“The Golden Zone concept and its clear significance for understanding oil and gas occurrence seem not to be widely known within the petroleum industry”, write Paul Nadeau, Shaoqing Sun and Stephen Ehrenberg in a paper they published in Marine and Petroleum Geology a few days ago.

What is the Golden Zone? It is the subsurface temperature range within which most volumes of hydrocarbons have been found across the world, corresponding to an upper limit of 122°C and a lower limit of 60°C.

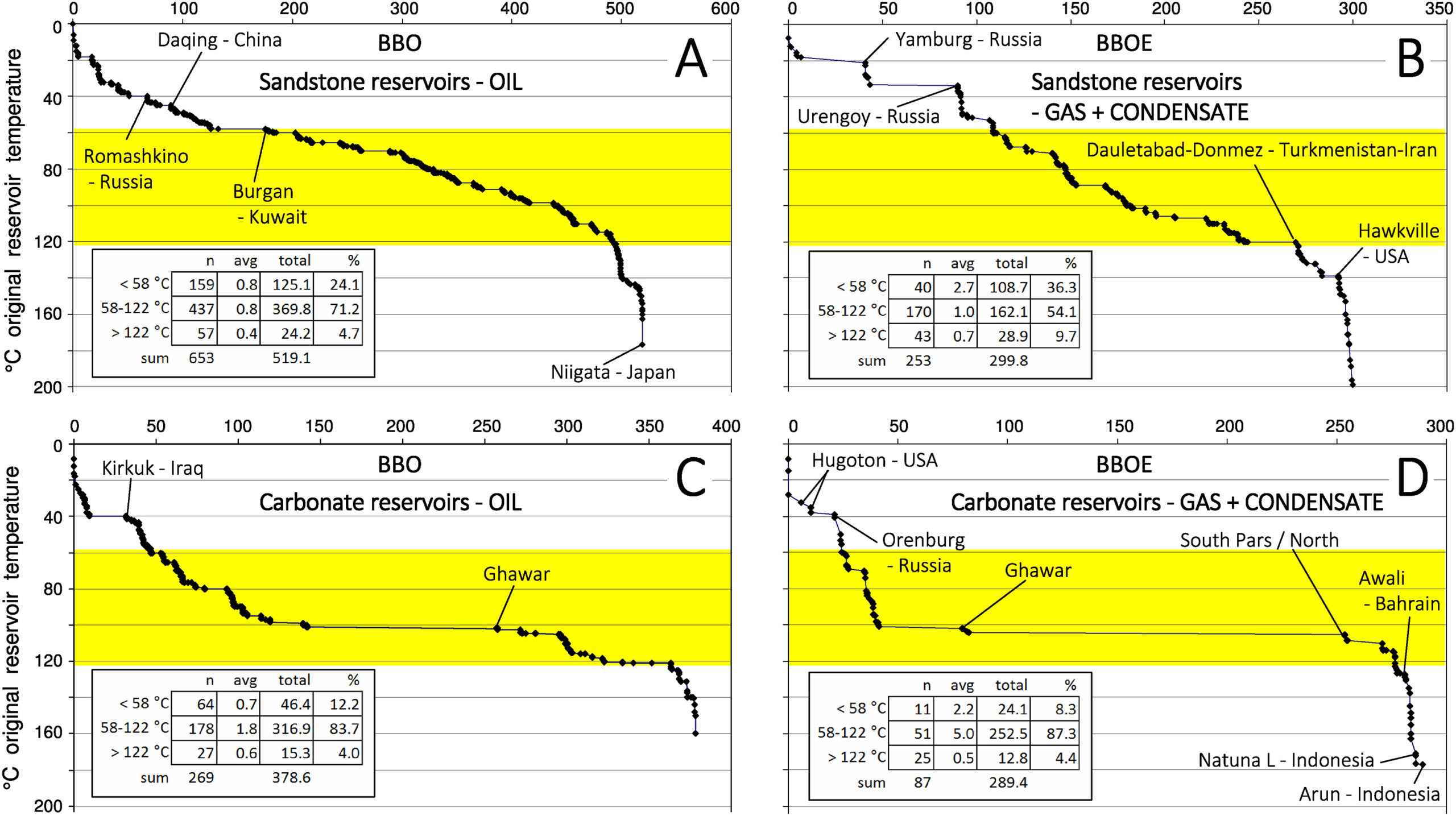

Using a global database of 954 fields, the researchers found that 74% of the volumes in the fields they looked at, representing around 50% of the world’s known reserves, occur within this temperature range. Particularly beyond the 122°C mark, the drop off in volumes is “precipitous” according to the authors, whilst a slower decrease is observed when moving to lower temperatures.

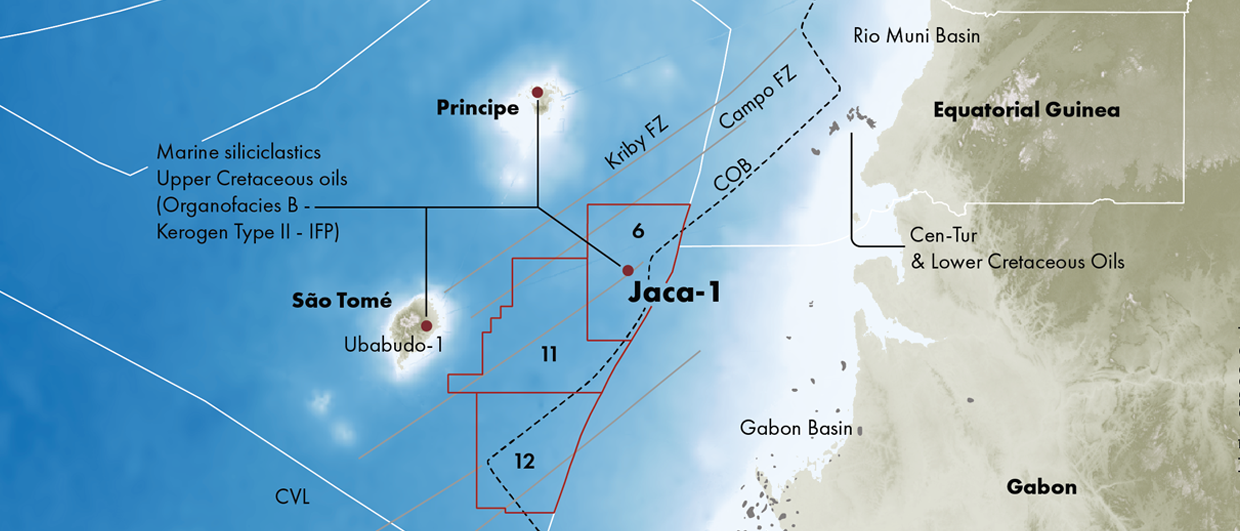

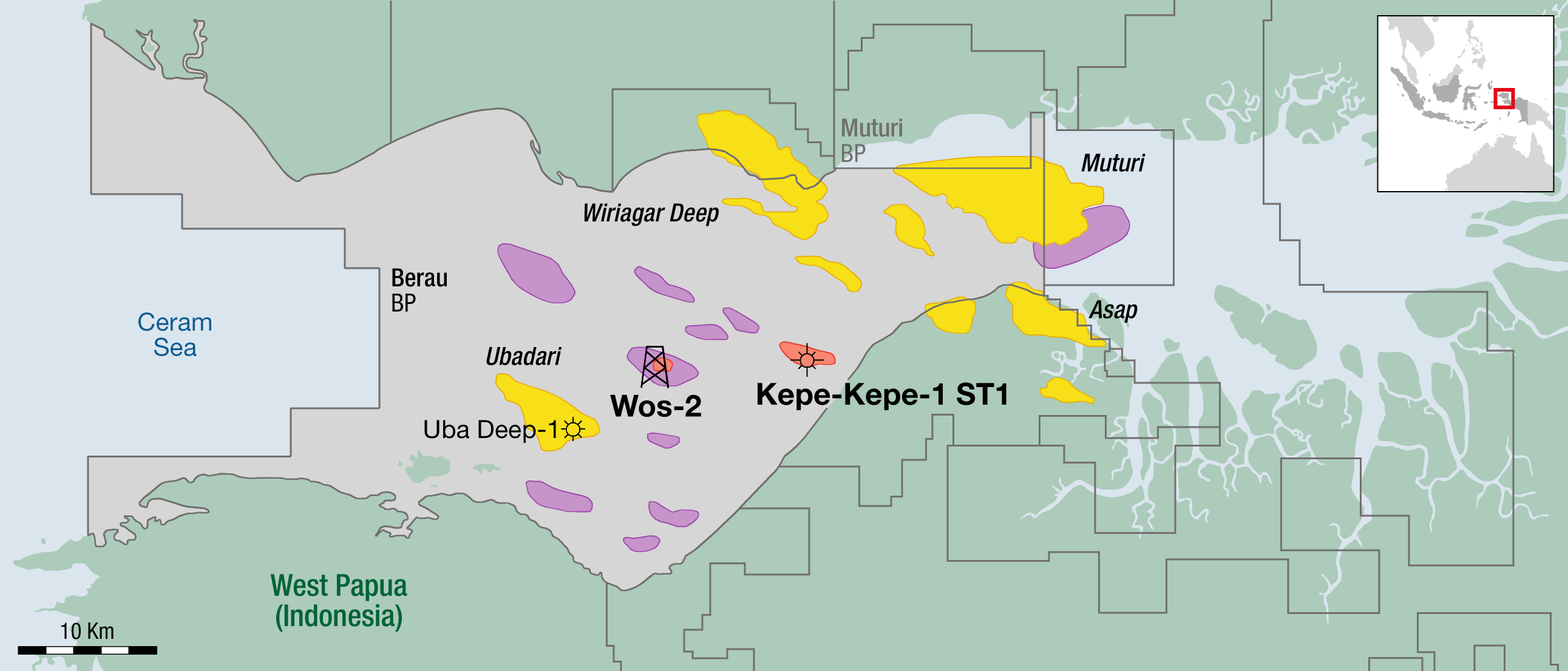

The interesting observation the researchers made, is that the Golden Zone is very much a global phenomenon, independent of reservoir and seal lithologies or petroleum type. There are regional variations and local exceptions, as is described in the paper, but reservoir temperature has shown to be a key factor in risking exploration campaigns.

The upper limit

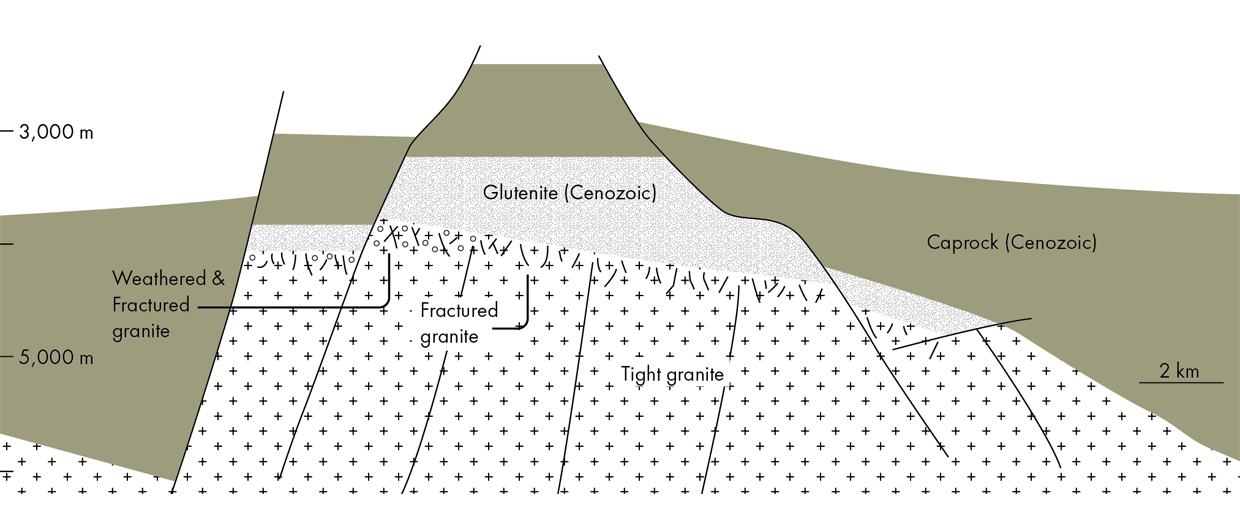

The sudden drop off in reserves beyond the 122°C mark is most likely caused by overpressure build-up and associated seal failure, combined with a reduction in trap size and decreasing reservoir quality due to cementation. It is maybe surprising to see that both siliciclastic and carbonate reservoirs display the same relationship between Estimated Ultimate Recoverable (EUR) and temperature, with the latter having only 4% of EUR in temperatures higher than 122°C. One explanation presented is that many carbonate strata are interbedded with siliciclastics that will increase fluid migration as quartz cementation kicks in in the siliciclatic zones and thereby also stimulating diagenesis in carbonate successions. Yet, as the authors note, most carbonate field in the Arabian province are near hydrostatic conditions and still have a sharp cut-off at 122°C, which requires more research.

The lower limit

Why is there not really the same cut-off at the lower end of the temperature range? Tectonic uplift and erosion are thought to be the main reasons, where hydrocarbon-bearing reservoirs that were buried more deeply before now find themselves at a shallower depth with the seal still intact. Another interesting observation the authors make is the higher proportion of gas in this lower temperature range (43% at <58°C as opposed to 35% at 58-122°C). Gas cap expansion and gas generation during biodegradation are two factors that are believed to explain this.

Should we go back to exploring the Golden Zone more?

In the discussion of the paper, the authors don’t shy away from arguing that a disproportionately high number of exploration wells drilled on the Norwegian Continental Shelf has targeted reservoirs in the >122°C zone where only about 7% of the EUR volumes reside. They also note that plenty of exploration opportunities are still waiting to be drilled within the Golden Zone, citing the 2010 Johan Sverdrup discovery as an example.

The question is if there are more Johan Sverdups hidden on the Norwegian Continental Shelf though. Saying that, the UKCS is currently seeing a well being drilled on the Devil’s Hole Horst, which was “mapped” and promoted by the late Niels Arveschoug as the “Johan Sverdrup of the UK sector”.