If you look at the volume of water versus hydrocarbons produced from the Permian Basin per day, the basin would surely qualify as being predominantly a water production exercise: 20 MMbb of water versus 6 MMbb of oil. Every 24 hours.

Of that 20 MMbb, 16 million is currently being re-injected in the subsurface – there is currently no other place for the water, or better, brine, to go. The most economical solution is to dispose of it by drilling injection wells that put it deep underground.

But even though re-injection is the most economical solution, it is not without its drawbacks. Induced seismic events are one of those, in addition to issues related to compromised legacy wells from conventional oil and gas production, that allow re-injected brines or formation waters to flow back to surface and contaminate agricultural land.

And that is where Katie Smye from The University of Texas at Austin comes in. As principal investigator of the Center for Injection and Seismicity Research, she coordinates a major project that is looking at the regional plumbing system in the Permian Basin with the dual aims of understanding how problems related to water injection arise as well as better predicting how long safe injection can go on for.

“There has been a lot of interest in recent years in legacy wells, especially orphaned and abandoned ones,” Katie says. “Most institutions working on those wells are focused on the surface expressions, such as methane or brine leaks, or using technology to find these abandoned wells in the first place. We have always been interested in the subsurface hazard posed by oilfield waste water injection,” she says, “and because injection has become such a large-scale operation in the USA with the advance of unconventional drilling and associated produced water, the urgency to better understand how fluids behave in the subsurface has increased.”

Let’s get some of the definitions out of the way first.

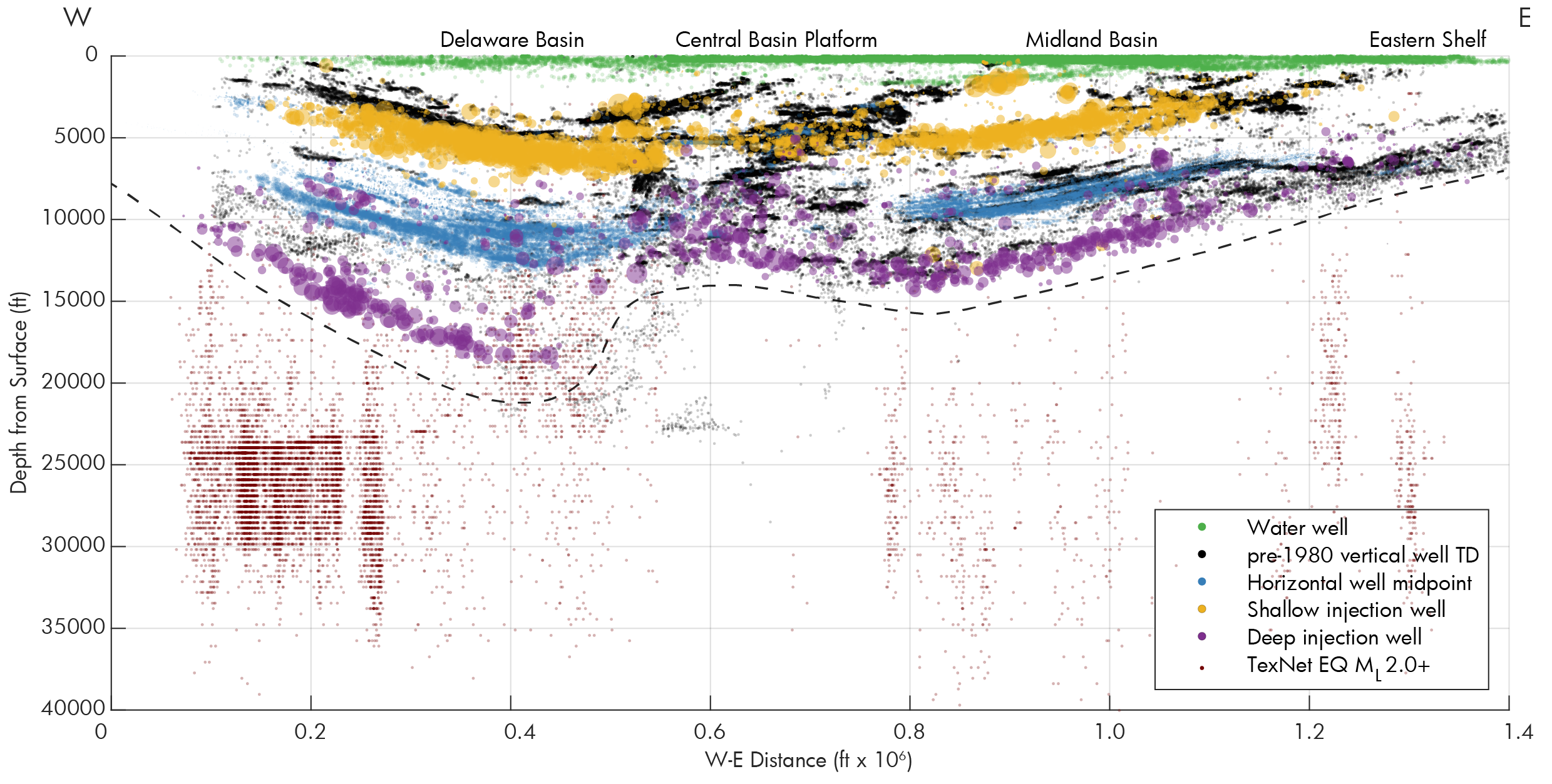

Basically, there are two levels at which water is being reinjected in the Permian Basin: Either stratigraphically above the unconventional reservoirs or beneath them. “These two levels of injection are defined not by depth, but by stratigraphy, as the shales themselves can be found at different depths depending on the location in and structure of the basin,” explains Katie, “but deep injection in this context means beneath the shales, whilst shallow indicates above the shales. Shallow in most cases is still around 6,000 ft deep, well below the aquifers used for drinking water production.”

The history of water injection in the Permian Basin is diverse, and both shallow and deep reservoirs have been used from the start. However, what can be said in very general terms is that deep injection has given way to shallow water injection in recent years, mostly driven by induced seismic activity that has made headlines in a few cases. Most of the seismicity is caused by deep injection, close to more competent basement rocks that are faulted. Another drive towards shallow injection is the lower costs of drilling the injection wells.

Legacy wells

As pointed out by Texans like Sarah Stogner, shallow injection has its drawbacks too, and they relate to a large extent to legacy wells.

“The problem we have inherited in the Permian Basin,” says Katie, “is a vast pool of old wells that were drilled, operated, plugged and abandoned at times of less stringent regulations. The casings of these wells may have degraded over time and are now exposed to increased pressures due to injection.

And where is the waste water being injected? In the high-quality reservoirs from which we first produced conventional oil and gas through all these wells.”

For that reason, many of the reservoirs in which injection now takes place have been artificially connected with the surface through thousands of rusty wells. “It sometimes keeps me awake at night,” says Katie.

“Our data clearly show that for about 90 % of the leaking legacy wells in the Delaware Basin, we see uplift of the ground surface as indicated by satellite data,” explains Katie. “That tells us a lot about what is happening in the subsurface, with pressure ramping up in reservoirs where waste water is being injected to such an extent that it has a measurable effect at surface level. And obviously, it is the increase in pressure that also affects some legacy wells in that brine is finding the path of least resistance through these anthropogenic pathways.”

“What we do as a group in the Center for Injection and Seismicity Research is to better understand the subsurface risk factors that come with waste water injection and suggest ways to mitigate against any unwanted issues,” says Katie.

And that research is badly needed. “When I speak at public events, I often have a number of ranchers lined up afterwards to talk to me about the issues that they are facing on their tracts of land. Operators tend to be concerned about their own acreage, but we try to build a supra-regional model combining all the observations we make and hear about, informed by data provided by those operators.”

How much can be injected?

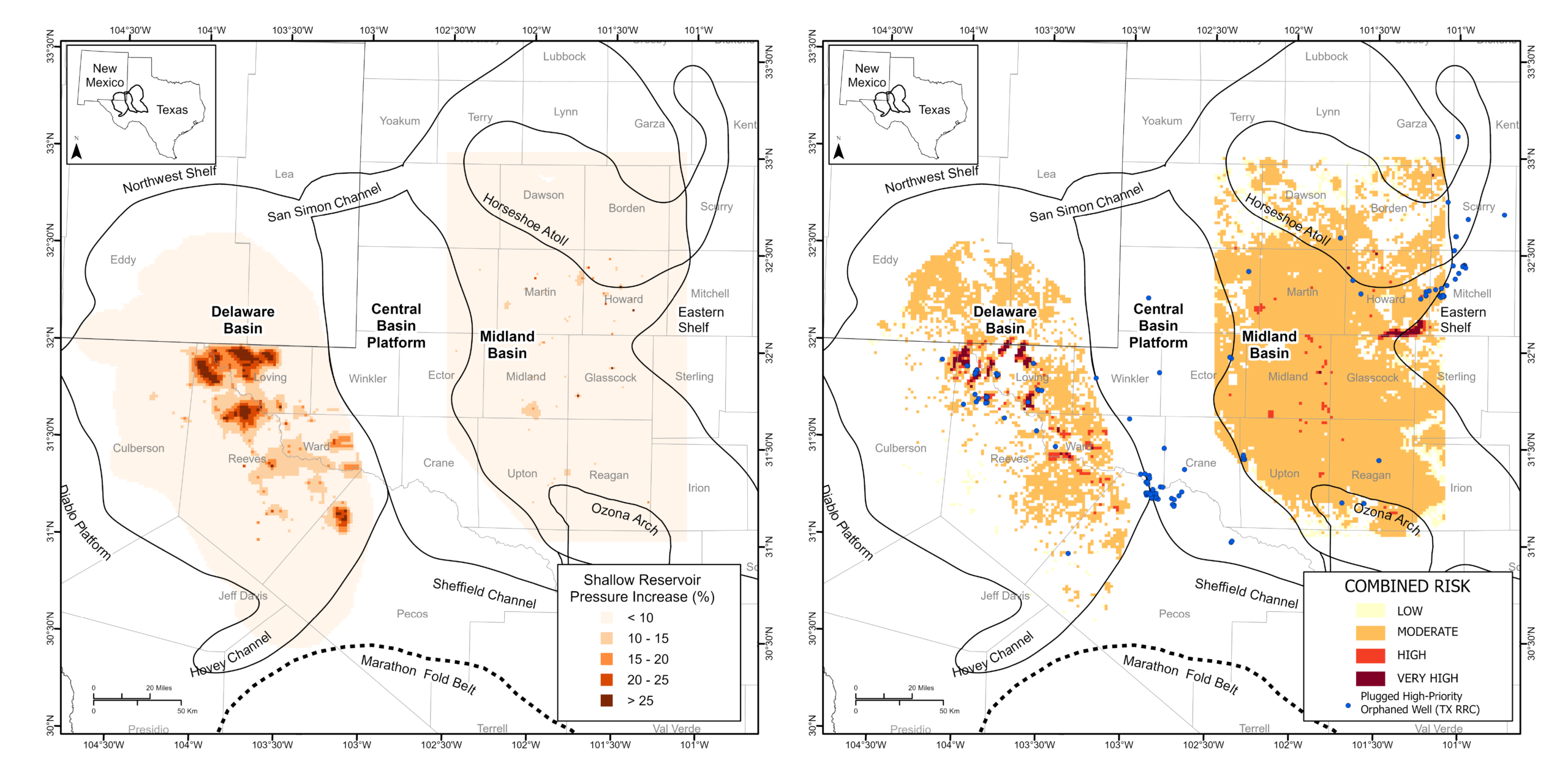

The big thing that Katie and her research consortium are now pushing is the compilation of reservoir injection exceedance maps in order to arrive at a better estimation of what the several reservoir candidates for water disposal can safely host. That is less straightforward than you might think, because it is not only the reservoir properties that have to be taken into account, but also the observations already made when it comes to earthquakes or leakage to surface.

That subsequently opens the question of how to find all the wells that are leaking. “We use all methodologies that are at our disposal,” says Katie. “We monitor the news, we look at temporary flight restrictions, and we also use the public list of high-priority wells that have been identified for state-funded plugging. In addition, we get information from the operators and other stakeholders in West Texas about the issues that they have been dealing with.”

But that is only really the top of the iceberg. “I’m sure that for every well we see leaking at surface, there are a dozen where there is no surface expression. At the same time, these wells still present a risk to subsurface cross-flow,” says Katie. It illustrates the uncertainty that comes with producing the maps, knowing that things like reservoir compressibility, porosity and permeability also play a role.

But no matter the uncertainties involved, Katie and her group have now produced the first series of basinwide injection capacity exceedance maps, providing more context on how much injection capacity remains in reservoirs across the Permian Basin.

TRUCKING WATER ACROSS THE BORDER

Each state has different regulatory frameworks when it comes to water injection. In the New Mexico part of the Delaware Basin of West Texas, which is one of the two major subbasins of the Permian Basin, shallow injection is not frequently permitted as it is thought to harm reservoirs that could be used for mineral extraction. As a result of this ban and the limited capacity of deeper reservoirs in New Mexico, 3 MMbb of water are currently transported across the border to Texas every day, where shallow water injection is allowed.

“The interesting aspect about this situation,” says Katie, “is that sometimes New Mexico’s shallow reservoirs still see the effects of shallow injection across the state line in Texas, whilst earthquakes still occur in the Texas Delaware Basin where deep water injection has stopped since the closure of 20 deep injection wells. It goes to show that geology, fluids and pressure fronts do not follow state boundaries.”

It’s very much an iterative process that needs constant maintenance. “For instance,” Katie explains, “if there is a blowout in an area where the maps did not predict exceedance given the current injection and pressure data and models, we need to bring that injection capacity down.”

“But all in all, I think this work is essential because we look at a basinal scale, combining observations and data from across the entire Permian Basin. And in addition to the outcomes being relevant to the oil and gas producers, this is also relevant to basin-scale carbon storage projects that may face similar issues.”

Communicating science

The analysis has also exposed Katie to the limitations and challenges of communicating science to the public. “If someone picks a square mile on our injection capacity map and sees that his/her tract of land is close to capacity exceedance, it becomes important that we have communicated the uncertainties behind our calculations and the range of possible scenarios. That uncertainty is not always easy to get across,” she says.

Communication is also a very important factor when it comes to working with the industry partners in Katie’s project. “For instance,” she says, “the public often wants a reply from the Center for Injection and Seismicity Research when an earthquake happens. And not next year in a peer-reviewed publication, but today, explained in simple words. That is sometimes a challenge, because we may not always have the right data to draw robust conclusions in a timely manner.”

“For example, we used to rely on injection data that was, in some cases, up to 18 months out of date. Under those circumstances, without knowing recent trends in injection rates and pressures, it was challenging to be certain about the causal agent of an earthquake. That situation has now improved with more stringent data reporting requirements, but the flipside is that we now end up in situations where we receive requests for public comment whilst our industry partners and regulatory agencies may benefit from publication of our work in peer-reviewed scientific journals rather than short-term commentary where uncertainties are difficult to communicate and messaging is out of our control.”

“The best way around this is,” Katie says, “to flag these things and discuss them with our advisory committee of company representatives. Whilst we have autonomy over our methods of communication, it is certainly a new field for us to provide commentary without peer-reviewed scientific backing, and we are much more confident in that effort if we have a broad consensus across our stakeholder group.”

No denial

Regardless of these hurdles that must be jumped at times, Katie sees that many companies are taking a constructive approach towards the problems that arise. “We don’t live in the days of denial of adverse impacts of injection anymore,” she says. “All of our industry partners agree that earthquakes, surface flows, and other injection impacts are unwanted, and that facing the issue is the best way to mitigate them. Sure, companies differ in their approaches to mitigation and speed of response, but overall I’d say there is a willingness to work collectively to solve these challenges such that injection, and therefore production, can be sustained.”