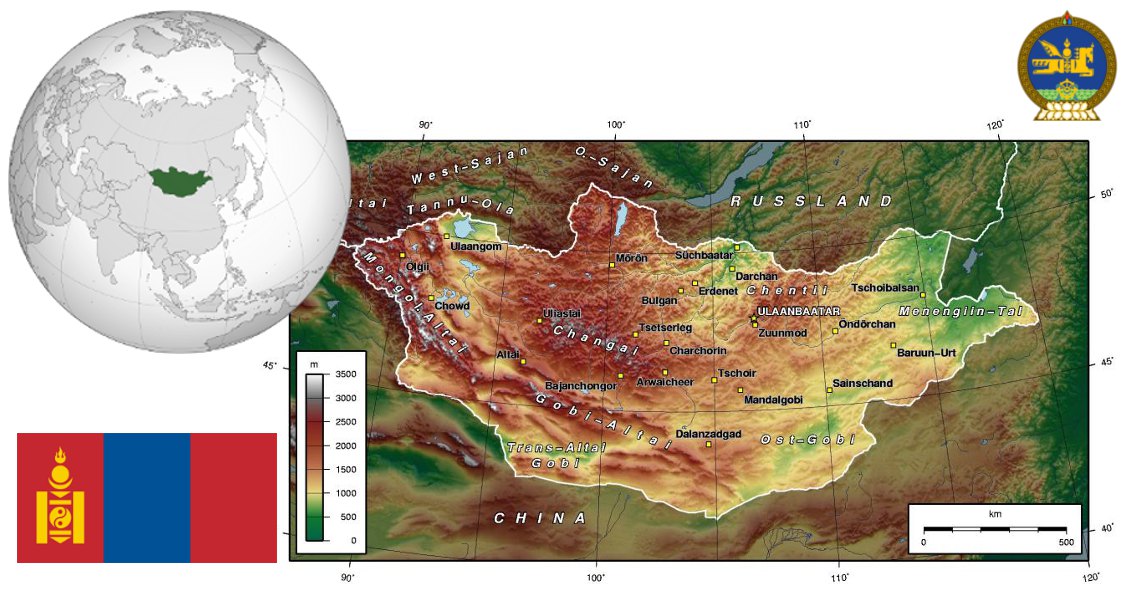

Mongolia emerged as an independent and fledgling democracy following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the intervening two decades the country has made massive progress, with a fast growing economy and a stable political system. Growth is now in double digits, largely due to a rapidly increasing mining sector. The Oyu Tolgoi gold and copper mine, in the South Gobi desert, for example, went on stream last year and will contribute up to 30% of Mongolia’s GDP at its peak. If progress goes to plan, then this mine will be one of the largest copper mines in the world by the end of the decade. Mongolia is also a large producer of coal, supplying the domestic energy market, with the surplus exported to China.

Despite this growth, however, and with an emergent middle class requiring ever more energy, Mongolia still imports 100% of its refined products, mostly from Russia to the north. The domestic market currently requires around 25,000 bopd, with over 50% being utilized by the mining industry. This is a supply problem that will only get worse, so now the time is right for explorers to move in and address the issue.

Mongolia has been producing oil for many decades, but so far only on a small scale. The Tsagaan Els and Zunbayaan fields in the East Gobi were drilled on seeps as long ago as 1941, but have only produced combined volumes of around 10 MMbo, although they are still producing about 1,000 bopd. More recently, China’s PetroChina subsidiary, Daqing Oil, has been producing from the Toson Uul field complex in Blocks XIX and XXI, near Mongolia’s eastern boundary, in the Tamtsag Basin. This is a southerly continuation of China’s producing Hailar Basin trend. The Tamtsag Basin has so far produced about 15 MMbo since it came on stream in the late 1990s. The basin is currently producing about 17,000 bopd from several small fields, with the crude exported south to China’s Hohhot refinery.

So what is the potential for further development of this fledgling industry?

Megasequences and Analogous Basins

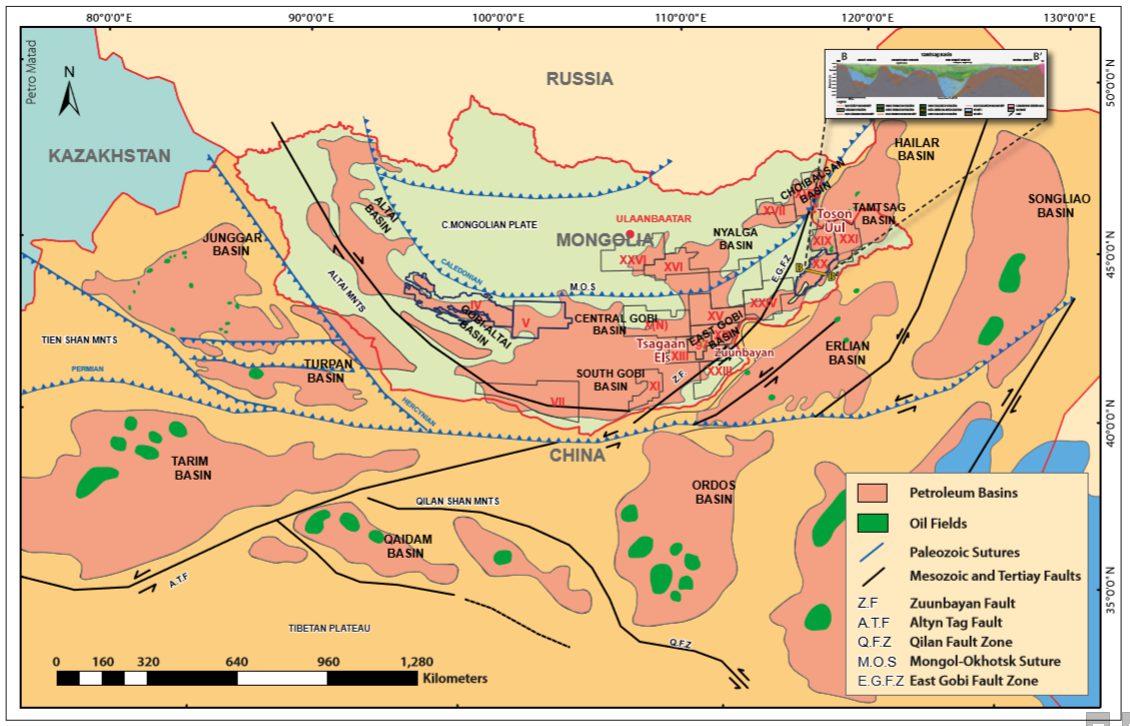

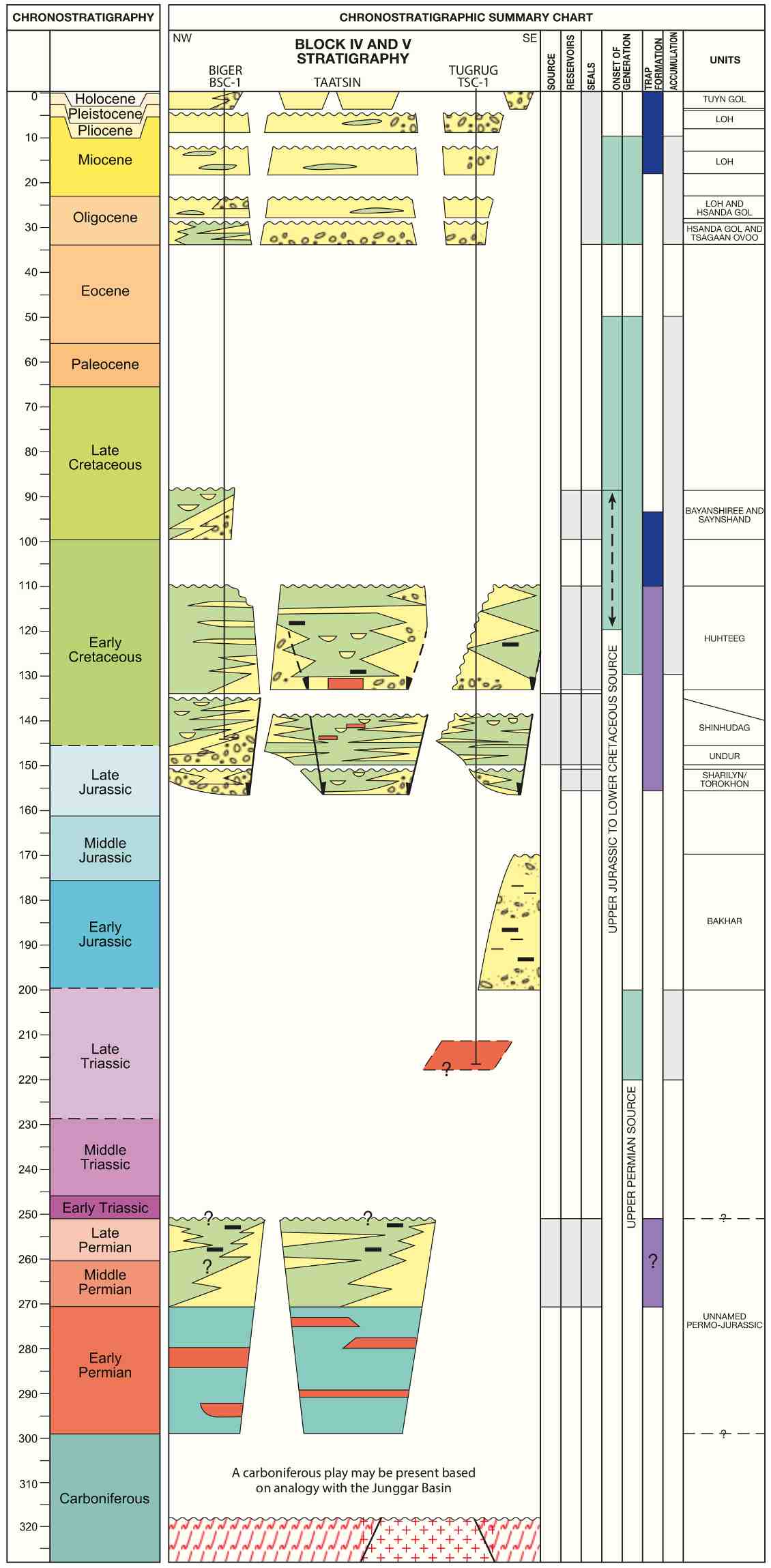

Stratigraphy of central Mongolia (Blocks IV and V), with a tectonic evolution and petroleum system overview. (Source: Modified after Fugro)Mongolia has a number of sedimentary basins, most of which are either undrilled or have been only sparsely explored. These basins, however, can be very large; at present over 290,000 km2 are under license, which is more than the land area of the UK! There are a further 240,000 km2 that are pending or study licenses. Currently 14 oil companies have interests in Mongolia but they are all small and most are inactive, holding large positions on a speculative or study basis. Only PetroChina is actively drilling and producing, with Petro Matad as the most active explorer in the frontier areas.

Stratigraphy of central Mongolia (Blocks IV and V), with a tectonic evolution and petroleum system overview. (Source: Modified after Fugro)Mongolia has a number of sedimentary basins, most of which are either undrilled or have been only sparsely explored. These basins, however, can be very large; at present over 290,000 km2 are under license, which is more than the land area of the UK! There are a further 240,000 km2 that are pending or study licenses. Currently 14 oil companies have interests in Mongolia but they are all small and most are inactive, holding large positions on a speculative or study basis. Only PetroChina is actively drilling and producing, with Petro Matad as the most active explorer in the frontier areas.

Petro Matad has recently completed extensive regional evaluations, focused on the central Block IV and V areas, as well as Block XX. The company has integrated four seasons of field work with modern 2D seismic and four stratigraphic core holes, and has highlighted a number of highly prospective areas which are worthy of further exploration. Total basin fill of 3,000–5,000m is common, despite large scale inversion since the Mesozoic and Tertiary.

The oldest megasequence is a PermoCarboniferous to Jurassic pre-rift section, which marked the transition from marine passive margin stratigraphy of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean to non-marine succession following northward drift of a number of micro-continents, with the closure of Paleo-Tethys and the formation of the Mongolian/Chinese lithosphere. Limestones overlain by fluvio-lacustrine coals and clastics are the dominant litho logies. This continent-continent collisional event resulted in regional up lift, and the development of a regional angular unconformity at the end of the Jurassic. The pre-rift section is a source of economic coals, as well as abundant oil and gas in producing analog basins such as the Junggar and Turpan Basins in China.

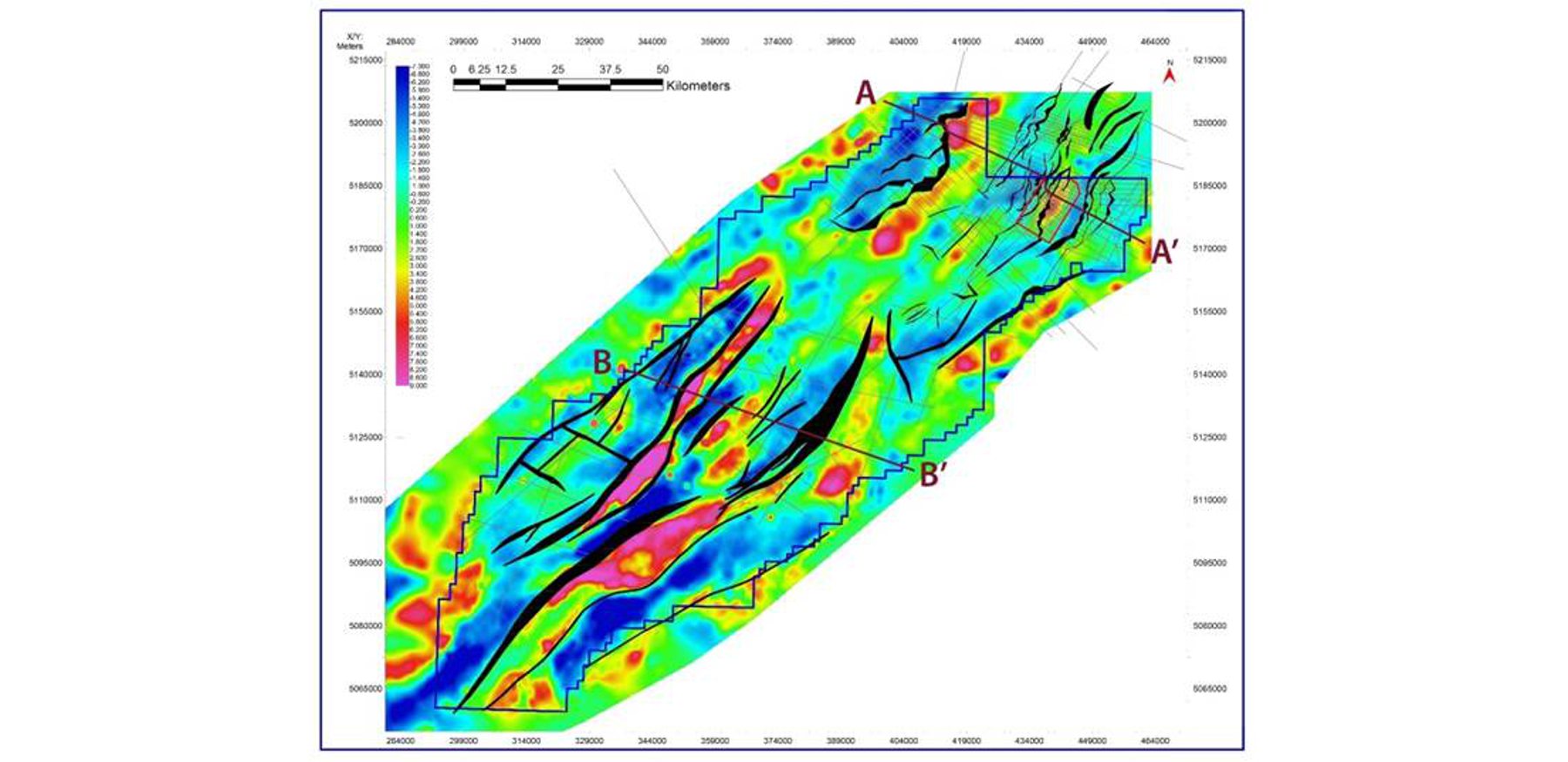

Section B-B’

Section B-B’Map showing subsurface structures, with cross sections A-A’ and B-B’, through Block XX, north-east Mongolia. The sections illustrate the large variety of potential trapping styles.

A large heat pulse then resulted in a major extensional phase, with a strike-slip component, continental collapse and development of a latest Jurassic Cretaceous syn-rift megasequence. This sequence comprises interbedded fluvio-lacustrine shales and sandstones, which are both source and reservoir for all of Mongolia’s currently proven hydrocarbons. This play is also dominant in several other Chinese basins, especially the Songliao and Erlian Basins to the east.

Extensional tectonics subsided by the mid-late Cretaceous, resulting in the development of a predominantly coarse clastic continental post-rift megasequence in all the topographic lows. Further inversion, however, was initiated in the Tertiary as a result of the northward collision of India to the south, and the emplacement of the Himalayan orogen. This resulted in a second major unconformity of Tertiary age and dominant compressional strike-slip tectonics. Most basins now have a clear strike-slip component with associated pull-aparts and compressional flower structures. Compression is still underway, with base level often >1000m above sea level.

As already mentioned, these basins are extremely analogous to many producing basins in China, with similar megasequences and lithology. The ingredients that result in multi-billion barrel reserves in China should therefore be present in the undrilled parts of Mongolia.

Potential for Large Discoveries

Clear evidence of the potential for a working petroleum system gathered by geoscientists from Petro Matad has highlighted the opportunity for large discoveries.

Across large areas of Block IV and V, fieldwork has proven the existence of syn-rift Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous lacustrine organic-rich shales interbedded with sandstones in the Shine Khudag Formation. TOC of samples in the Khoid Ulaan Bulag oil shale, with a net shale thickness of 265m, can range from 1.7% to 27% type I-II kerogen, and has a maximum HI of 800. The thickness and quality can vary, so that at Tsagaan Suvarga the average TOC is 5.3% (1.7–10.6%), but net thickness is 900m and HI reaches 900.

At almost every outcrop, many of which may have been deposited in a marginal lake setting, source rock quality is sufficient to result in significant generation if mature. Outcrop maturity averages around 0.6% VR, marginally mature for generation. Basin modeling, however, suggests that in much of the subsurface the source will be mature, with onset of generation in the early Cretaceous following syn-rift subsidence and burial.

Potential reservoir rocks of the syn-rift megasequence are also extensive in outcrop. Clean fluvio-deltaic sandstones of the Tsagaantsav or Shine Khudag Formations, with original porosities ranging from 10-30%, are extensive. These are often similar in age to the shales, and are sometimes even interbedded with them. Evidence of secondary quartz overgrowth or clay mineralization is rare, and porosity is preserved, even at depth in the stratigraphic boreholes.

Surface hydrocarbon seepages have not been observed to date, but core from the deepest stratigraphic borehole, TSC-1 in Block V, which was the only test to reach the syn-rift section, contained oil staining. Fluid inclusion studies also revealed significant hydrocarbon inclusions from a range of core and outcrop samples. These observations, plus the positive analogs from China and the producing basins in Mongolia, all point to the very high probability of a working syn-rift petroleum system. The pre-rift is in a much less advanced stage of evaluation, and is currently unproven in Mongolia. In China, however, this megasequence is a major oil and gas producer in such basins as the Tarim, Junggar and Turpan. Coals from this megasequence are already mined within Mongolia so hopefully further work will realize the potential of this deeper megasequence too.

Due to the complex history of extensional, compressional and strike slip tectonics, abundant trapping styles are identified on 2D seismic. These may consist of extensional features such as rotated fault blocks; compressional features, including thrusted anticlines, sub thrust plays and sub-unconformity plays; stratigraphic plays like pinch-outs or basin floor fans; or a combination of styles. This has resulted in the identification of abundant leads with multi-billion barrel resource potential.

The Time is Right

Syn-rift lacustrine sandstones, Argalant. (Source: Petro Matad)Mongolia is a very large country with a huge resource base that is just beginning to be exploited. With the mining sector dominating the investment market and resultant growth anticipated to be between 12–15% in the coming years, there is a large and growing demand for energy. So far this has not been realized through domestic production, but the time is right. Plans are underway for the country’s first refinery, and supplying domestic oil to fill the capacity makes both strategic and economic sense.

Syn-rift lacustrine sandstones, Argalant. (Source: Petro Matad)Mongolia is a very large country with a huge resource base that is just beginning to be exploited. With the mining sector dominating the investment market and resultant growth anticipated to be between 12–15% in the coming years, there is a large and growing demand for energy. So far this has not been realized through domestic production, but the time is right. Plans are underway for the country’s first refinery, and supplying domestic oil to fill the capacity makes both strategic and economic sense.

Mongolia is landlocked between Russia and China, which has created problems for foreign investors with concerns about delivery options in the past. But with the opening up of markets, especially in China, with oil already being exported there, these problems are disappearing. The country is becoming increasingly politically stable with a fast growing economy. New investment and petroleum laws have been recently implemented, and there are attractive fiscal terms, making economics robust. All this, plus very positive geological indicators, makes this frontier area one of the most attractive opportunities available for new investors in petroleum exploration.