There is an established notion that political geography is a sociogeographic science, which studies territorial differentiation through political phenomena and processes and which expresses the policies of states with respect to its borders and its interaction with other countries, primarily neighbouring ones. In recent years, one can see the appearance of a similar notion of political geology, particularly in the Arctic, where the science has become a tool for the justification and protection of political interests of states and the expansion of their borders, while taking no account of the geological processes themselves or their objective interpretation.

In this article we see, through the example of the Arctic, how geology is being transformed from an assemblage of sciences into a powerful tool for the rearrangement of maritime borders of states, often to the prejudice of the actual science.

Why the Arctic?

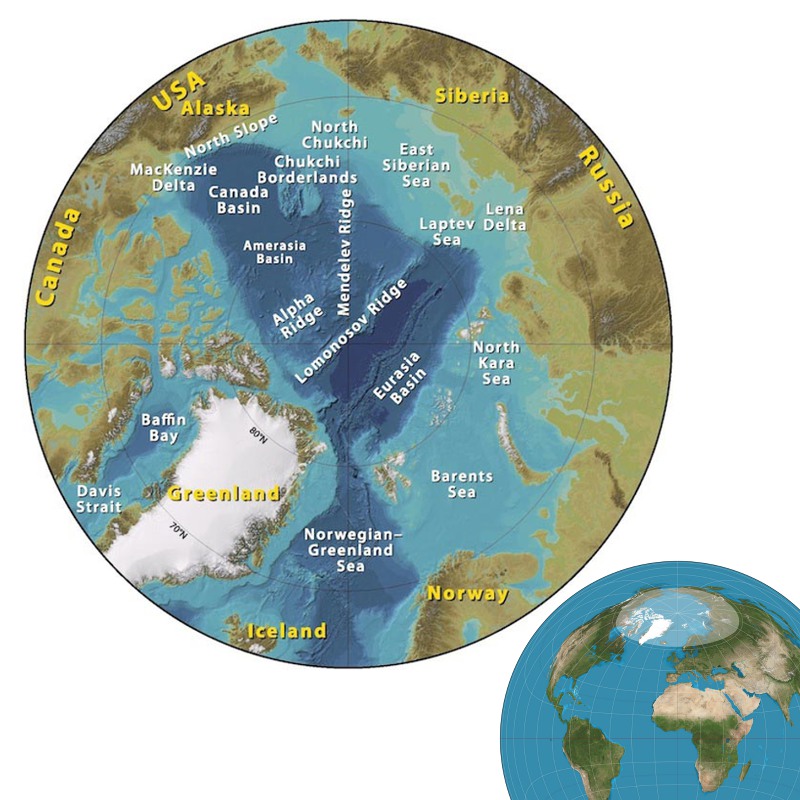

Arctic Cirlce map (Jakobsson et al, 2008) and inset with ‘Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection’ with Arctic circle (approx. 66.5 degrees north of the equator) highlighted (Source: Strebe).The Arctic region was tinged with heroism in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Polar explorers were viewed as heroes overcoming unheard of icy dangers in a continuous chain of acts of bravery – although not many people understood what these polar explorers were engaged in and why they ventured their lives, except perhaps to demonstrate the limitless capabilities of the human organism. Thereafter, the Arctic was forgotten, left to a few people interested in such extreme environments, because there was nothing there of interest to the ordinary man.

Arctic Cirlce map (Jakobsson et al, 2008) and inset with ‘Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection’ with Arctic circle (approx. 66.5 degrees north of the equator) highlighted (Source: Strebe).The Arctic region was tinged with heroism in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Polar explorers were viewed as heroes overcoming unheard of icy dangers in a continuous chain of acts of bravery – although not many people understood what these polar explorers were engaged in and why they ventured their lives, except perhaps to demonstrate the limitless capabilities of the human organism. Thereafter, the Arctic was forgotten, left to a few people interested in such extreme environments, because there was nothing there of interest to the ordinary man.

But public and media interest in the Arctic is growing annually, partly fuelled by an awareness of the area’s vast resources. The US Geological Survey estimates the Arctic could contain 1,670 Tcf of natural gas and 90 Bbo, or 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas and 13% of its oil, plus deposits of precious and rare earth metals and massive fishery resources.

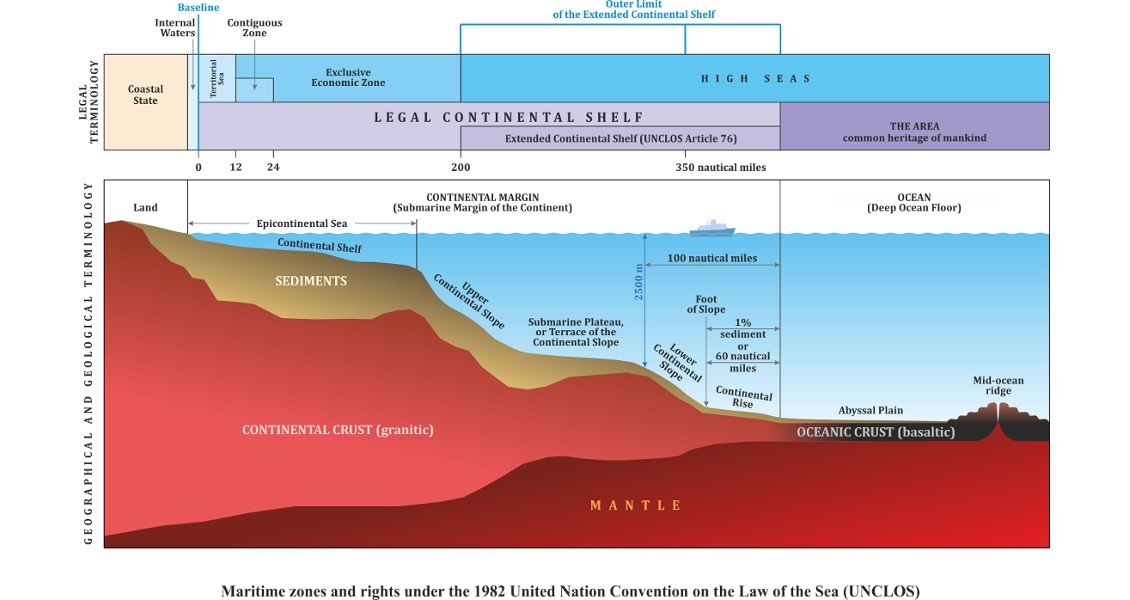

According to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982 (UNCLOS), the circum-arctic states have the right to develop the mineral resources of the continental shelf which is a continuation of their territories within their respective exclusive economic zones. However, no oil or gas company would consider implementing a project until all legal or political risks are settled as the financial risk is too high.

The continental shelf is a term that refers to the ledges protruding from the continental land mass into the ocean. They are covered with relatively shallow water (approximately 150–200m), eventually passing into the ocean depths. Continental shelves occupy around 8% of the total area of ocean water, forming the extended boundaries of every continent and coastal plain. They were part of the continental land mass during glacial periods and are inundated during interglacial periods.

A Spectrum of National Interests

When referring to the huge resource potential of the Arctic, most experts consider that 97% of all known and potential natural resources in the Arctic are situated in the zone of sovereign rights and jurisdiction of the Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and USA). However, few point out that this huge percentage is all found in the marginal seas of the Arctic Ocean, within the 200-mile economic zone. What lies beyond?

The Arctic comprises two main basins. The Paleogene Eurasian Basin consists of oceanic crust with about a kilometre of sedimentary cover, lying in 4–4.5 km water depths with extremely harsh ice conditions, making it both logistically and economically challenging. The Amerasian Basin is considered more promising; it comprises Cretaceous continental sediments that were subjected to strong extension as the Eurasian and the Canada Basins opened. Sedimentary cover varies between 1 km and 2 km, but with water depths up to 3 km and harsh ice conditions, it also offers challenges to exploration.

But what has geology to do in such an intricate tangle of political interests of countries? The delimitation of maritime boundaries in the Arctic must be officially solved at the international level. States must file an application to establish the outer limit of their continental shelf; then get positive recommendations from the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf; define and agree principles of delimitation of maritime borders within the boundaries of each country’s continental shelf; before finally signing interstate agreements on the delimitation of their maritime borders.

However, before any of that can be done, a geological substantiation of the continental shelf will have to be prepared, because that is at the root of outlining the limits of each state’s continental shelf – coupled with the wish of each country to maximise its continental shelf in its national interest.

Establishing the Limits

So how is the limit of the continental shelf beyond the 200-mile zone established?

Under the Convention, submarine elevations and ridges can be attributed to the continental margin and hence to the ‘juridical continental shelf’ if their continental origin and association to natural components of the underwater continental margin are proved. It stipulates that the continental margin does not include ‘the deep ocean floor with its oceanic ridges or the subsoil thereof’, a provision specially envisaged so as to exclude the possibility of including the mid-oceanic ridges in continental margins.

UNCLOS contains a number of formulae and limiting lines by which the edge of the continental margin shall be determined based on bathymetric and geological criteria. The former include the position of the foot of the continental slope, while the geological criteria include data on the structure and thickness of the sedimentary cover, the nature of the earth’s crust and geological and geophysical evidences of the position of the continental rise. If no data on the sedimentary cover is available, the limit of the shelf may be delineated by straight lines not exceeding 60 nm (nautical miles) in length, drawn from the foot of the continental shelf (FCS). According to the Convention, a coastal state can use a combination of limiting and formula construction lines to increase the size of its continental shelf.

Article 76 of the Convention outlines limits beyond which the continental margin determined by these criteria cannot extend: either 350 nm from the coast, or 100 nm from the 2,500m isobath. For submarine ridges, only the 350 nm limit is applicable, with the exception of submarine elevations that are natural components of the continental margin.

Different Interpretations

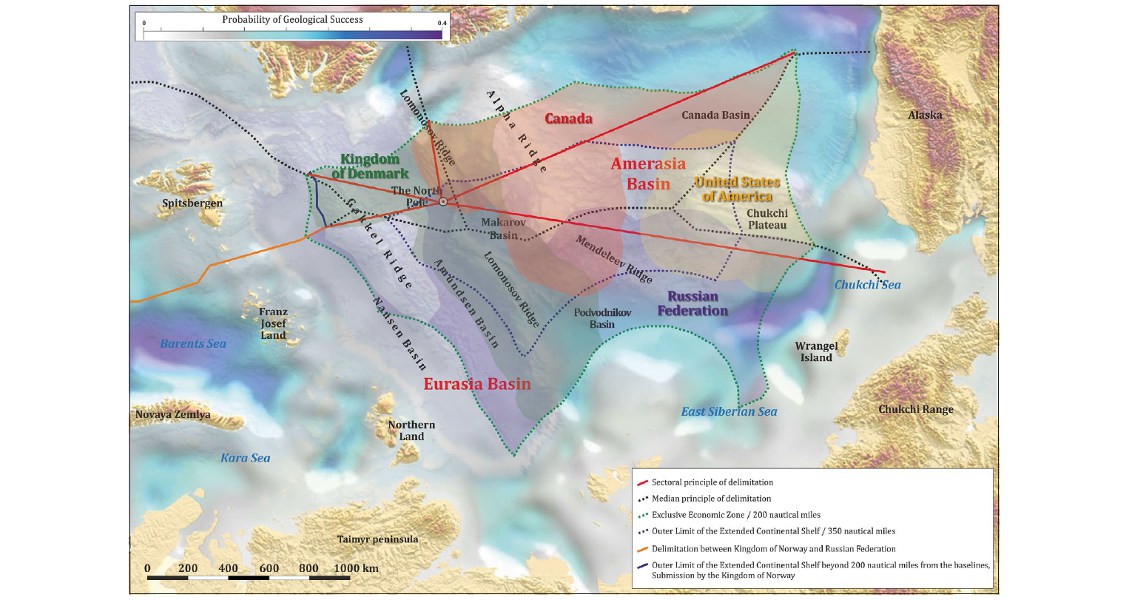

So what do the limits of the continental shelf look like from the viewpoint of the different countries?

In December 2014, Denmark filed its application for establishing the outer limit of the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean. When determining the limit of the shelf, it included in its continental shelf the Lomonosov Ridge, interpreting it as an integral part of the northern continental margin of Greenland both morphologically and geologically; the Podvodnikov Basin, limited by the 2,500m isobath and 100 nm from the Lomonosov Ridge; the Amundsen Basin, along the FCS + 60 nm formula line; and part of the mid-oceanic Gakkel Ridge, applying the 350 nm distance limit, classifying it as a submarine ridge, thus creating a precedent for the inclusion of oceanic ridges in claims.

Canada’s continental shelf, in accordance with Article 76 of the Convention, may include part of the Canada Basin up to the 350 nm limiting line, depending on the thickness of the sedimentary cover, thereby emphasising the importance of geology; the Alpha Ridge, which is classified as a natural continuation of the continental shelf of Canada; and part of the Canada Basin and of the Podvodnikov Basin along the limiting line of 2,500m + 100 nm from the Alpha Ridge.

The continental shelf of the Russian Federation may include the Lomonosov Ridge and the Podvodnikov Basin, as natural continuations of the continental margin of Eurasia, following morphological and geological criteria; the Mendeleev Rise, the Chukchi Basin and the Chukchi Plateau, using the same criteria as they were formed by extension of the earth’s crust and volcanic activity in the course of formation of the Amerasian Basin; and parts of the Amundsen and Nansen Basins along formula lines depending on thickness of the sedimentary cover.

A possible limit of the USA’s continental shelf may include the Chukchi Plateau, by morphological and geological criteria, as a natural continuation of the continental shelf of Alaska, again resulting from geological activity during the formation of the Amerasian Basin; and part of the Canada and Podvodnikov Basins along the limiting line of 2,500m + 100 nm from the Chukchi Plateau.

What do we understand from this? As can be seen from the map above, a serious overlap exists in the interpretation by the countries of their continental shelves and, as a consequence, there are major disagreements in interpretations of the geological history of the evolution of the Arctic. Everything should depend on geological evidence and reasonableness – but as has often been said, “two geologists always have three absolutely different opinions…” It is worth noting that each of the countries interprets the same geological information to its own favour, often strongly distorting the objective reality.

Delimitating the Continental Shelf

After establishing the outer limit of the continental shelf it is necessary to delimit the continental shelf between countries under Article 83 of the Convention. In the Arctic, several approaches have historically been used.

One of these is the concept of the sectoral principle of delimitation of the Arctic territories among the five circumpolar states, which was worked out in the early 20th century in order to exclude the ice-covered areas of the Arctic Ocean from the then rules of the international law. Applying this principle to the sea floor of the Arctic Basin requires the agreement and unified position of all five states, but unofficial monitoring conducted in the 1990s showed that they prefer to establish the outer limit of the continental shelf in the Arctic using UNCLOS.

Norway, for example, which ratified UNCLOS in 1996, filed its application for establishing the outer limit of the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean in 2002, having excluded the Gakkel Ridge. Denmark does not recognise the sectoral principle, advocating delimitation of the shelf along the median line – giving it ownership of the North Pole. In its application to determine the limits of the continental shelf, it included the Lomonosov Ridge, the Podvodnikov Basin and part of the Amundsen and Nansen Basins, up to Russia’s 200-mile economic zone.

Canada took its first steps in securing its Arctic claim as long ago as 1909, but in 2005 it departed from the sectoral principle when determining its Arctic Ocean shelf by seeking to establish the outer limit of its continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean strictly under Article 76, leaving part of the Canada Basin classed as International Seabed.

The Russian Federation approved the sectoral principle of delimitation back in 1926, declaring that ‘all lands and islands, both discovered and which may be discovered in the future’ were the territory of the USSR. In 2001 it filed its first application, adhering to the sectoral principle, but the Commission was unable to confirm the outer limit of Russia’s continental shelf and recommended the submission of additional bathymetric and geological data.

An alternative concept of delimitation is the principle of ‘the median (equidistant) line’. In the 1950s and ’60s this was the generally accepted method and was included in the Geneva Convention of 1958, but its application did not always satisfy contesting parties. In 1960 the International Court of Justice, considering the continental shelf of the North Sea, noted that the median line method was not a part of customary international law and proposed the principle of equity instead. This departure from using delimitation along the median line as the compulsory method for solving coastal state border issues was confirmed in decisions of the International Court of Justice delimiting the continental shelf between Tunisia and Libya in 1982 and the offshore areas between Canada and USA in 1984, among other examples. The median line as the norm was formally overthrown in UNCLOS in 1982, when the principle of equity was fixed as the best method of identifying the limit of the economic zone and the continental shelf.

Geology Versus Politics

The Arctic now is a spectrum of national interests covering state security, influence on transport routes and economics, making it the crossing point of the geopolitical interests of both Arctic and non-Arctic states.

So how will the relationship between political order and the geological structure of the Arctic change in the next ten years? We will see, and time will tell; but it would be good to find politics taking second place to geology, rather than the present situation where geological considerations are being overshadowed by politics, relinquishing the principles of scientific disciplines.