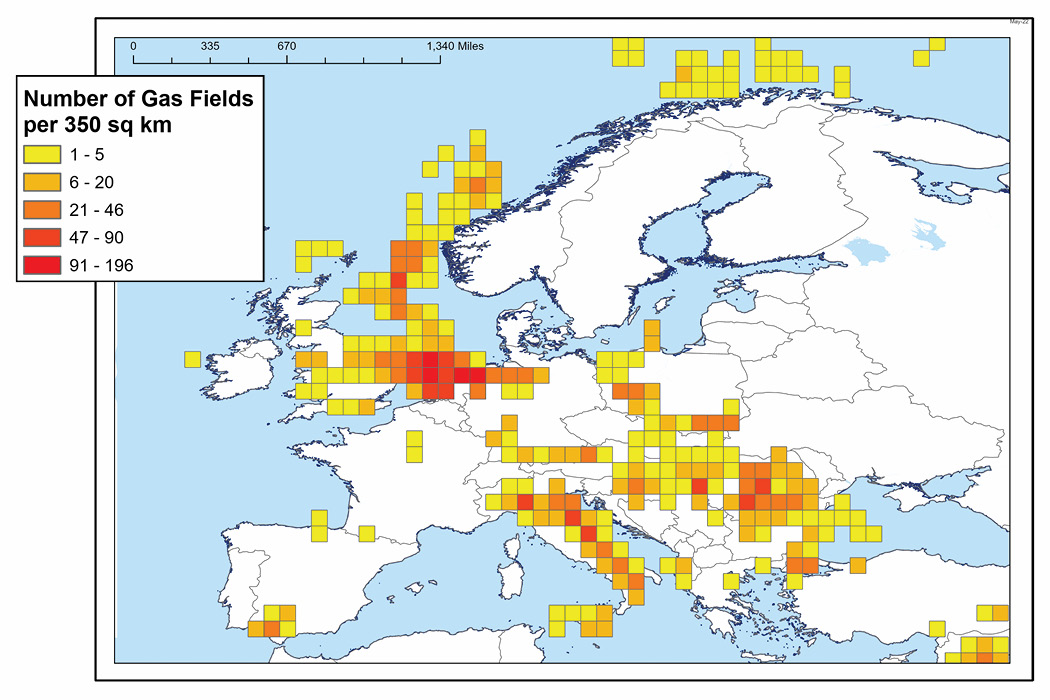

Energy demand continues to grow in Europe, where mature gas infrastructure across the region, built over many decades, has created a critical engagement with gas for domestic and industrial usage. Current events have recently led to a significant supply crunch for gas, driven by geo-political problems in Eastern Europe, declining production in mature basins, and environmental regulations and policy designed to discourage investment in new gas developments. As these macro-economic drivers have gathered pace over the last decade, the industry now witnesses new enthusiasm for conventional, home-grown gas production, and it is often the pioneering smaller exploration firms at the vanguard.

A summary tour of North-West Europe reveals that although anti-hydrocarbon legacies are threatening the major economies, there are signs of legislation and policy-making easing to allow a gas renaissance. Germany issued a statement recently explaining plans to re-evaluate their opportunities for gas in the German North Sea. Denmark made clear statements in 2020 regarding a future moratorium on oil and gas, and cancelled a bid round, but in 2022 the Ministry of Energy and Utilities countered this with a package of measures including ramping up gas production. TotalEnergies’ Tyra field will be the main beneficiary of this, and of course various green initiatives were announced at the same time. Britain’s INEOS will look to benefit at the Siri and Hejre area fields.

In Germany and Austria, the parastatal oil and gas companies of Wintershall and Ruhrgas may show restraint in running down gas production, while smaller firms such as ADX and Terrain are testing new plays in Bavaria and Austria.

The Netherlands is a fascinating example of the current push and pull of environmental policy versus strong socio-economic demand. The main gas producer there, the largest gas field in Europe at Groningen, is due to be shut in within the next four to five years. Production has already been reduced by 70% on the back of environmental concerns and some evidence of subsidence. Whilst the government there has recently said it will increase LNG (regas) capacity to manage the supply crunch in the short term, there are deafening calls to increase domestic gas production. Firms like ONE-DYAS and Kistos are happy to fill the gap in the meantime.

In the UK, where about 40% of gas supply is imported and another 20% from LNG, renewed efforts are being witnessed in the conventional heartland of the Southern North Sea and to some extent onshore England. The UK government announced updated policy guidelines recently, encouraging oil companies to refocus investment on domestic ‘energy’ production, of which gas is a major element and a relatively low hanging fruit. The business minister explicitly stated full support for the North Sea and challenged ‘naïve’ environmental activism that might restrict investment in domestic production. Increased investment in natural gas is bound to play a role in environmental initiatives to reduce reliance on coal and oil, and deliver energy and feedstock to blue hydrogen projects – relatively subtle concepts for some activists glued to carbon euphoria.

In the offshore UK, several agile explorers are bucking the trend as supermajors leave the old heartlands. Spirit Energy, Perenco and Harbour currently manage most of the traditional gas fields there, while firms like IOG and Hartshead are bringing new life back to overlooked fields and prospects. Hartshead are targeting development at Anning and Somerville in their first phase of exploration, pursuing resources of over 300 Bcf. IOG have commenced production from Elgood and Blythe, just two years from FDP approval, with 55 MMcfgd and 1 Mbcpd.

The firm is chasing several targets in Quad 48 including further drilling at Southwark and appraisal plans for Goddard and Kelham. Shell surprisingly withdrew recently from Egdon’s offshore gas basin licences in Quad 41 but remain committed to the Pensacola gas well penned in for 2023 with Deltic.

Traditional gas exploration onshore is not being ignored, with INEOS, UKOG and Egdon heeding the call for more gas. UKOG has small production in the Weald Basin in southern England, with significant potential at Horse Hill. INEOS accounts for 26 Mboepd in the major producing basins onshore UK, while IGas contribute around 2 Mboepd. Major potential for over 200 Bcf of untapped reserves has been revealed at West Newton, north of Hull. Junior explorers Rathlin, Reabold and Union Jack Oil have been working up this western edge of the European Permian basin for a number of years, and planning permission appears to be in place for imminent development. This could be the largest gas development onshore UK, one that will rely heavily on positive investment sentiment and clear policy direction from central and local government. Long-time onshore operator Egdon have reported a ‘step change’ in production and revenue, mainly from small gas-producing assets.

Whilst indications are strong for a renaissance in conventional gas in the UK and North-West Europe, shale gas may yet play a role, although public and technical barriers remain. In the UK for example the Business Secretary asked the British Geological Survey (BGS) to carry out a review on the impacts of fracking in 2022. Cuadrilla in the meantime has been asked not to fully abandon their shale gas wells in Lancashire. Large energy firms like INEOS, IGas and Centrica have substantial legacy shale gas licences, and all have started lobbying government to allow well testing and reconsider the current UK moratorium on shale gas fracking.

Author: Ian Blakeley, NVentures UK

www.nventures.co.uk