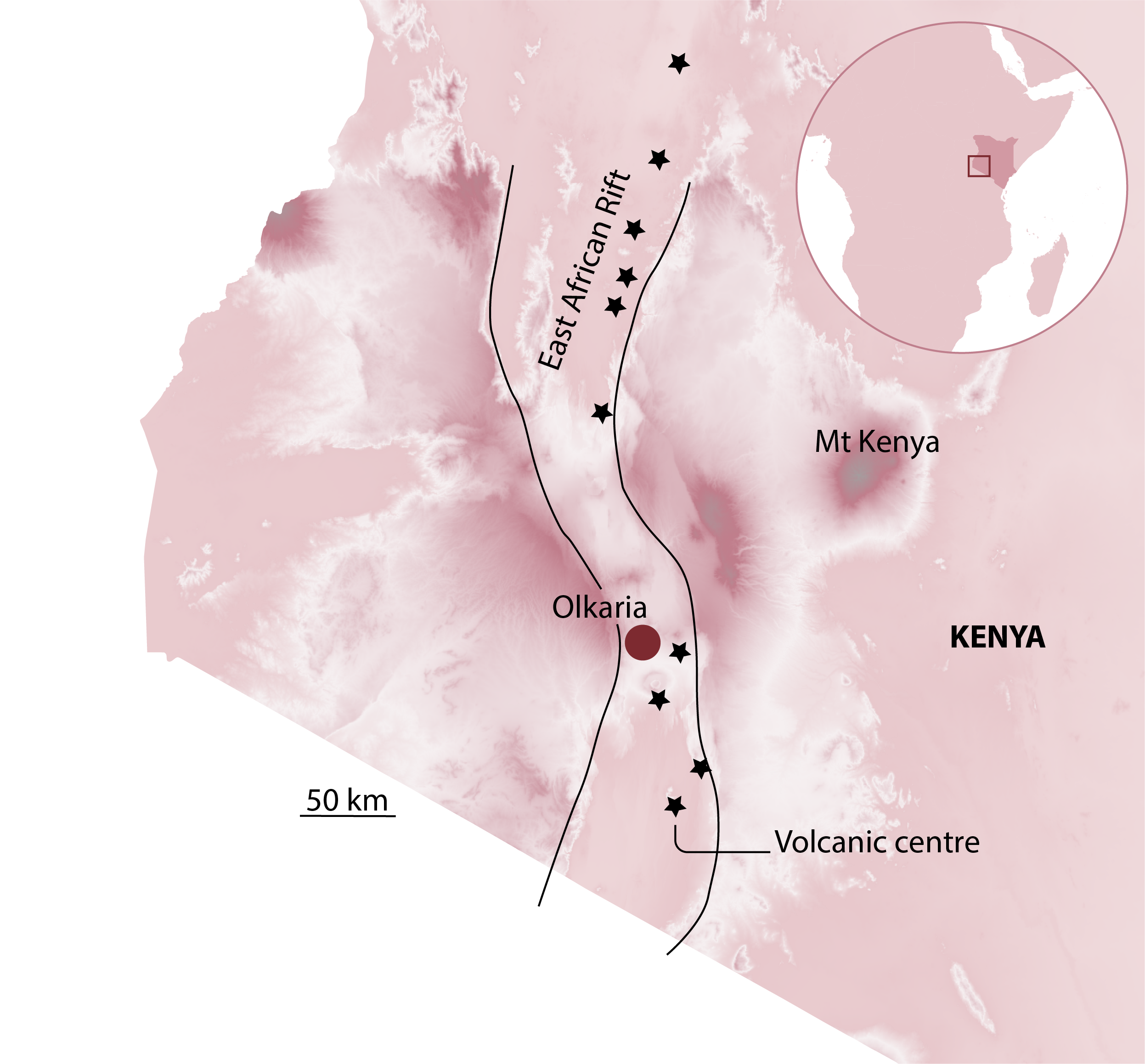

Following the drilling of successful exploration wells into the Kenyan Rift Valley in the 1970’s, the flagship Olkaria geothermal field has seen a steady development to a capacity of around 800 MW today. It is still the main geothermal project in Kenya, supplying around 80% of the geothermal energy produced in the country.

The geologically young East African Rift (EARS) is an ideal location for the development of geothermal projects because of the high subsurface temperatures at relatively shallow depths. At Olkaria, the reservoir from which steam is being produced consists of porous and permeable volcanic rocks – rhyolites, trachytes and basalts – which overly magmatic and intrusive bodies at a greater depth.

Geothermal motor

Fluids flow within the volcanic succession at Olkaria are known to show convective circulation from the base to the top of the reservoir interval. This is what is often referred to as the geothermal motor of the system, transferring heat from closer to where the magmatic bodies are to shallower regions.

As with many volcanic geothermal areas, the reservoir succession at Olkaria is overlain by a claystone that consists of hydrothermally altered minerals. In that sense, the reservoir has a clear upward limit, comparable to oil and gas fields.

Imbalance

Even though the produced steam is re-injected as fluids into the volcanic succession, there is an overall mass imbalance between produced and injected fluids. As a result, there is concern that this could negatively impact fluid circulation patterns on which the production of geothermal energy relies.

In addition, as the development of the geothermal field has now reached a mature stage in the Olkaria field, there is an increasing risk of well interference and drilling of unproductive wells.

For these reasons, it has become more and more important to better characterize the geothermal field and map where future opportunities may exist. This was done using an ambient seismic noise tomography approach by a consortium led by Twente University in the Netherlands. Whilst the results have not yet been published, the shear wave velocity model has resulted in additional insight in the structure of the Olkaria geothermal field.

Mature geothermal fields

In combination with our report on the mature state of geothermal developments in Turkey (see page 62), it does suggest that what the West Anatolia rift system is for Turkey, is the Olkaria field for Kenya: the low-hanging fruit that enabled relatively quick and profitable production of geothermal energy. Whilst there are multiple projects underway in Kenya, it seems that these are not as big or “easy” to produce from as Olkaria.