On a rainy day in March, on a quiet countryside road north of the village of Ellon in Aberdeenshire, northeast Scotland, I am welcomed by geologist Drew Craig from Aberdeen Minerals. We are to visit the site where his company is drilling a number of exploratory boreholes to sample a mineral deposit that may host economic quantities of nickel and copper.

This place has been on the radar of the mining industry for a while. “Ever since a local farmer spotted that his crop of turnips – a Scottish delicacy – experienced suboptimal growing conditions and had some ground samples tested, it has been known that anomalous concentrations of nickel are the root cause of the issue”, Drew says.

The companies that initially came to the area following the discovery of metals close to surface also had core samples taken. However, the quality of the material and the reliability of the analyses prompted Aberdeen Minerals to embark on a new drilling campaign. “The reporting standards for mineral deposits are very strict and to move a site up the ladder from a prospective deposit to a commercially viable mine one needs to comply with very stringent rules of reporting and sampling”, Drew explained later during the visit.

Promising results

In June, the company announced positive results from their campaign that entailed drilling of seven boreholes to a maximum depth of 400 m. Fraser Gardiner, Chief Executive Officer of Aberdeen Minerals, commented: “Our maiden drilling programme at Arthrath has been a resounding success. The levels of mineralisation have exceeded our expectations and we are strongly encouraged by the evidence supporting an exploration model of increasing sulphides and corresponding metal grades at depth. It is now apparent that historical drilling only scratched the surface which makes us very excited about the mineral potential at the project and surrounding district.”

In contrast to oil and gas wells, the boreholes drilled here have a 45 degrees angle from the start. It is done to ensure maximum exposure to the Ordovician dyke that dips in an opposite direction.

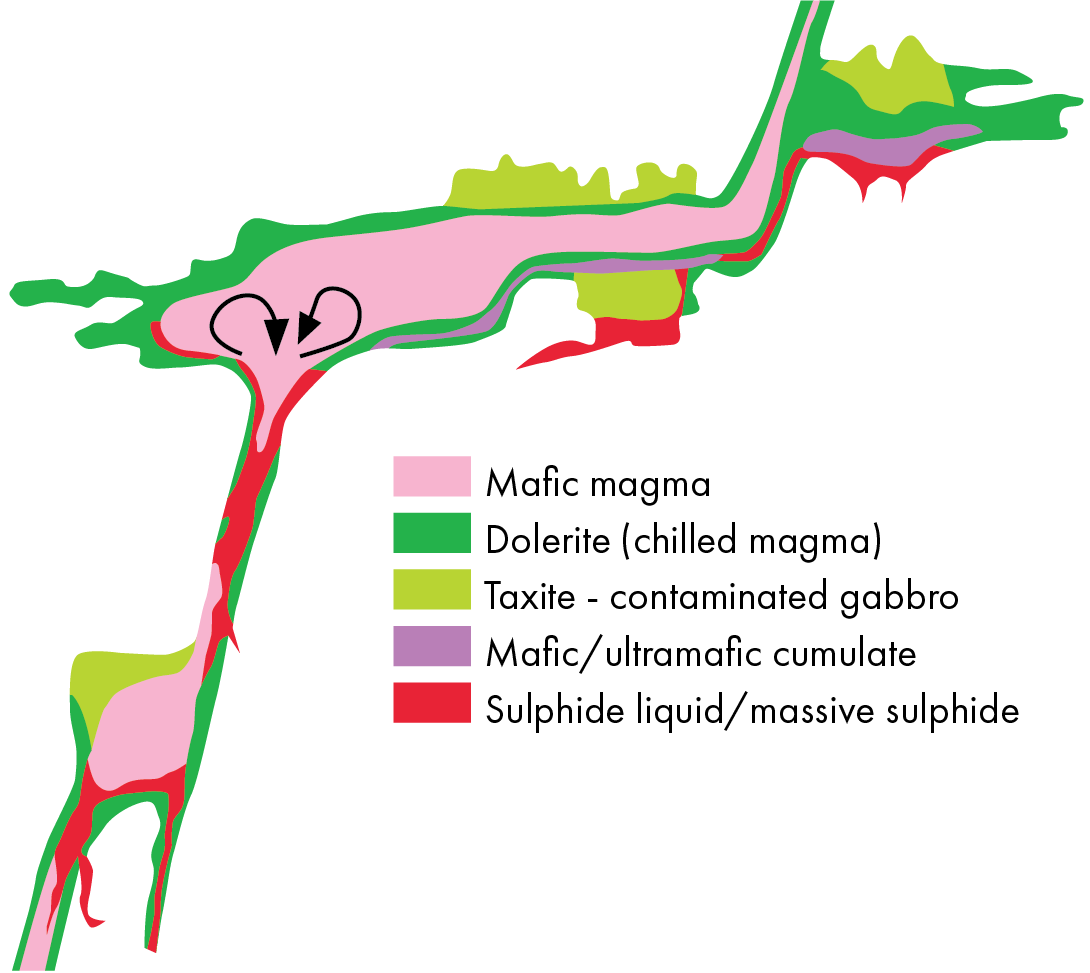

Previous models of the mineral deposits in the area assumed that they had formed as a result of gravitational settling of sulphide deposits within layered intrusions into the Dalradian host rocks. The current model favoured by Aberdeen Minerals is one of a conduit-style magmatic sulphide, as the figure here further illustrates. One of the mechanisms through which enrichment in sulphides takes place is the settling of these minerals when a magma reaches a larger space where it loses momentum.

Apart from the area north of Ellon, the company has also carried out airborne surveys to map larger areas of northeast Scotland for the presence of other magmatic bodies.

It is an interesting thought that the oil industry settled down in an area characteristic of its granites, gneiss and intrusions. Will the geology of Aberdeen become key to its future again, similar to the times when the city was a major exporter of granite?