Five years on, what has Mexico’s energy reform delivered for the country’s oil and gas exploration and production ambitions?

The Mexican Constitutional Energy Reform took place in 2014 in response to decreasing production, low oil prices, increasing foreign debt and competition from neighboring countries. It was the first time since 1938 that the country had opened its doors to foreign energy investment.

Over 100 Licenses Assigned

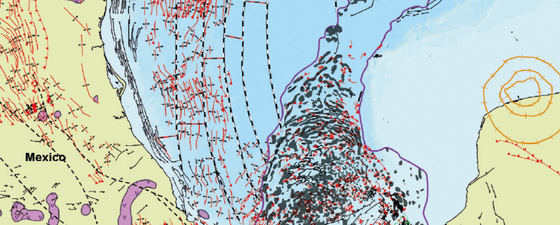

Figure 1: Over the past fi ve years 111 licenses have been assigned to foreign companies. Modifi ed from CNH 2019.

Though it got off to a disappointing start with only two out of the fourteen blocks successfully awarded in the first round (RD1.1), it wasn’t long before the license round bidding became competitive. Since then more than US$1.6 billion has been paid in signature bonuses. The consistency, transparency and persistence of the Mexican regulatory bodies over the past five years saw 111 licenses assigned and at least US$35 billion of investment from more than 76 companies (Figure 1), with commitments to drill a total of 413 wells for hydrocarbon exploration and extraction by 2023.

However, with the change in governmental regime in the latter part of 2018, the incoming administration has halted subsequent licensing rounds until the energy reform delivers on its committed work programs and production starts. This hiatus has advantages, in that it allows the service and support industries to prepare for the rapid growth and expansion of activities that is expected to occur in the next few years. More importantly, it will allow time for exploration wells to be drilled and evaluated in order to de-risk plays in the basin and allow companies and the government to sensibly allocate capital spending and drill fewer dry holes.

Figure 2: Investment in seismic acquisition and reprocessing activities (US$). Source: CNH 2019.

The country has benefitted from a requirement for companies to commit to a minimum percentage of capital investment on national content and various technology transfer initiatives, ranging from collaboration on projects with universities to the introduction of software and technology. The rapid pace of the license rounds saw more than US$3 billion invested in 2D and 3D seismic evaluations (Figure 2) and the energy reforms have already delivered considerable success with the billion-barrel Zama discovery, as well as the Cholula and Saasken discoveries (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Drilling results from exploration wells (March 2020).

Within just three years the Amoca-Mitzon-Tecoalli, Hokchi, Ichakil-Pokoch and Trion discoveries have been appraised by foreign oil companies, adding more than two billion barrels of 2P reserves (Figure 1). Mitzon first oil was in July 2019, producing 8,000 bopd, with Amoca and Tecoalli expected to come onstream in early 2021, producing a combined total of 100,000 bopd. Hokchi and Ichakil are projected to produce first oil by 2020. With PEMEX existing contracts, planned field developments and the extraction contracts assigned in the energy reform, peak production in 2021 is expected to be around 1.8 MMbopd, up from the current 1.6 MMbopd, although this is less than the 600,000 bopd expected by the government by 2025. Further increases will be dependent on exploration success from wells bid in license rounds following the energy reform.

What Were the Challenges?

There were definitely advantages for Premier Oil in being a first mover in terms of international companies, but entering any new international basin poses its own technical and operational challenges and the Sureste Basin was no different. There were a number of geological and geophysical questions, many common to entering any underexplored basin, especially in a country which is opening its doors to foreign energy investment for the first time in 76 years. Stringent regulatory compliance such as financial corporate guarantees and justification of technical capabilities as an operator were some of the barriers faced within a time-constrained environment of the license round. This was to ensure companies had the financial and technical capabilities to invest what they promised to deliver without having to be rescued by farm-outs or ending up with licenses sitting idle for years.

Sparse well data availability and inconsistencies in generic well data resulted in the need for significant investment of time spent on conditioning wireline logs and QC of reports. In many cases the seismic imaging was moderate quality at best, which challenged the imaging and mapping of salt-related traps. In the next few years, as discoveries are made and the race to first oil continues, there will be challenges in supply chain management and the construction of infrastructure whilst maintaining the national content requirement.

Exploration Risks Identified in Mexican Geological Basins

With nine main geological basins in Mexico, covering a diverse set of sedimentological and tectonic settings, comprising clastics, carbonates, extension, compression, strike-slip, salt diapirism, shale diapirism and even a meteorite impact there is nothing more a geologist could ask for! With natural oil seeps oozing at the seabed, one can easily be captivated by the untapped potential within this oil-mature province.

Figure 4: Gulf of Mexico structural elements – all the challenges a geologist could ask for!

Mexico shares its early geological history with the US Gulf of Mexico. Rifting initiated in the Middle Jurassic, providing the accommodation for deposition of the laterally extensive Louann and Campeche salt deposits and subsequent deposition of the world class Type II marine carbonate Tithonian source rock. The Chicxulub meteorite impact at the end of the Cretaceous is responsible for the carbonate fields to the east of Mexico. The Paleogene Laramide and Neogene Middle Miocene Chiapaneco compressional events resulted in rapid clastic deposition which influences the present day structural styles, such as salt-withdrawal mini-basins, salt diapirs and associated structures, compressional folds and listric faults.

In the early days of exploration, the focus was primarily on the Sureste Basin, also known as the Salina de Istmo, a proven prolific hydrocarbon province. It has produced in excess of 18 Bboe to date, mainly from Cretaceous carbonate reservoirs, and is known for the supergiant multi-billion barrel Cantarell oilfield, one of the largest anywhere in the world. Prospective resources are in the order of 13 Bbo and 6.5 Tcfg (CNH 2018). With current production focused mainly on the carbonates, the majority of the established clastic players entering the basin were drawn to the seismic ‘bright-spots’ in the supra-salt and salt flank plays with the poorly imaged sub-salt traps as a potential upside. Post-drill analysis of wells in the Miocene and Pliocene plays in the Sureste Basin revealed reservoir presence and seal as the main risks with a smaller percentage due to migration.

With wells few and far between and limited access to seismic angle stacks it was difficult to properly understand the amplitude responses especially in light of the fact that there are structural traps at similar depths and age without AVO responses. Having an understanding of the regional geology, including features such as tectonic history, petroleum systems expulsion and timing and gross depositional environment were important for prospect risking. To date, with ten other exploration wells drilled in the Sureste, we know that seismic ‘bright-spots’ are not always a reliable indicator of hydrocarbons, and wells which lack an AVO response were dry. The deepwater Sureste Basin (also known as the Campeche Basin), is a frontier experience testing unchartered territory, with the Norphlet and Wilcox plays (successful in the US Gulf of Mexico) targeted by wells in 2020, including Chibu-1, which is currently drilling (Figure 1). As further exploration wells are drilled in the basin, many of which target the clastic plays, the amplitude story will be unraveled and result in better drilling decisions.

What Does the Future Hold for Oil and Gas E&P in Mexico?

With more than 77 committed exploration wells to be drilled in the next five years there will definitely be no slowing down of activity in Mexico. There is also the added advantage of being protected by the Production Sharing Contracts in a lower oil price environment. Plays will be de-risked and our understanding of the petroleum systems of the Mexican sector of the Gulf of Mexico will evolve rapidly. Billion-barrel fields will be few and far between due to confined trapping geometries, and it is thought that many discoveries are likely to contain recoverable reserves in the 50-250 MMboe range, requiring cluster developments. This could potentially lead to another wave of divestments and acquisitions in the next 3-5 years.

The energy reform can help reverse Mexico’s declining production and contribute toward the government achieving its goal of increasing production by 600,000 bopd by 2025. However, this will require greater collaboration between the international oil companies and the Mexican regulatory bodies in order to reduce the timeline from discovery to first oil without compromising technical and HSES standards. Clarity from the Mexican government on the future for foreign investment in the Mexican energy sector will be advantageous. The future could be a period in country’s history of increasing production and development of the Mexican economy as a whole, placing its people and the country on a global stage with other producing countries worldwide.

Further Reading on Oil and Gas in Mexico

New Insights Revealed Into the Hydrocarbon Potential Along the Gulf of Mexico Conjugate Margins

Thomas Smith

Enhanced mega-regional hydrocarbon play and reservoir fairway maps in the Gulf of Mexico have resulted from improved tectonic restorations of its US and Mexican conjugate margins.

This article appeared in Vol. 15, No. 6 – 2018

Vast Potential: Mexico’s Offshore Ronda Uno

Ian Davison, Eoin O’Beirne, Theodore Faull and Ian Steel, Earthmoves Ltd.

An insight into some highlights of the offshore hydrocarbon potential available in almost virgin exploration territory.

This article appeared in Vol. 12, No. 2 – 2015