The offshore picture in East Africa is particularly promising, with the US Geological Survey estimating that coastal areas of Mozambique and Tanzania alone could harbour more than 250 Tcf of gas, in combination with 14.5 billion barrels of oil. Additionally, the success rate of companies looking for gas offshore is phenomenal: of the 27 wells drilled offshore Tanzania and Mozambique in the last two years, 24 have yielded discoveries. However, that elusive, commercial offshore oil discovery still remains to be found.

The oil and gas finds have also triggered a flurry of legislative changes, with outdated legislation and inadequate regulatory frameworks rapidly revised by governments anxious to attract, and to retain, investment by international players. The growth of the oil and gas industry in East Africa has been so rapid that it has strained not only the capacity but also the capabilities of governments, whose understandable caution often clashes with the aspirations of investors. Given this astonishing exploration success story, East Africa stands out as a global growth hot-spot.

Satellite map showing East Africa, where the USGS estimate that coastal areas of Mozambique and Tanzania could hold more than 250 Tcf of gas and 14.5 billion barrels of oil (Source: Fugro NPA).Oil discoveries onshore in Uganda and Kenya, coupled with world-class gas discoveries offshore in Tanzania and Mozambique, mean that every potential hydrocarbon basin across East Africa is the subject of intensive interest.

Satellite map showing East Africa, where the USGS estimate that coastal areas of Mozambique and Tanzania could hold more than 250 Tcf of gas and 14.5 billion barrels of oil (Source: Fugro NPA).Oil discoveries onshore in Uganda and Kenya, coupled with world-class gas discoveries offshore in Tanzania and Mozambique, mean that every potential hydrocarbon basin across East Africa is the subject of intensive interest.

Opportunity For Regional Development

Although the region is considered relatively stable politically, oil and gas companies face other challenges, including a lack of hydrocarbons production experience, poor infrastructure, an inadequate legal framework and bureaucratic inefficiency, along with corruption and security fears.

An emerging theme in the legislative changes in East Africa is the increasing level of local-content obligations that are being imposed. Rapid developments, however, have exhausted locally available skills and infrastructure, so operators must decide which of two, seemingly conflicting, licence obligations to observe; meet the local-content requirements, or ignore those requirements to ensure operations are conducted in accordance with best industry practice.

Chatham House, a source of independent analysis, notes that East Africa has an opportunity to use its new found oil and gas resources to enhance regional development and integration, and to avoid repeating the mistakes of emerging oil economies of the past. The region’s political leadership is being urged to show vision and foresight, in using these resources to enhance regional infrastructure, to reduce poverty and invest in education, and create diversified, globally competitive economies.

Choosing international partnerships carefully will be part of the challenge and much interest will focus on Kenya, a country whose economic and diplomatic clout suffered from a lack of known natural resources that are of strategic importance to the rest of the world. That is changing and the concern is that oil money might further blight an already corrupted political class.

Timing Key To Success

In summary, it is believed Uganda will become an oil producer over the medium term and looks set to become one of the five largest oil producers on the continent, with its Lake Albert oil fields potentially capable of producing 200-350,000 bo/d.

The finds in Tanzania and Mozambique are significant but there are concerns that neither country will be able to develop the potential before a glut of other new supplies pulls down prices. The US is expected to begin exports of LNG in 2015, with suggestions that annual volumes could reach around 70 Bcm by 2020 and, by 2016, Australia is expected to be exporting around 85 Bcm of LNG each year to Asia, closing in on top-ranked Qatar’s annual output of 100 Bcm.

These East African gas discoveries could support up to sixteen LNG trains but only two train developments have so far been proposed. Massive infrastructure investment will be required and billions of dollars of project finance will need to be raised on the international markets to fund it. Finally, Kenya is speedily developing some of its onshore and offshore potential but needs to show commercial viability for some of its finds, before it will really gain momentum.

COUNTRY BY COUNTRY REVIEW

Kenya

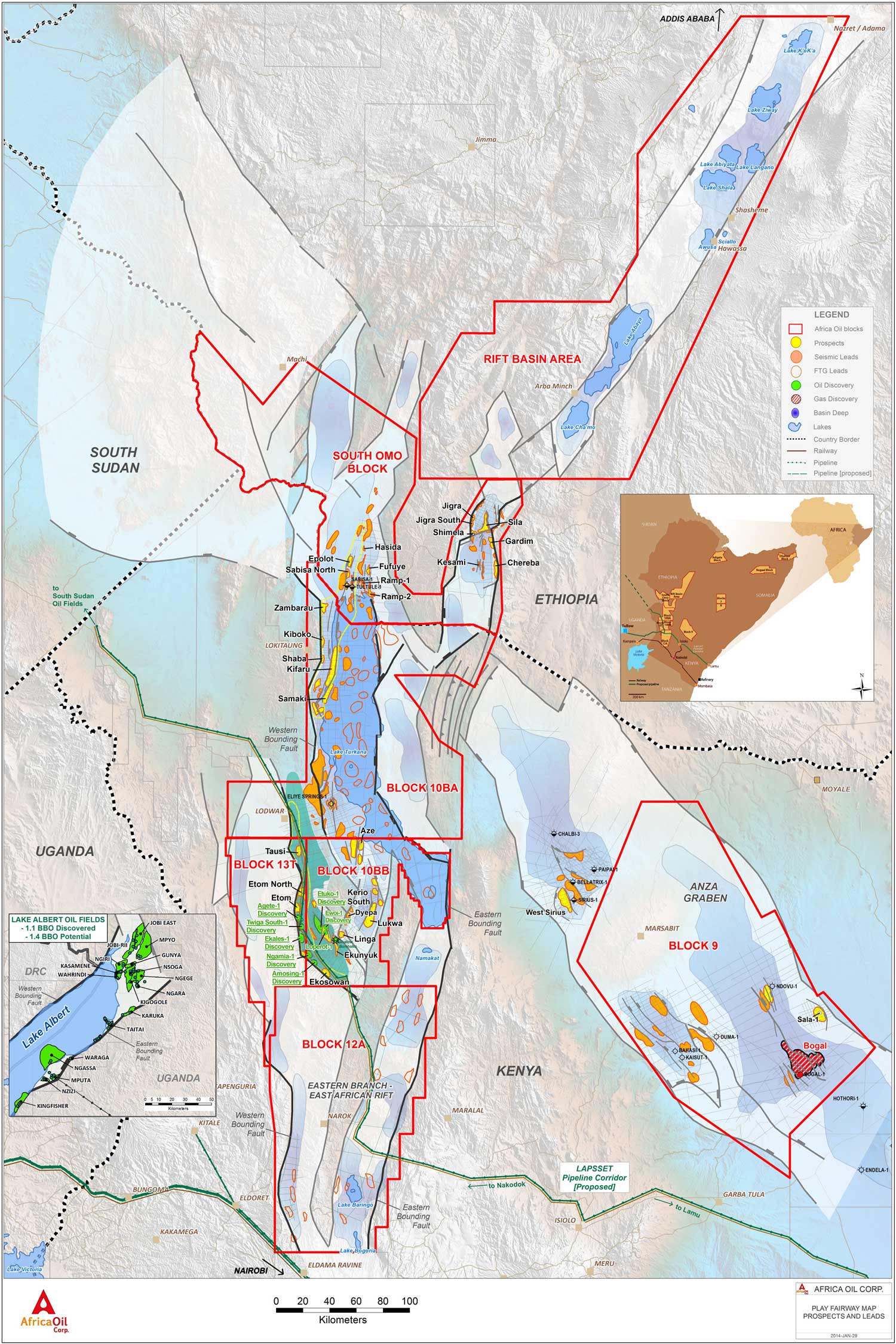

Industry interest in the exploration potential of Kenya was revived in 2012 when Tullow confirmed an oil discovery on its East Africa Rift Basin acreage. The first well in the basin, Ngamia-1, in Block 10BB, discovered over 200m of net oil pay and demonstrated that substantial oil generation has occurred in the South Lokichar Basin, one of 11 Tertiary rift basins in the company’s portfolio.

Further success quickly followed in this frontier basin and by January 2014, Tullow had confirmed PMean resources of over 600 MMbo, with the basin having a potential in excess of 1 billion barrels of oil. Tullow now expects to drill some 20 wells in Kenya and Ethiopia over the coming 18 months.

Operations have not been without issues. Works were suspended in October 2013, as a precautionary measure, due to demonstrations by locals over employment issues. Separately, the area has also seen clashes between local groups along the Kenya-Uganda border, with Tullow’s discovery of oil exacerbating existing tensions.

The discoveries also highlighted the inadequacies of the current petroleum legislation, last updated in 1986. A new Bill, detailing a clear legislative framework for oil and gas, covering upstream, midstream and downstream, is under construction and is expected to be approved by Parliament in June 2014. The new legislation is likely to include a number of profit-maximising measures including new taxes, a minimum state-stake in projects and local-content provision laws.

Map showing acreage position of Africa Oil Corp. with discoveries, prospects and leads (Source: Africa Oil Corp.)

Satellite map showing major basins and plays with discoveries and indicative resources. (Source: Africa Oil Corp.)Following the implementation of the new energy bill, the government has committed to review the terms for the natural gas sector, which are omitted from the current regulations. This is the reason energy ministry officials give to explain why companies have avoided drilling in areas with the potential for natural gas, as their contracts were solely focused on crude oil exploration.

Satellite map showing major basins and plays with discoveries and indicative resources. (Source: Africa Oil Corp.)Following the implementation of the new energy bill, the government has committed to review the terms for the natural gas sector, which are omitted from the current regulations. This is the reason energy ministry officials give to explain why companies have avoided drilling in areas with the potential for natural gas, as their contracts were solely focused on crude oil exploration.

Given Kenya’s location on the same geological belt as Tanzania and Mozambique, which have both seen significant recent gas discoveries, the government is hopeful for gas prospects. In 2012 Apache found gas in Mbawa-1 in offshore Block L8 but Kenya’s energy minister confirmed that while it was the country’s first offshore gas discovery, it was not large enough for commercial production.

In 2016, the Ministry of Energy will add seven additional blocks to increase the number of tracts in the country to 53. The government has already set up new bidding terms, including higher signature bonuses’ or an annual training fee. Unlicenced blocks are expected to be proposed for auction, once the new laws are in place.

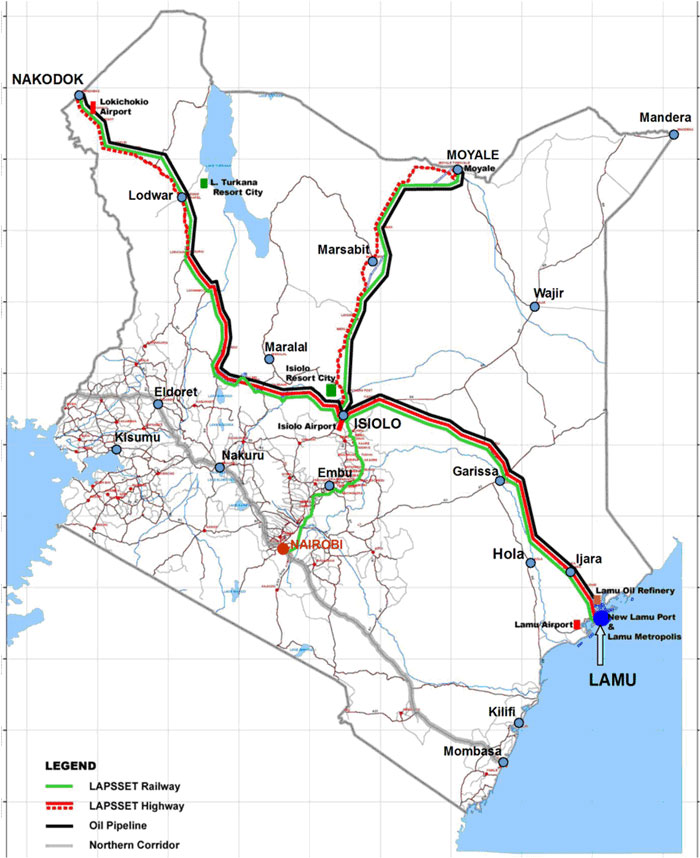

Map showing approximate route of planned LAPSSET pipeline and infrastructure. (Source: Kenya Vision 2030)Pipeline infrastructure is also advancing. In order to maximise the regional oil export capacity, an export pipeline cooperation agreement between Kenyan and Ugandan joint ventures has been concluded. This pipeline project seeks to deliver, for export, both Ugandan and Kenyan oil to Kenya’s newly built Indian Ocean port of Lamu.

Map showing approximate route of planned LAPSSET pipeline and infrastructure. (Source: Kenya Vision 2030)Pipeline infrastructure is also advancing. In order to maximise the regional oil export capacity, an export pipeline cooperation agreement between Kenyan and Ugandan joint ventures has been concluded. This pipeline project seeks to deliver, for export, both Ugandan and Kenyan oil to Kenya’s newly built Indian Ocean port of Lamu.

Kenya is also moving forward incrementally with its massive US$ 24 billion regional infrastructure project, the Lamu Port, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Transit Corridor (LAPSSET), the flagship project of Kenya’s Vision 2030 that aims to transform Kenya into a mid-level economy with 10% annual growth. Launched in March 2012, the project will link South Sudan and Ethiopia, both landlocked, to the Indian Ocean port and create the infrastructure necessary to bring East African hydrocarbons to international markets. Finding the funding for such a massive infrastructure project is proving challenging.

Mozambique

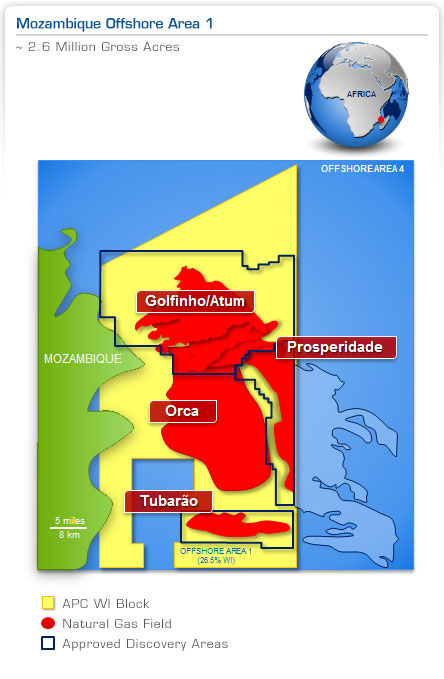

Map showing Mozambique offshore gas discoveries (Source: Anadarko Petroleum Corporation).Given the scope of exploration activities and plans to build LNG plants, Mozambique is widely considered to be one of the African countries that will be most able to boost its share of foreign investment. Most interest has focused on the northern, offshore, deepwater Rovuma Basin, following the discovery of a series of massive gas fields by both Anadarko and ENI.

Map showing Mozambique offshore gas discoveries (Source: Anadarko Petroleum Corporation).Given the scope of exploration activities and plans to build LNG plants, Mozambique is widely considered to be one of the African countries that will be most able to boost its share of foreign investment. Most interest has focused on the northern, offshore, deepwater Rovuma Basin, following the discovery of a series of massive gas fields by both Anadarko and ENI.

ENI’s recent 6 Tcf Mamba gas discovery has prompted management to comment that the company’s Area 4 may contain up to 90 Tcf gas in place. Meanwhile, Anadarko has made natural gas discoveries approaching 100 Tcf gas in place in its Offshore Area 1 block, a firm indicator of the country’s massive potential. Statoil and Petronas hold leases to the south, where speculation suggests the geology may favour oil.

Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos (ENH), Mozambique’s national oil company, has a stake in each of the exploration blocks, allowing for direct representation of the national interest at decision-making level. Consequently the government expects to carry its shareholding through to the development of each of the blocks and is pushing for a greater stake. While this push is driven by a desire to generate more profits from its natural resources, it is an undertaking that will represent a major challenge for the government, which believes that finance will not be a significant obstacle.

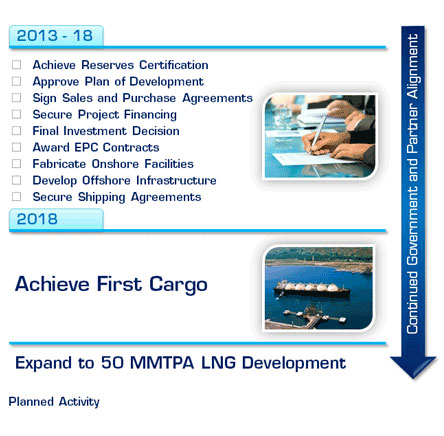

ENI and Anadarko are in the early stages of designing an onshore LNG facility in a remote area called Afungi, Cabo Delgado Province, in the northern part of Mozambique. The onshore two-train LNG plant, with an ultimate build cost of US$ 50 billion, is likely to be one of the largest in the world with at least 10 units, with a capacity of five million metric tons each. Plans also include an industrial zone around the LNG plants and a 2,100 km north south pipeline to help nurture local industries. But there are many obstacles and ENI has acknowledged that achieving first exports by 2018 will be “very challenging”.

Mozambique LNG Project Conceptual Timeline (Source: Anadarko Petroleum Corporation).ENI’s executive vice president for exploration, Luca Bertelli, “There’s no infrastructure, no logistics, so it will take a bit of time.” His statements come as the likely start-up date for the project has come under intense scrutiny, with ENH suggesting 2020 as the potential start date for the project. A floating operation for a fraction of the cost has been mooted, reflecting a major new push by the industry to find cheaper and more efficient ways to produce the natural gas that is locked under the sea in remote areas.

Mozambique LNG Project Conceptual Timeline (Source: Anadarko Petroleum Corporation).ENI’s executive vice president for exploration, Luca Bertelli, “There’s no infrastructure, no logistics, so it will take a bit of time.” His statements come as the likely start-up date for the project has come under intense scrutiny, with ENH suggesting 2020 as the potential start date for the project. A floating operation for a fraction of the cost has been mooted, reflecting a major new push by the industry to find cheaper and more efficient ways to produce the natural gas that is locked under the sea in remote areas.

According to Jose Branquinho, resource assessment director at the National Petroleum Institute (INP), Mozambique expects to launch its 5th licensing round in 2014. As many as 12 blocks in the deepwater Rovuma Basin, along with areas of the Zambezi Basin/Beira High and the Mozambique Basin, are to be offered. The acreage will be mostly offshore but could also include onshore areas.

The 5th licensing round has been delayed while the country updates its petroleum law, with a focus on legislation governing gas resources. The timeline may slip further, given that general elections are planned for October 2014 and the emergence of the opposition as a credible challenger.

The extended run of giant gas discoveries has overshadowed the fact that Mozambique will mark its first commercial production and sale of crude oil in 2014, with Sasol Petroleum bringing its onshore Inhassoro oil field onstream.

Tanzania

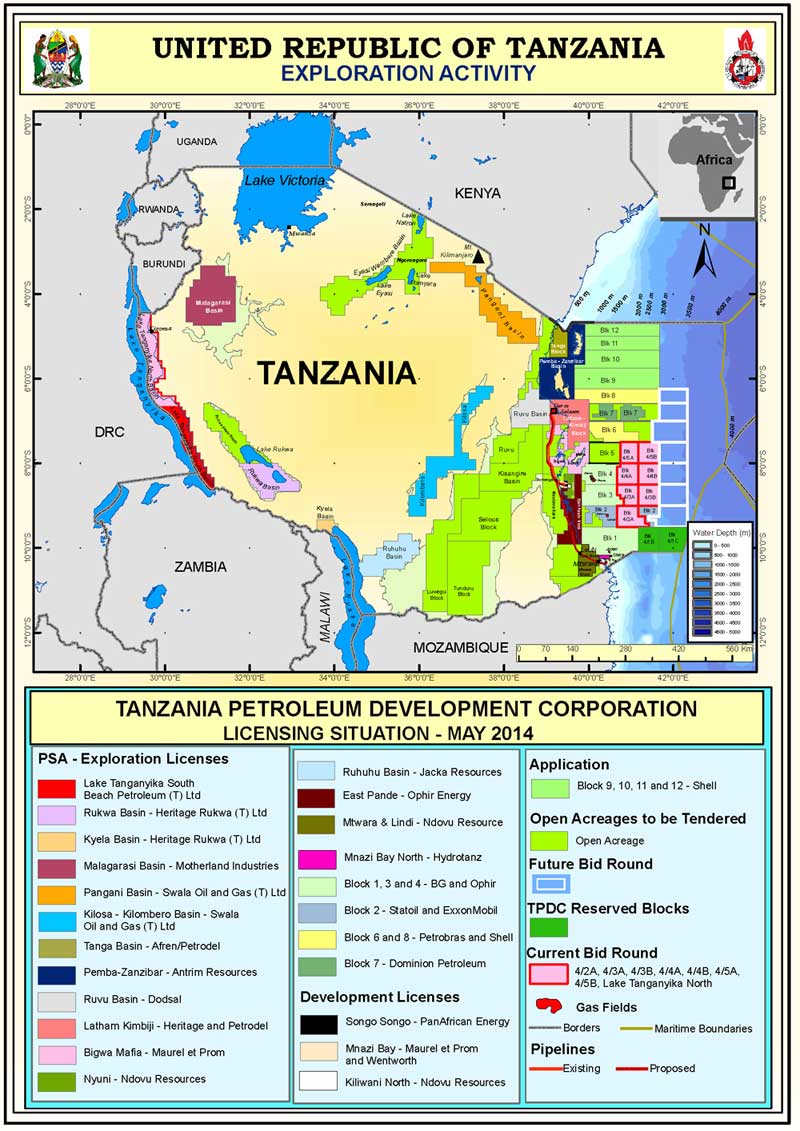

Exploration Activity and Licensing Situation, May 2014 (Source: Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation)Tanzania has no commercial oil discoveries but there are two small producing gas fields (Songo Songo and Mnazi Bay) that have taken decades to bring to commercial production, mainly because of the lack of a local market and limited export options due to reserves size. Recent gas discoveries in the deepwaters off Tanzania have raised recoverable gas reserves from 10 Tcf in 2012 to 42 Tcf, and have given a boost to the potential prospects for the hydrocarbon industry in the country. It is estimated that Tanzania’s upside gas potential is as much as 60 Tcf and continuing exploration is to be expected over the next decade.

Exploration Activity and Licensing Situation, May 2014 (Source: Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation)Tanzania has no commercial oil discoveries but there are two small producing gas fields (Songo Songo and Mnazi Bay) that have taken decades to bring to commercial production, mainly because of the lack of a local market and limited export options due to reserves size. Recent gas discoveries in the deepwaters off Tanzania have raised recoverable gas reserves from 10 Tcf in 2012 to 42 Tcf, and have given a boost to the potential prospects for the hydrocarbon industry in the country. It is estimated that Tanzania’s upside gas potential is as much as 60 Tcf and continuing exploration is to be expected over the next decade.

Exploration success has raised Tanzania’s profile as a potential supplier of LNG to Asian markets, along with neighbouring Mozambique. If an LNG export project were to advance, the IMF predicts that cumulative, foreign direct-investment into Tanzania could be in the US$ 20 – 30 billion range.

The government approved its natural gas policy late in 2013, a document that ensures the domestic market gets priority over exports, and is now drafting new laws to regulate the industry. The new model is financially more demanding for operators and seeks to maximise returns and benefits from E&P activities for the local population. However, debate rumbles on over how much gas should be sold to foreign investors and what safeguards should be put in place to ensure development of the country’s own gas and electricity sector. Adding to the mix, the government’s term ends in 2015, stirring political debate within the ruling party as well as among the opposition over the best approach.

Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) closed the 4th Tanzania Offshore and North Lake Tanganyika Licensing Round on 15 May 2014. Eight blocks were proposed for bidding, comprising seven deepwater blocks running south to north and the North Lake Tanganyika block located in the west branch of the East Africa Rift System. Five bids were received for four blocks but one bid was declared invalid; final results are yet to be published. Seven further blocks have been delineated for a future bid round.

TPDC intends to take a 25 – 35% state partnership in any permits and it is understood that TPDC will favour applications where international companies bid in joint venture or consortia with local companies, in-line with the new Model Production Sharing Agreement 2013.

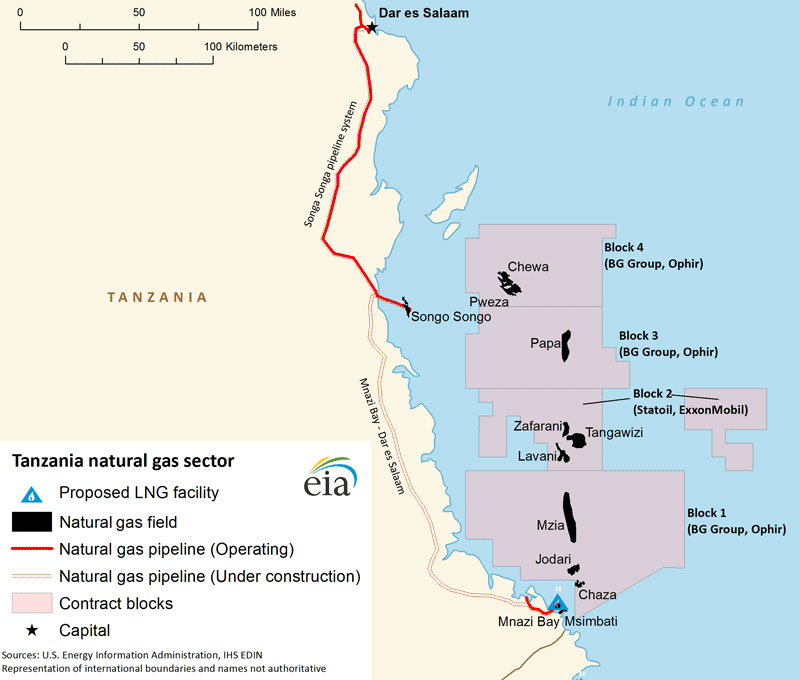

Tanzania Natural Gas Sector (Source: EIA).Operating deepwater Block 2, Statoil is evaluating development plans to exploit its three gas fields (Zafarani, Lavani and Tangawizi), for which it estimates in place reserves of 17–20 Tcf and recoverable reserves of 12–15 Tcf. The company plans to drill up to 12 exploration and appraisal wells in Tanzania by early 2015. However, Statoil and BG, which has also found multi Tcf gas reserves on adjoining Block 1, have found it difficult to monetise the discoveries, citing the inadequacies of the regulatory framework.

Tanzania Natural Gas Sector (Source: EIA).Operating deepwater Block 2, Statoil is evaluating development plans to exploit its three gas fields (Zafarani, Lavani and Tangawizi), for which it estimates in place reserves of 17–20 Tcf and recoverable reserves of 12–15 Tcf. The company plans to drill up to 12 exploration and appraisal wells in Tanzania by early 2015. However, Statoil and BG, which has also found multi Tcf gas reserves on adjoining Block 1, have found it difficult to monetise the discoveries, citing the inadequacies of the regulatory framework.

Statoil Chief Executive, Helge Lund, has called for “stable framework conditions”, that will enable the company to make a final investment decision (due by late 2016) on its proposed LNG project. The issues on which Statoil needs clarity are fundamental project issues such as the pricing of domestic gas, TPDC’s participation rights and confirmation of the overall Tanzanian government take from the project.

The first train of an initial two-train onshore LNG plant, to be located at Lindi, is scheduled to come onstream by end 2021. The option of a floating LNG project was rejected by the Energy & Minerals Minister, Sospeter Muhongo, in October 2013.

China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) is constructing the 540 km main East Tanzania Pipeline that includes a 25 km offshore section linking Mnazi Bay to shore. The line, with a capacity of 784 MMcfg/d, will run from Mnazi Bay in the Mtwara region to Songo Songo in the Kilwa District, and terminate at Dar es Salaam. This Chinese-funded project has witnessed bloody violence as locals protested government’s decision to pipe the gas to Dar es Salaam for refining and eventual sale, instead of building a refining plant in Mtwara. The incident exposed an inability to handle issues around the sharing of resources and how unprepared the region is in managing expectations and proceeds, as oil and gas exploration activities intensify. Also, an issue is a long-standing border dispute with Malawi, where potential exploration of Lake Malawi has fuelled tension. Malawi claims the whole lake as its territory while Tanzania claims half of it.

Uganda

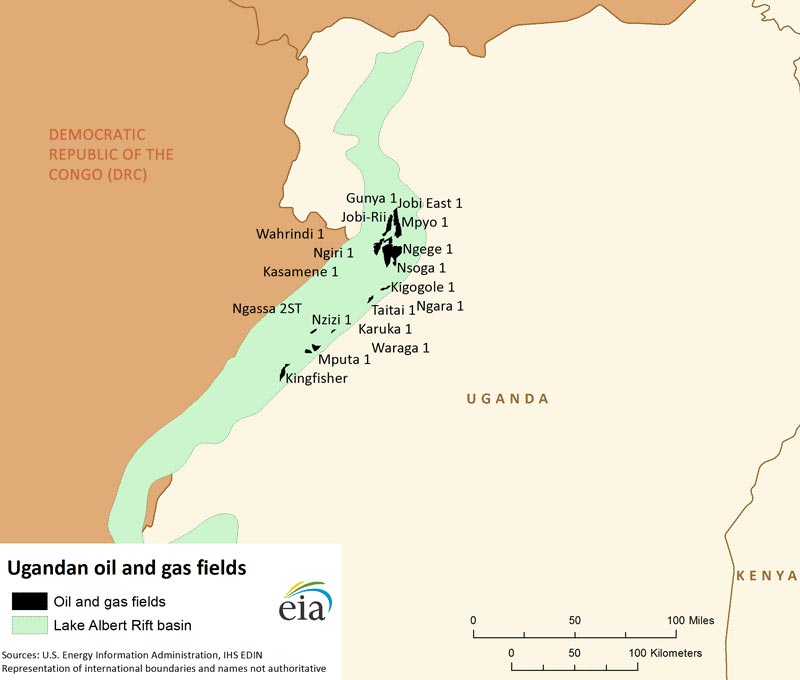

Uganda Oil and Gas Fields (Source: EIA).Tullow discovered commercially viable oil deposits in a remote and environmentally sensitive area of the Albertine Graben region in 2006. Unlike neighbouring countries that have moved quickly to commercialise hydrocarbons, the Ugandan authorities have frustrated Tullow and partners, CNOOC and Total, by being slow in getting these resources onstream and establishing effective management procedures to promote growth and development for the country. This situation is born out of Uganda’s national oil and gas policy that stipulates the development of a petrochemical industry based around an oil refinery and because of disagreement with the government on the capacity of the refinery. In addition, President Yoweri Museveni insisted many times that without a refinery, no drop of oil would be exported by the oil companies.

Uganda Oil and Gas Fields (Source: EIA).Tullow discovered commercially viable oil deposits in a remote and environmentally sensitive area of the Albertine Graben region in 2006. Unlike neighbouring countries that have moved quickly to commercialise hydrocarbons, the Ugandan authorities have frustrated Tullow and partners, CNOOC and Total, by being slow in getting these resources onstream and establishing effective management procedures to promote growth and development for the country. This situation is born out of Uganda’s national oil and gas policy that stipulates the development of a petrochemical industry based around an oil refinery and because of disagreement with the government on the capacity of the refinery. In addition, President Yoweri Museveni insisted many times that without a refinery, no drop of oil would be exported by the oil companies.

By the end of 2013, Uganda’s proven oil reserves were estimated by the Petroleum Exploration and Production Department to be 3.5 billion barrels. It is now believed that Uganda could be sitting on one of the biggest onshore oil reserves in sub Saharan Africa, suggesting foreign interest in the sector will likely remain strong for a good many years.

The breakthrough came in February 2014 with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding that unlocked a potential US$ 14 billion spend on vital infrastructure by the three oil companies to commence commercial oil productions. Plateau production from the four licences held by the consortium is expected to average 200,000 to 230,000 b/d.

In addition to field developments and refinery construction, the agreement includes the construction of an export pipeline to Lamu in Kenya. Kenya is to co-ordinate the development of the pipeline, which would also transport its own recent discoveries, and South Sudan has retained the possibility of involvement in the project as an alternative export route.

Bowing to pressure from the Ugandan government, the partners have compromised on providing feedstock to a 30–60,000 b/d phased oil refinery, expected to come online in 2018, to supply local and regional markets. The deal indicates a new momentum within Uganda’s government to facilitate some development of oil; a final investment decision is targeted for 2015. The Ugandan authorities anticipate crude exports to begin as early as 2018.

The signing may have come too late for Tullow, which has seen its Kenya assets (discovered in 2012, five years after the Uganda discoveries) progress rapidly thanks to a more supportive government. According to Tullow chief operating officer Paul McDade, “as we look at the phasing of our investments there’s a lot of priority being given to Kenya. If it continues to be very material and grow then we may look to modify our holdings in Uganda.”

President Yoweri Museveni finally signed the Petroleum (Exploration, Development and Production) Act and it was gazetted on 5 April 2013. However, it is believed he is yet to sign the Petroleum (Refining, Gas Processing and Conversion, Transportation and Storage) Bill, 2012, which has been approved by Parliament, and the Public Finance Bill, which has the petroleum revenue management element embedded in it which is still before Parliament.

There has been a moratorium on granting exploration licences since 2011, but subject to the necessary legislation the government plans to offer 13 blocks in a licensing round; current open acreage covers approximately 17,400 km2.