Many people think that heavy oil developments are even worse than lignite, but that is not the case according to Maurice Bamford who recently gave a talk on the Pilot heavy oil discovery in the UKCS.

“Yes, there is more asphalt and petroleum coke in the heavy oil, but it is these ingredients, along with the additional lubricants, that are required for materials needed in the energy transition”, Maurice said. Also, based on the current development concept that includes a wind turbine for powering offshore installations and a polymer flood strategy, the project ranks amongst the 5% lowest in terms of emissions of CO2 per produced barrel. The polymer flooding approach strongly reduces the economic lifetime of the field, which means that the tail end of production, where emissions are usually at their highest, is much shorter.

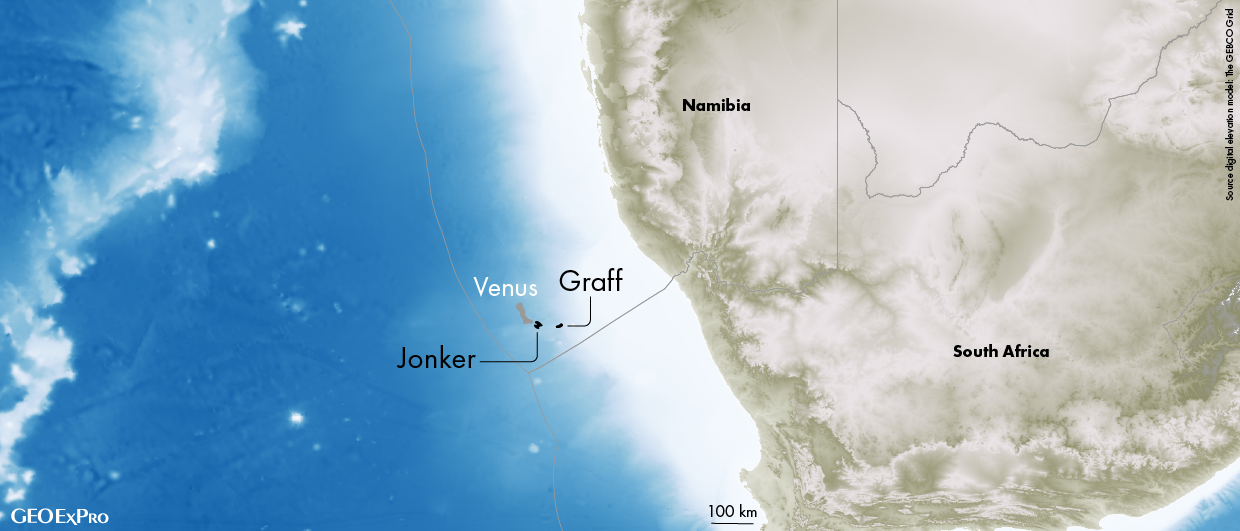

Pilot is not new, being discovered in 1989 by PetroFina. It has multiple appraisal penetrations and has been subsequently held by a handful of different companies. As such, the current operator Orcadian Energy regards the discovery fully appraised and ready for development given current technology. The estimated volume of recoverable oil is now sitting at around 95 million barrels.

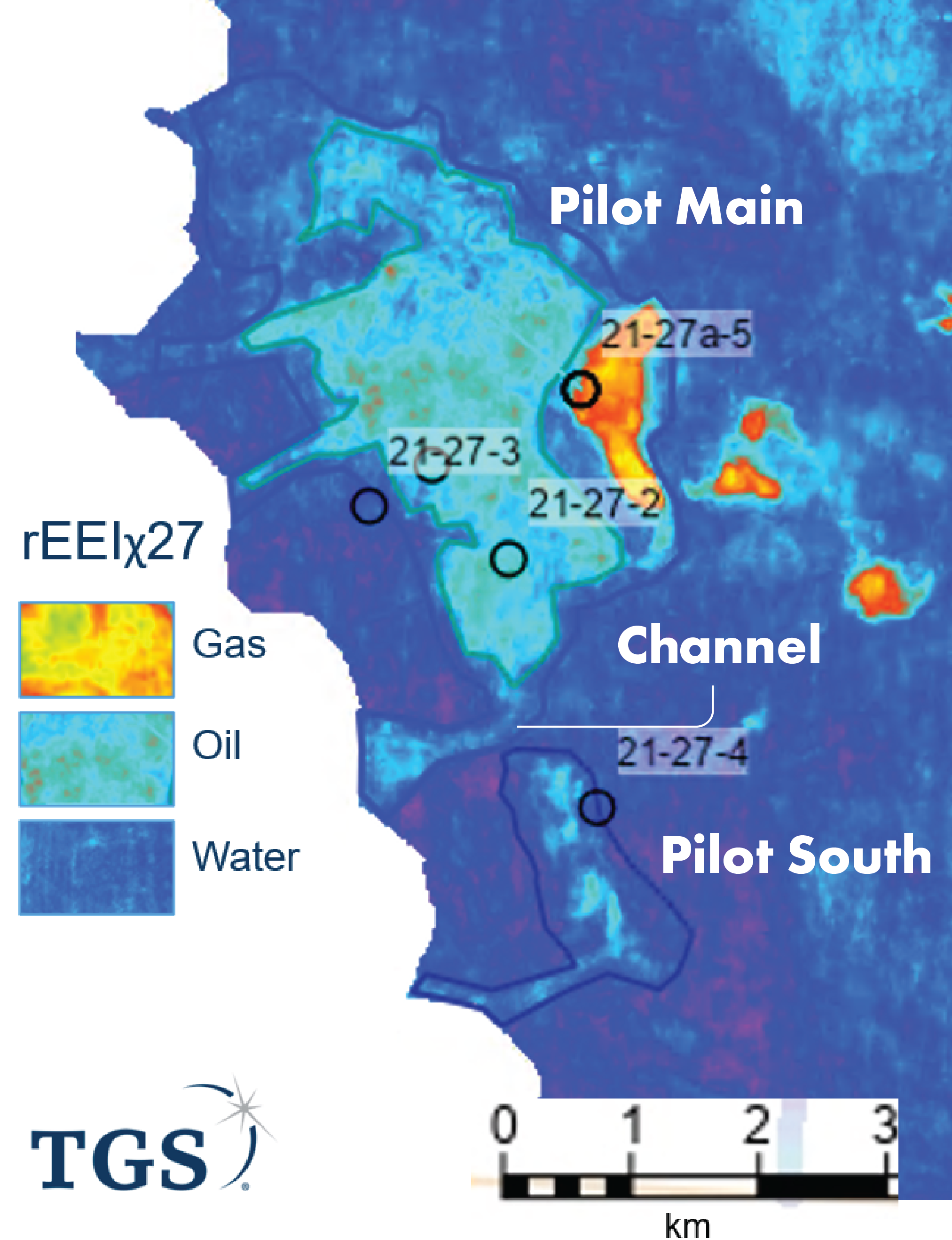

The Pilot reservoir is a relatively extensive amalgamated sand sheet consisting of clean sandstones that were deposited as a lowstand deposit at the foot of the Mousa delta in Eocene times. The seismic section above nicely shows the clinoforms of the delta. However, the architecture of the reservoir is not a simple basin-floor lobe. Depositional patterns suggest powerful erosive turbiditic currents that entered the basin via multiple feeder channels and underwent reflection and refraction within a ponded basin, as Maurice explained during his talk.

The reservoir that is also a seal

The map shows that the main Pilot field is bordered by a smaller oil accumulation, Pilot South. Based on well and seismic data, the identical sands of both fields look to be connected. The only “disruption” is caused by a channel that fed the sands into the sub-basin and beyond, but given that this element also has an oil-filled sand response on the seismic inversion map, it is difficult to explain the 30 m difference in oil-water contact between the two fields.

“Our explanation”, said Maurice, “includes a muddy lag on the southern side of the channel.” This can be seen on the seismic inversion map as a break between the channel and Pilot South. One possible explanation for this could be contour parallel currents depositing fines on the southern margin of the feeder channel, which subsequently formed a barrier for the migrating oil. “It doesn’t have to be a 100% seal, as the oil is heavy and we know there is significant leakage from the widespread paleo-oil column.