A recent conference in Dublin, entitled ‘Exploring Atlantic Ireland 2006: Investing in an Exciting Petroleum Province’, attracted more than 200 delegates from all over the world, with keynote speakers from both Irish and major international companies. “This is an encouraging sign that the industry is beginning to look at Ireland more favourably,” considers Noel Murphy, Petroleum Exploration Specialist at the Petroleum Affairs Division (PAD) of the Irish Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources.

Increasing Interest

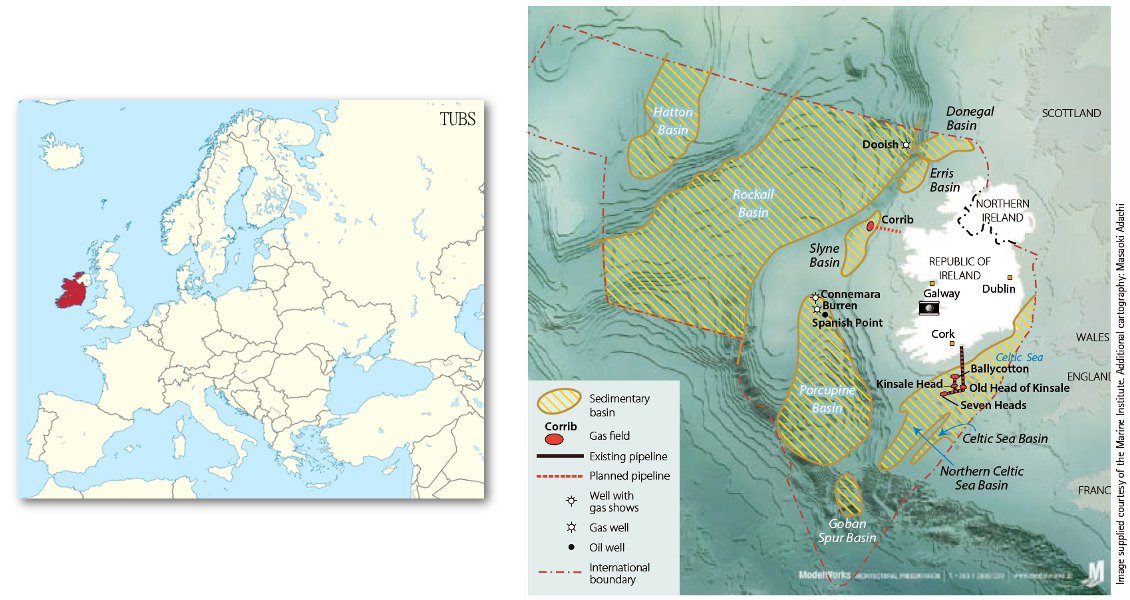

“Since 2003, we have seen an encouraging increase in interest in Ireland, which is particularly evident in licence uptake and farm-in activity,” Noel continues. “The 2006 Slyne-Erris-Donegal Basin Licensing Round attracted five applications, four of which were successful. Details on the new Porcupine Frontier Licensing Round, covering the deep water Porcupine Basin to the southwest of Ireland, have yet to be issued, but the area is already generating interest.”

The western coastline of Ireland is spectacularly beautiful, ranging from deep fjords and cliffs to wide bays and sandy beaches, all backed by the mountains ringing the country. (Source: Jane Whaley)Noel believes there are a number of explanations for this increased attention, including the fact that the Irish government has recently been putting a great deal of effort into encouraging oil companies to look seriously at Ireland’s potential, driven by the need to decrease the country’s over-dependence on imported hydrocarbons. “Obviously, the present high oil price means that companies can afford to look at perceived higher risk countries again,” he says. “We realised that to persuade them to seriously consider Ireland, we needed to provide them with as much information as possible.”

The western coastline of Ireland is spectacularly beautiful, ranging from deep fjords and cliffs to wide bays and sandy beaches, all backed by the mountains ringing the country. (Source: Jane Whaley)Noel believes there are a number of explanations for this increased attention, including the fact that the Irish government has recently been putting a great deal of effort into encouraging oil companies to look seriously at Ireland’s potential, driven by the need to decrease the country’s over-dependence on imported hydrocarbons. “Obviously, the present high oil price means that companies can afford to look at perceived higher risk countries again,” he says. “We realised that to persuade them to seriously consider Ireland, we needed to provide them with as much information as possible.”

The Department participates in key international seminars and conferences, providing the oil industry with a shop window on Ireland’s unexplored potential. “Joint industry- government groups have been funding strategic data acquisition and applied research,” Noel explains, “and the Department has sponsored regional assessments of yet-to-find petroleum potential. International research collaboration has also been important. For example, input from experts in eastern Canada and Europe have allowed us to build exciting new models predicting the development of world class reservoirs and source rocks in our Atlantic basins.”

Noel explains that “the Government’s aim is to promote increased industry participation in exploration offshore Ireland through a better understanding of the exploration potential and through making data more readily accessible. A regular licence round schedule is being introduced to facilitate industry planning and the acquisition of new data.”

Celtic Sea Gas

At present Ireland has no indigenous oil production, but produces gas from the northern Celtic Sea, off the south coast. The main reservoir is the Upper Cretaceous Greensand, a result of marine transgression caused by basin inversion in the southern Celtic Sea Basin. Lower Cretaceous shallow marine sands provide additional reservoirs. The gas is sourced from Lower Jurassic shales, matured for gas just before Tertiary inversion of the North Celtic Basin, which was probably responsible for most of the trap formation in this basin.

In 2006 Ireland’s total annual gas production was approximately 20 billion cubic feet (Bcf), or 566 million cubic metres (MMm3). The majority of this comes from the Kinsale Head field, about 50 km off the coast south of Cork. Total recoverable reserves are estimated at 1.65 Tcfg and, having started producing in 1978, the field peaked in 1995 at about 97 Bcf (2,750 MMm3) per annum. It has been in decline ever since, although small additional contributions of gas have been provided by the nearby Seven Heads and Ballycotton fields.

The young Irish company Island Oil and Gas has a number of interests in the Celtic Sea and in 2006 found Old Head of Kinsale, the first new gas discovery in the area for 16 years. This lies only 25 km from the Kinsale Head field and is estimated to have reserves of nearly 80 Bcf (2,250 MMm3) in both the Upper and Lower Cretaceous.

Deepwater Atlantic Province

The majority of the vast Irish offshore lies to the west of the country, in the hostile, deep water environment of the North Atlantic, with complex and poorly understood geology. The area is essentially unexplored – of the 123 exploration wells drilled in Irish waters to date, only 38 have been in these western waters. Fifteen of these recorded hydrocarbon shows.

The principal basins which form this ‘Atlantic Ireland’ province are Porcupine to the south-west, Slyne off the west coast, the Erris and Donegal Basins to the north-west and the distant ultra-deep water Rockall Basin, which stretches into the Atlantic to the west, as far as the Canadian border. According to Noel Murphy, the risked reserve potential for the Atlantic Ireland basins is comparable to that of neighbouring frontier regions. “We consider that the south-eastern Rockall and Porcupine Basins together may hold at least eight billion barrels of oil equivalent (Bboe), with a further billion barrels in the smaller Slyne, Erris and Donegal Basins together.”

The relatively unexplored Porcupine Basin is a north-south trending graben of Jurassic age, filled with Mesozoic and Tertiary sediments, which lie unconformably on Palaeozoic rocks. It is thought to have formed as a failed rift associated with the northward propagation of the Mid-Atlantic spreading ridge. Source rocks exist in the Jurassic and there are a number of potential reservoirs within the Middle Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous and Tertiary sections, providing non-marine, shelf and basinal plays.

Reappraisal Yields Results

Three fields were discovered in the northern part of the Porcupine Basin between 1979 and 1984. Connemara and Spanish Point found hydrocarbons in the Jurassic, while Burren has a Lower Cretaceous reservoir. All were initially thought uncommercial, but Island Oil and Gas is now confident that it can achieve a viable reserve base for Connemara and has recently announced successful farm-out activities there. Similarly, Spanish Point has been reappraised by new owners Providence Resources, and there are indications that the field may contain up to 1.4 Tcf (40 Bm3) of recoverable gas and 160 MMb (25 MMm3) oil.

The smaller Slyne, Erris and Donegal basins are also underexplored, with only nine exploration wells between them. Encouragingly, five of these have been drilled since 1996, leading to the discovery, of Corrib in the Slyne Basin. This field, found in 1996, has about 1.2 Tcf (34 Bm3) gas in place and proves the existence of a significant Triassic play. Environmental concerns with regards to the pipeline required to bring the gas to the onshore processing plant have slowed development, but the project is continuing and first gas is anticipated in 2009. Further exploration drilling is planned for the area next year.

Ultra-deep Water Plays

A simplified stratigraphic column for the deepwater Atlantic plays. (Source: Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources)Until very recently, the Rockall and southern Porcupine Basins saw little exploration. Water depths can reach 2,500 – 3,000m or more, and the source maturity and reservoirs are not well understood. In the Rockall Basin two discoveries, including Benbecula in the UK sector, prove that a working petroleum system exists. The 2002 Dooish discovery, about 125 km from the north-west coast, lies in 1,476 m of water, the second deepest water depth in which a well has been drilled in Irish waters. The well was not tested but encountered a 200m hydrocarbon column in good sandstone reservoirs of Carboniferous, Permian and Jurassic age.

A simplified stratigraphic column for the deepwater Atlantic plays. (Source: Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources)Until very recently, the Rockall and southern Porcupine Basins saw little exploration. Water depths can reach 2,500 – 3,000m or more, and the source maturity and reservoirs are not well understood. In the Rockall Basin two discoveries, including Benbecula in the UK sector, prove that a working petroleum system exists. The 2002 Dooish discovery, about 125 km from the north-west coast, lies in 1,476 m of water, the second deepest water depth in which a well has been drilled in Irish waters. The well was not tested but encountered a 200m hydrocarbon column in good sandstone reservoirs of Carboniferous, Permian and Jurassic age.

“Large sedimentary sub-basins are being revealed on both flanks of the Rockall Basin,” Noel explains. “We are finding what lies beneath the thick Tertiary cover and the discovery of Jurassic sediments in the Rockall is a big step forward.” Seismic shows that rifting followed by inversion has resulted in large tilted fault block structures in the Rockall and southern Porcupine Basins. Source rock modellingindicates that huge volumes of oil and gas may have been generated and expelled here. Meanwhile, palaeogoegraphic and provenance studies provide good support for the presence of regionally distributed reservoirs within various plays.

The Department believes that there are interesting prospects to be explored in the deep water basins. Improved geophysical techniques and data coverage will be the key to unlocking their hydrocarbon potential. “An encouraging sign of the renewed interest is the fact that four exploration wells are planned for Atlantic Ireland basins in 2008,” Noel says. “These are all substantial wells and one of them will be drilled on the same block as the Dooish discovery.”

Licensing Terms Review

Whilst applauding the Department for encouraging the petroleum industry, Fergus Cahill, Chairman of the Irish Offshore Operators Association (IOOA) sounds a cautionary note. “We expect an imminent announcement of a review of licensing terms. It is important to get these right. There has been pressure on the government to tighten tax levels, but we believe that the current fiscal terms are about right, given the historically low prospectivity offshore Ireland. We are particularly against the reintroduction of royalties on production, as suggested by some commentators, because this hits the profitability of marginal and high cost fields.”

“At the moment we have some of the most attractive production terms in the world, which is great, but you can’t have production without exploration,” Fergus continues. “Compare our situation with that in Norway, where an exploration well has about a 1 in 5 chance of success – and if it is dry, the government will reimburse 78% of the cost. Here in Ireland, the average success rate since the 1970’s has been 1 in 30 and all drilling costs – upwards of $70 million for a single deep water well – are borne by the oil company. We need to ensure that Ireland is an attractive proposition for exploration.”

Self-sufficient by 2020?

Ireland has a growing and young population and a thriving and energy hungry economy. (Source: Vincent Flynn)Ireland urgently needs new energy supplies for its growing population and thriving, energy-hungry economy. It now imports 85% of its gas requirements, in comparison to 1996, when about 95% of the country’s needs came from the Kinsale Head complex.

Ireland has a growing and young population and a thriving and energy hungry economy. (Source: Vincent Flynn)Ireland urgently needs new energy supplies for its growing population and thriving, energy-hungry economy. It now imports 85% of its gas requirements, in comparison to 1996, when about 95% of the country’s needs came from the Kinsale Head complex.

Ireland’s aim is to achieve selfsufficiency in hydrocarbon production by 2020, and it will be interesting to follow the success, or otherwise, of the Irish authorities in encouraging exploration.

Certainly the signs are heartening, with interest being shown in both newly offered acreage and in farm-in proposals. Exploration is on the increase, with four important deep water wells planned for 2008, as well as three wells in the Celtic Sea this year.

Ireland has a vast area of potentially hydrocarbon-bearing virgin offshore territory. As the Irish Marine Institute puts it, “Ireland is 90% undeveloped, undiscovered – and underwater.”