finds on August 31 of that same year.

His party remained on Fossil Ridge for at least another week that field season. On September 1, Walcott and his son worked upslope and “found a fine group of sponges on slope (in situ).” The Phyllopod Bed, a 2.3 m informal unit of shale layers containing a ‘mother lode’ of well preserved fossils, was discovered the following year in 1910.

Being situated in the Middle Cambrian Period, just after the explosion of animals on Earth, gives this quarry even greater significance. The Burgess Shale records at least the same number of anatomical designs we know today and for 75 years remained the best place to see what a Cambrian marine community looked like.

The Walcott Quarry

Walcott was the first to excavate this area in 1910 and quarried until 1917. He returned to the site in 1919, 1921, and 1924 to collect talus material. They excavated with hammers, chisels, long iron bars, and small explosives primarily along the Phyllopod Bed. Walcott did field work in the area until 1925, two years before his death. With limited man power and a short field season, the quarry remained quite small but very productive. In spite of its remote location, Walcott sent over 65,000 specimens on 30,000 slabs back to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The Geological Survey of Canada began collecting specimens from the Phyllopod Bed in 1966-1967. Harry Whittington (Harvard and Cambridge), a leading British paleontologist known for his work on trilobites, led these collecting efforts and rekindled an interest in the study of these very unusual fossils.

Between 1993 and 2000, the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), under the direction of Dr. Desmond Collins, was able to collect over 100,000 fossils from this same locality.

The Fossils and Their Significance

While Walcott was an amazing and prolific collector, his administrative duties in D.C. gave him little time to study in detail the fossils he had found high in the Canadian Rockies. When he discovered the site, he was Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a member of many influential societies. He still found time to photograph and describe most of the fauna in six monographs on the subject that Walcott considered preliminary but still remain the only reference for many taxa.

Walcott viewed the Burgess organisms as members of groups of animals still known today. The general consensus of paleontologists was that fossils can be placed into a limited number of groups with life generally increasing in complexity and diversity over time. Operating on the theory that Burgess Shale organisms had to be ancestral, Walcott placed each species he described into a known class within modern groups.

The Revision

Furthering the work of Walcott and seeking to explain their existence, Paleontologist Harry Whittington was at first bound by the concept of previous studies – that these fossils being old must be primitive forms of later groups. He started with Marrella and published his first monograph in 1971. This was just the beginning of many years of work by Dr. Whittington and two students in particular, Simon Conway Morris and Derek Briggs, on the faunas that inhabited the Cambrian seas 505 million years ago. Their investigation would lead to an almost complete revision of Walcott’s work.

With continuing systematic studies of the oddities, Whittington, Morris, and Briggs grew more and more suspicious that quite a few of the bizarre animals of the Burgess Shale fauna did not fit easily into known categories. The real breakthrough came in Whittington’s third monograph in 1975 of Opabinia. With only 10 known specimens at the time (nine of which were found by Walcott) this 5 cm long odd invertebrate with five eyes, frontal nozzle, and gills above lateral flaps could not be placed within any formal classification; for Whittington, it simply belonged to no known group of animals that have ever lived on earth. Like Opabinia, Odontogriphus, and Hallucigenia, many other apparent oddities were often labeled in collections as being of “problematic” affinities.

Current Research

The diversity of animal forms in the Cambrian is perhaps not as extensive as what author, evolutionary biologist and Harvard University professor Stephen Jay Gould predicted 20 years ago in his book, Wonderful Life. Research today has moved from focusing on bizarre features (for example the nozzle of Opabinia) to recognizing shared derived characteristics, in other words, characteristics that were acquired from a common ancestor.

Many of the “problematic” fossils are now firmly recognized to fit at the base of modern phyla, or to belong to deeper branches in the tree of animal life. For example, Odontogriphus is now firmly recognized to represent a primitive mollusk with no shell. Opabinia is recognized as an early member on the lineage leading to modern arthropods. Hallucigenia is now related to the phylum Onychophora or velvet worms. The list of truly “bizarre” animals continues to shrink every day thanks to new discoveries and new research methodologies.

Trilobites peer out of the quarry toward blue-green Emerald Lake that rests in the basin below Fossil Ridge. (Source: T. Smith)The vast collections from the ROM are playing an important role in this new phase of understanding of the famed biota. The problematic status of many fossils was based on the fact that they were too poorly known with often one or two specimens used for the initial description. A much larger number of specimens are needed to better understand the morphology and evolutionary relationship of these animals. In addition, various degrees of decay has altered features in many specimens but such preservational biases, even subtle, cannot be detected without a large collection of specimens.

Trilobites peer out of the quarry toward blue-green Emerald Lake that rests in the basin below Fossil Ridge. (Source: T. Smith)The vast collections from the ROM are playing an important role in this new phase of understanding of the famed biota. The problematic status of many fossils was based on the fact that they were too poorly known with often one or two specimens used for the initial description. A much larger number of specimens are needed to better understand the morphology and evolutionary relationship of these animals. In addition, various degrees of decay has altered features in many specimens but such preservational biases, even subtle, cannot be detected without a large collection of specimens.

New discoveries in the vicinity of the Burgess Shale as well as in new sites, in particular in China, have not only contributed to more specimens, but also more species to compare with existing species, thus allowing the use of modern phylogenetic methods such as cladistics. Cladistics is a method that seeks to reconstruct the common ancestry relationship between taxa based on shared derived characteristics. The use of modern analytical tools like Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (or EDX) provides elemental analysis of the chemical composition of fossils and has improved our knowledge of how fossils are preserved.

Today, scientists recognize that the Burgess Shale biota is not limited to the original site on Fossil Ridge. Burgess Shale-type fossils have been found worldwide in similar environments dating from the Early and to the Middle Cambrian, and all these deposits follow a more or less common mode of preservation. In other words, the Burgess Shale biota was not unique and was part of a marine community with global distribution during the Cambrian. Since 1981, the ROM has discovered more than 12 sites in the Canadian Rockies alone.

Rerunning the “Tape of Life”

Furthering the significance of this fossil discovery, Gould’s Wonderful Life, uses the work of Whittington, Morris and Briggs to present his ideas. He claimed that during the Cambrian explosion, a multitude of animal designs proliferated and subsequently were eliminated through competition and chance extinctions.

For Gould, the “problematic” animals were evidence of maximum diversity of body plans (or disparity) during the Cambrian period; these animals actually represented new phyla. He claimed that “replaying life’s tape” may not have repeatable and predictable results. Particularly, the fate of our own group would have been left to the survival of Pikaia (an early chordate, thought to be ancestor for the vertebrate lineage, including man) which was also found in the Burgess Shale.

Conversely, more recent findings published by Morris dispute Gould’s conclusions and argue that the body designs we see in the fossils are predetermined by their environments and rerunning life’s tape would give similar results each time. In this debate, Morris concluded: “Contingency or no, I believe that a creature with intelligence and self-awareness on a level with our own would surely have evolved….”

Research on this and other important Middle Cambrian fossil localities continues, adding to our understanding of the origins and evolution of life on Planet Earth.