A Global Focus

The energy geoscience industry operates offshore worldwide, engaging with governments, regulators, communities, other ocean users, and stakeholders. With this global reach comes the responsibility to operate alongside wildlife, especially in sensitive marine environments. To meet this responsibility, the industry implements mitigation measures intended to ensure negligible impacts. These measures rely on scientific evidence, and where science has limits, informed common sense. Effective mitigation must carefully consider and integrate biological, physical, and environmental factors. However, applying additional precaution to these mitigation measures often overestimates potential risk. In some instances, overly cautious approaches may even work contrary to broader environmental management goals.

Local implementation

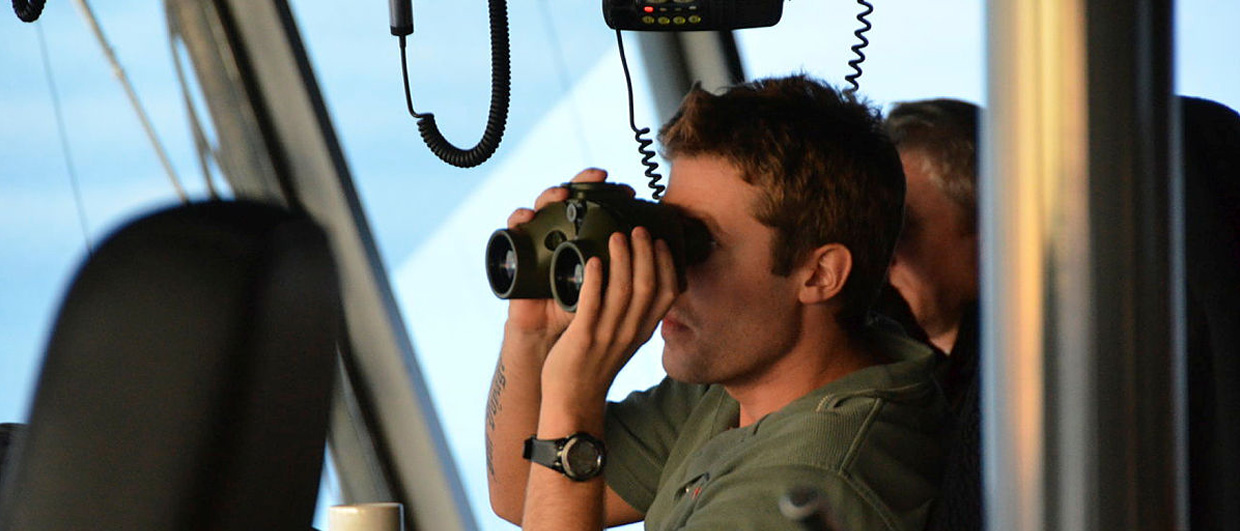

Mitigation measures are designed and implemented to protect marine mammals from potential hearing injury from close exposure to the acoustic source. Hearing capabilities and sensitivity to high-amplitude noise vary greatly among marine mammal groups. The extent to which impulsive sounds can cause either permanent threshold shifts (PTS) or temporary threshold shifts (TTS) — resulting in suppressed hearing capabilities over an affected frequency range — depends on the species’ hearing capabilities. Because “low-frequency cetaceans,” or baleen whales, have hearing that is most sensitive at lower frequencies, they generally the species of greatest focus during seismic survey operations (although there are notable exceptions among some higher-frequency hearing species that might be particularly reactive, such as porpoises).

Under typical operational parameters, any risk of PTS or TTS is generally confined to only tens to a few hundred meters from the source. Those potential risks are managed through mitigation measures that require the source to shut down when animals are detected within a specified radius. The exposure criteria set forth by Southall et al. (2019a, 2019b) have since been codified by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (2024) and are frequently used to set PTS and TTS thresholds in other regions.

Many jurisdictions and industry best practice recommendations use a standard 500-meter exclusion zone for marine mammals generally, both to ensure sufficient protection from injury and to simplify implementation for marine mammal observers. In some regions, regulators apply additional precaution by expanding this to 1000-meter or larger exclusion zones.

Is caution always the answer?

The precautionary principle in environmental management advocates conservative decision-making in cases when uncertainty exists (Jordan & O’Riordan, 2004). This approach generally reduces risk by erring on the side of environmental protection and avoiding potential irreversible consequences. Thoughtful application and interpretation of precaution is considered essential to responsible environmental risk management (Steel, 2013; Sunstein, 2003).

However, being overly cautious does not always generate additional benefits and can sometimes introduce unintended negative consequences. The original 500-meter exclusion zone is intended to provide sufficient protection against potential injury to marine mammals; expanding it to 1000 meters or more does not meaningfully enhance the level of protection provided to individual animals within the survey area. Shutting down survey operations to comply with a larger exclusion zone creates data gaps that must be filled later. Survey vessels are unable to stop or turn rapidly, so they must execute a line turn and transit back to complete imaging.

The additional time necessary to infill missing data extends the vessel’s presence on the water, generating additional atmospheric emissions and additional underwater sound in the environment. In trying to increase protection for individual animals, regulators may inadvertently impose greater exposure for marine mammal populations as a whole by increasing the overall chance of interactions with marine species, raising the background sound levels in the environment.

Integrated solutions

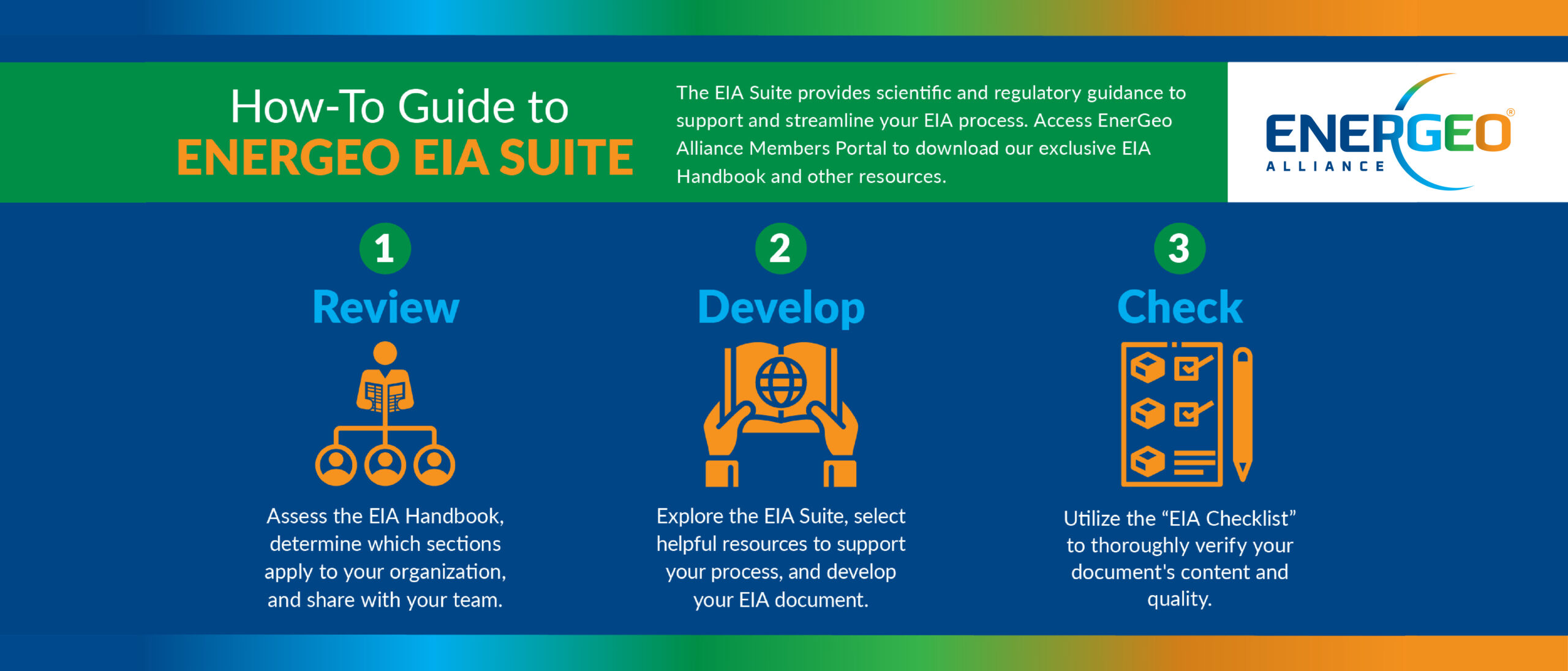

While precautionary measures may be necessary in certain circumstances, they must be balanced with practical implementation to avoid unintended consequences. Communicating both the benefits and limitations of these strategies is critical for evidence-based protocols. To support this, EnerGeo Alliance offers EA360, a platform providing comprehensive, tailored solutions for regulator engagement, public relations, and strategic consultation. These turnkey services integrate global expertise across science, policy, and communications, helping stakeholders align environmental protection with operational efficiency.

Comprehensive, proactively developed mitigation plans help regulators understand not just the “what” and “how” of the measures selected, but also the “why” that supports the strategy. Such plans should include operational controls, a fauna monitoring plan, the specific measures to be implemented, onboard communication protocols, and post-survey communication protocols. EnerGeo’s best practice Environmental Impact Assessment Handbook offers a thorough guide for developing these mitigation plans.

Summary

Regulators, industry, and stakeholders share a common goal when implementing mitigation measures: guaranteeing negligible impacts on wildlife while enabling the safe and sustainable collection of subsurface data. It is important to thoughtfully consider whether adding new layers of precaution to existing strategies is truly essential, and to ensure that doing so does not unintentionally create consequences in the quest to provide additional protection. EnerGeo Alliance’s member services support the industry in reducing environmental risk and communicating clearly with regulators and stakeholders alike.

References:

Jordan, A., & O’Riordan, T. (2004). The precautionary principle: A legal and policy history. In M. Martuzzi & J. A. Tickner (Eds.) The Precautionary Principle: Protecting Public Health, the Environment and the Future of Our Children (pp. 31-48). World Health Organization.

NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service). (2024). Update to: Technical Guidance for Assessing the Effects of Anthropogenic Sound on Marine Mammal Hearing (Version 3.0): Underwater and In-Air Criteria for Onset of Auditory Injury and Temporary Threshold Shifts. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-71.

Southall, B. L., Finneran, J. J., Reichmuth, C., Nachtigall, P. E., Ketten, D. R., Bowles, A. E., Ellison, W. T., Nowacek, D. P., & Tyack, P. L. (2019a). Marine mammal noise exposure criteria: Updated scientific recommendations for residual hearing effects. Aquatic Mammals, 45(2), 125-232.

Southall, B. L., Finneran, J. J., Reichmuth, C., Nachtigall, P. E., Ketten, D. R., Bowles, A. E., Ellison, W. T., Nowacek, D. P., & Tyack, P. L. (2019b). Errata: Marine mammal noise exposure criteria: Updated scientific recommendations for residual hearing effects. Aquatic Mammals, 45(5), 569-572.

Steel, D. (2013). The precautionary principle and the dilemma objection. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 16(3), 321-340.

Sunstein, C. R. (2003). Beyond the precautionary principle. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 151(3), 1003-1058.