As Paul de Leeuw from Robert Gordon University noted during the panel session at a Westwood Energy event in Aberdeen last week: “Before the COP26 Conference in Glasgow, new oil and gas developments could not be discussed in the UK. Only a few months later, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the narrative changed dramatically with all the emphasis placed on security of supply.”

What will the talk of the town be in half a year? Nobody knows, but what is apparent is that the applications NSTA received for the latest and 33rd petroleum exploration licensing round would probably have looked very differently if recent historic events had unfolded in another way.

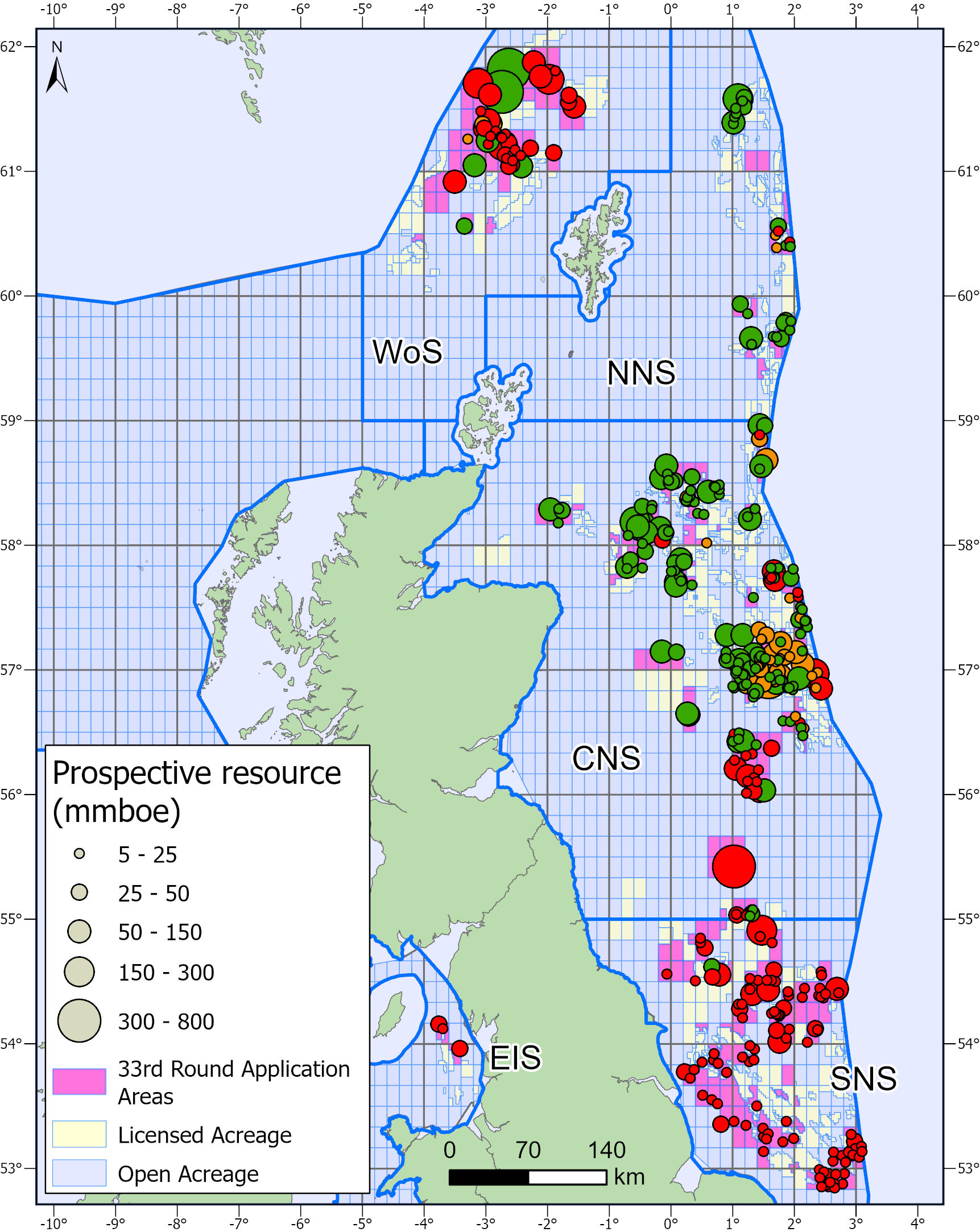

Documents made available by the UK government show that the main areas where applications were filed are the West of Shetlands (WOS) and the Southern North Sea (SNS). If one would only look at which part of the UK Continental Shelf holds the most prospective resources, the focus on WOS and SNS seems odd at first.

Namely, Westwood estimates that it is the Central North Sea that holds the most potential by far – around 5 billion barrels of risked potential resources. However, the Central North Sea is dominated by oil prospects, whilst the SNS is mostly gas, and it is probably for that reason that companies are flocking to the very part of the continental shelf that only a few years ago seemed to be amongst the quietest on the UKCS.

Even though the West of Shetland does hold more oil than gas prospective volumes, there is a good number of sizeable gas prospects in this relatively unexplored part of the UKCS, and that is probably the reason why so many applications were filed there.

The infrastructure setting in the West of Shetland is entirely different from the SNS though, with the latter still having a relatively dense network of pipelines in shallow water whilst the West of Shetland is in deeper water – beyond jack-up territory – and has less infrastructure, especially for gas. Hence the need for bigger finds in the north.

A bumper year?

But how has exploration fared so far this year in the UK? Looking back over the past 10 years, results for 2023 have been quite good, bearing in mind that the reserve replacement ratio is still very poor in the best of times at around 15%.

In two ways, 2013 and 2023 are the most contrasting years of the last decade, as technical manager Alyson Harding showed. Ten years ago, 21 exploration wells were drilled on the UKCS. However, none of these resulted in a commercial discovery, meaning that not a single barrel was added to the resource base.

This year, even with a few months and a few well results still to be announced, the discovered resource stands at 130 MMboe thanks to success at Pensacola (99 MMboe) and Orlov (30 MMboe). This means that 2023 is surely the most successful year for exploration across the UKCS in the last decade.

And, 2023 has the potential to become a real bumper year if the Devil’s Hole Horst well comes in as anticipated. Unfortunately, the driver behind drilling this potentially massive Zechstein prospect is not with us anymore – Niels Arveschoug passed away earlier this year – but the 584 MMboe prospect has the potential to shake up the UK’s replacement ratio once more and also ensure that it is oil that dominates the charts and not the gas that seems so much in favour at the moment.