Companies exploring for natural hydrogen are rapidly popping up everywhere, but how do the geologists decide where to start prospecting? Many of them look at historical data from “dry” hydrocarbon wells to see whether they accidentally found hydrogen instead. However, subsurface H2 is formed by processes different from hydrocarbons, and hence, locations that were never on the radar for oil exploration might well be a good prospect for hydrogen.

So, rather than looking at legacy wells, exploring areas with known H2 surface seeps is also a good place to start. It has been found that H2 surface seeps regularly create easy-to-spot pock-marks at the surface, often called ‘fairy circles’. These semi-circular depressions are frequently filled with water and have vegetation growing around the edges. Fairy circles have been found all around the world, with examples in Russia, Mali, Brazil, the United States and Australia.

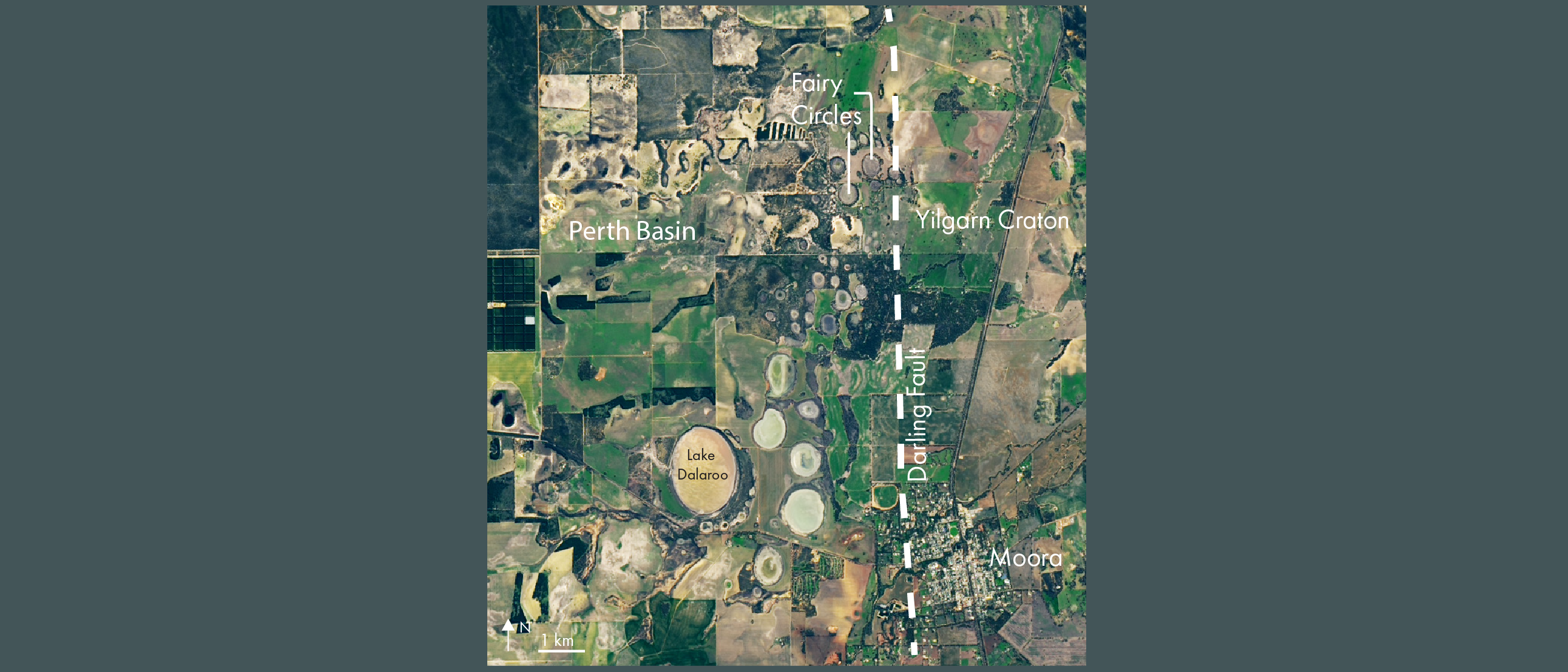

In the satellite image shown here, we see the many fairy circles near the town of Moora, located 150 km north of Perth in Western Australia. The fairy circles, locally known as salt lakes, vary in size from tens of meters to over a kilometre in diameter. They form a band along the eastern edge of the North Perth Basin, separated from the Yilgarn Carton by the Darling fault.

Hydrogen generation and challenges

The hydrogen is thought to be generated via serpentinization processes in deep aquifers that are in contact with Archean iron-rich basement. The gas subsequently migrates to the surface via the extensional fault network. Soil samples show that the fairy circles mainly seep H2 around their perimeters.

Yet, the discovery of H2 surface seeps does not automatically pave the way to announcing a commercial find. In contrast, the fact that seepage occurs can equally be an indication that the gas is not efficiently trapped in the subsurface. Therefore, additional work is required to firm this up.

The H2 seeps near Moora are all closely aligned with the Darling fault zone, which most likely acts as a conduit for the upward-migrating H2. Towards the centre of the Perth Basin, where fewer faults transect the overburden, it may be more likely that an H2 reservoir can be found if the play conditions of source, reservoir, and trap all prevail.