Many people on LinkedIn wrote about the dramatic decline in oil production from Venezuela from 3 million barrels a day in 1998 to only a third of that twenty years later. How could this happen? Based on conversations with two people who worked for Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA) at the time Hugo Chávez took power in 1999, there is at least one factor uncovered that explains why this happened: the mass sacking of most of the technical staff. In one go.

Before going into this, it is important to stress that the names of the people quoted here are fictitious. That is to guarantee the safety not so much for themselves, as they are abroad already, but for any remaining family members staying in Venezuela. Because the people who are there have not had a chance to celebrate the potential new chapter the country is entering now.

In contrast, there is a lockdown in place in Venezuela right now and people who are found walking the streets without a good reason can be asked to show their mobile phones by the colectivos, a gang funded by the Maduro regime. If there is any negative commentary about the government in their chats, they are in serious trouble.

So, even though there are no celebrations in Venezuela at the moment, for many there is a glimmer of hope that things will change. For the two people I spoke to, Susan and Jennifer, 26 years of oil industry destruction may have come to an end. The contrast with how the company looked when this all started in 1999, when they were both working for PDVSA, is stark.

“Let’s start by saying that our country was not perfect in the late nineties,” says Susan. “There was corruption, there was inequality and there were certainly aspects of society that needed to be improved. But at the same time, we had opportunities to build a career, also for people from humble backgrounds.”

If you grow up in an oil country, it is your dream to work in the oil and gas industry

What is really striking is that both Susan and Jennifer specifically mentioned the pride that came with working for PDVSA. It was a goal in life to get there, also because the recruitment process was very much based on merit and not on background.

“When I was in year 7, I knew that I wanted to be a geologist and work in the oil and gas industry,” says Jennifer, “even though I lived in the mountains where there was no oil production whatsoever.”

“In Britain, people speak about Henry the VIII,” she continued, “but in Venezuela, people talk about the times when the oil industry kicked off. It is a matter of pride. People know about the first well that started production in 1914 – Zumaque-1 on the eastern border of Lake Maracaibo. We grew up with that.”

Whilst she was still studying, Jennifer was offered a scholarship by PVDSA. “It was the sign that you were going to be offered a job after that,” she says. The scholarship also came with six-week-long internships in the company; visiting the rigs, doing well correlation exercises, and looking at cores. “It was a taster,” she says, “almost like this is how it’s going to be when you join us, even before I had formally signed a contract.”

“But from the moment I did indeed join the company, I had the same experience as during my scholarship; having the chance to look at different divisions of the company and getting familiar with a diverse range of business lines, from upstream to midstream. In addition, you still had to study and get good grades.”

After this first year, Jennifer was sent to a smaller subsidiary office along the shores of Lake Maracaibo. “I had to work hard, and the place wasn’t very attractive, but hey, there was a lot of oil around. We also received a bonus twice a year, a Christmas and a production bonus. Really, my only incentive to leave my job was to do a master’s degree or PhD abroad, and then come back to the country.”

Susan’s experience is similar. “At the end of my studies,” she says, “I was fortunate to get a 6-month internship with INTEVEP, the Research and Development Centre of PDVSA. It was a huge facility, almost a city, with world-class labs, just outside Caracas. It was a great working environment with lots of high-skilled and technical people. It became even better when I was offered a job before the end of my internship as well, in 1997. The atmosphere was very much like in the West,” she continues. “Nobody cared about which politician you favoured; it was very much based on how you performed technically. As it should be.”

But the working environment started to change quickly when Chávez took power in 1999.

“As expected,” Susan said, “once Chávez started his presidency, the first thing he targeted was PDVSA. Before his time, it was a relatively independent company, even though it was owned by the state. The money that was made was paid to the government in the form of royalties and taxes, but a significant part of the profit was reinvested to improve equipment, technology and human resources.”

The Chávez administration changed the game, and started to use PDVSA as the cash cow to fund his Socialist Revolution, with no control whatsoever, leaving PDVSA without the means to reinvest and improve the main source of income for the country. “I personally saw politicians visiting our labs in PDVSA, not for ceremonial purposes, but to start gathering information of who was supporting the revolution and who was not,” says Susan.

Chávez also started to replace managers at all levels with people from the military who had no clue about the industry.

For Susan herself, it was obvious that the new doctrine was a recipe for failure. “We had a couple of colleagues from Cuba in our team,” she says, “both with PhD’s from Russia. They fled the country in the mid-1990s, as there was a lack of everything, including essentials such as food and electricity. They had to create their own soap in the labs, using pig fats. When he came to Venezuela, he ate so much beef that it made him ill for a month. And we all knew that Cuba formed a shining example for Chávez.”

As the situation in the country deteriorated, mass strikes started to take place in 2002. There was also pressure from outside for PDVSA workers to join the strike. “We were seen as privileged,” says Susan, “and to an extent, that was true. We had good and stable jobs with high incomes.”

For Susan, it was very clear from the start that she was going to join the strike; she had been an avid opponent of the Chávez regime from the start. “I was probably on the list as soon as they started compiling them,” she says.

For a little while, Jennifer was not sure what to do because she cared about the company and the foreseeable future. She felt intimidated. But when a peaceful protest ended up in a massacre, instigated by Chávez, she firmly decided to join the strike that started in December 2002.

But did the strikes have any effect? “No,” says Susan, “rather the opposite.”

Rather than listening to the demands and concerns of the workers, Chávez would hold speeches on TV, called “Aló Presidente” during which he would fire PVDSA managers on the spot, by blowing a whistle, naming someone and saying, “You’re fired!”

Others were put on a list that was published in the national newspaper. Susan remembers the day in February 2003 when she found out about her redundancy. “They put me and about 1,600 colleagues from INTEVEP up for dismissal in one go.”

It was bitter, obviously, also because there was no compensation paid, and people’s pension contributions were also stolen. “For me,” says Susan, “it was not too big a deal, as I was at the start of my career, but for others who were more senior, it was devastating.”

Ecopetrol in Colombia said Thank You Chávez – we don’t need to train these people who are now happily coming to work for us

At the end of the day 18,000 people were fired over a period of five months. Jennifer was part of that group too. And who replaced all those people who were let go? Obviously, people who supported Chávez first of all, who supported “El Proceso”, the process. “Not the brightest cookies in the jar,” says Jennifer. “Many of them had been studying for 12 years and had never shown much ambition.”

In parallel, managerial positions also went to people who were loyal to Chávez; having a background in the company did not matter anymore, as was the case before.

So, was PDVSA a company based on the values of working hard before, after the Chávez takeover, this philosophy went out of the window. “We used to be a company based on meritocratic values,” said Susan.

Knowing that the company employed around 40,000 people at the time and knowing that it was mostly technical people who were made redundant, there is a very clear indication as to why oil production was to drop.

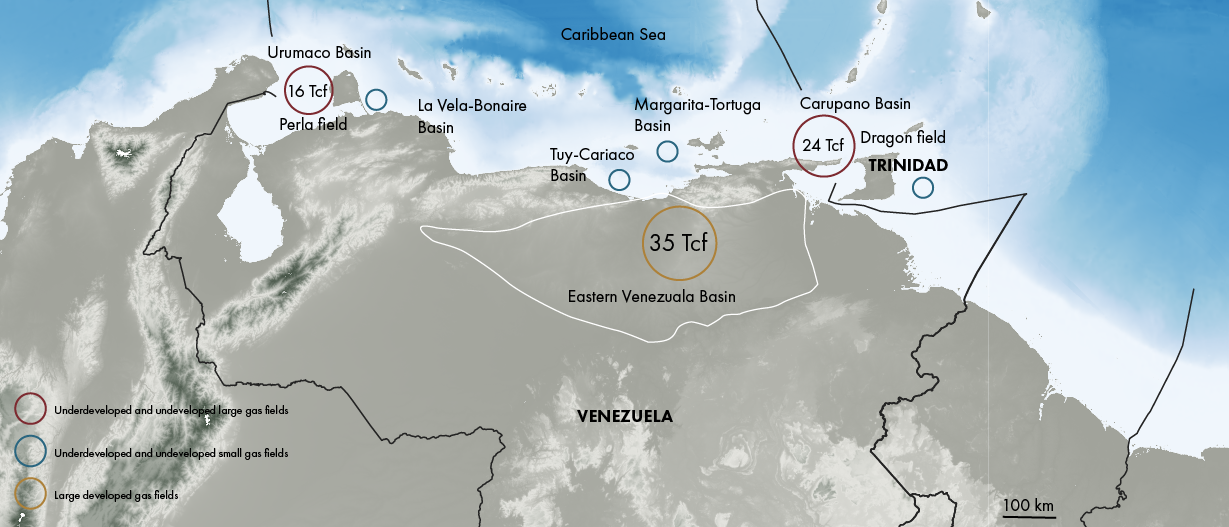

It is against this backdrop that it becomes easier to understand why so many people were happy with Saturday’s events, even when there is absolutely no clear path to an immediate turn of the industry. “At the end of the day,” Jennifer said, “it is the Chinese and the Russians who are now the owners of a lot of the oil-producing assets. They won’t leave by the clip of a finger.”

But regardless, there is a flicker of hope again. For some, there may be hopes of returning, but let’s not forget how many saw their opportunities squashed and were unable to move abroad and start a new career. They not only lost their jobs, but their pension, savings and futures were stolen at the same time.