South Africa has already astonished the world with its recent discovery of large volumes of gas condensate in its southern Outeniqua Basin. Now, the Orange Basin is poised to erupt as the world’s next exploration hotspot with the drilling of two new paradigm-changing deepwater plays. These two wells are being drilled late in 2021 in Namibia by the border with South Africa. If either is successful, the on-trend extension of these plays will decisively confirm southern Africa’s rightful place in the spotlight of the exploration community.

The Graff-1 and Venus-1 wells, located on adjacent acreage, will be operated by Shell and TotalEnergies respectively and represent a culmination of exploration efforts that were sparked into life by the results of three deepwater wells drilled in Namibia by HRT in 2013. Each of these wells encountered thick, mature Aptian source rocks, and in one case recovered light oil to surface, proving the northern extension of this source rock system which had previously been encountered in the southern margins of the Orange Basin by DSDP well 361. The HRT wells (Wingat-1, Murombe-1, and Moosehead-1) have gone down in exploration folklore for their bravery in proving the existence of the important ‘source rock’ piece of the exploration jigsaw. Whilst this is one part of the hydrocarbon system that is associated with the earliest moments of the opening of the Atlantic – next the reservoir and trap need to be proven as well. The legacy of the HRT wells was that the industry saw that with a thicker overburden than that encountered at the DSDP 361 location, this source will be an effective generator of oil, ushering in a race to find the final pieces in this puzzle: the wells where all the hard-won elements of the hydrocarbon system come together.

The Graff-1 and Venus-1 wells, located on adjacent acreage, will be operated by Shell and TotalEnergies respectively and represent a culmination of exploration efforts that were sparked into life by the results of three deepwater wells drilled in Namibia by HRT in 2013. Each of these wells encountered thick, mature Aptian source rocks, and in one case recovered light oil to surface, proving the northern extension of this source rock system which had previously been encountered in the southern margins of the Orange Basin by DSDP well 361. The HRT wells (Wingat-1, Murombe-1, and Moosehead-1) have gone down in exploration folklore for their bravery in proving the existence of the important ‘source rock’ piece of the exploration jigsaw. Whilst this is one part of the hydrocarbon system that is associated with the earliest moments of the opening of the Atlantic – next the reservoir and trap need to be proven as well. The legacy of the HRT wells was that the industry saw that with a thicker overburden than that encountered at the DSDP 361 location, this source will be an effective generator of oil, ushering in a race to find the final pieces in this puzzle: the wells where all the hard-won elements of the hydrocarbon system come together.

Source Rocks Provide the Key

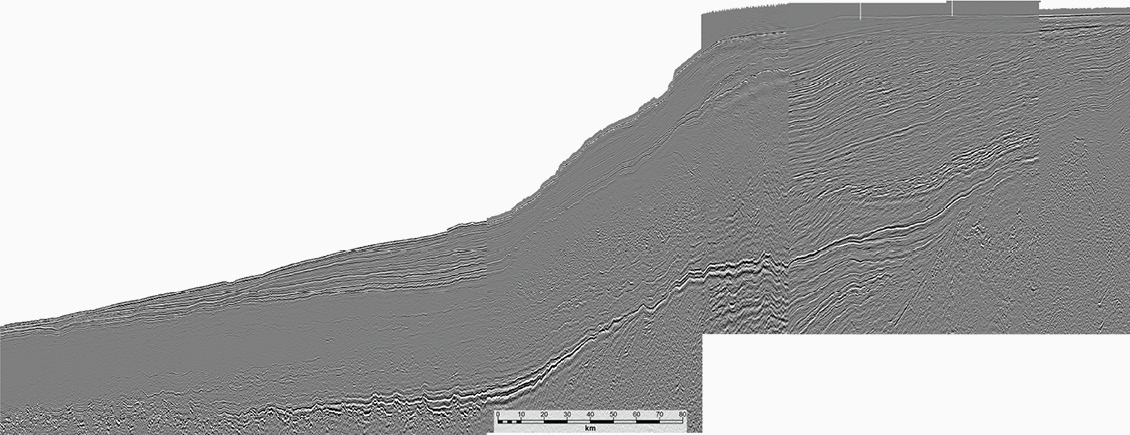

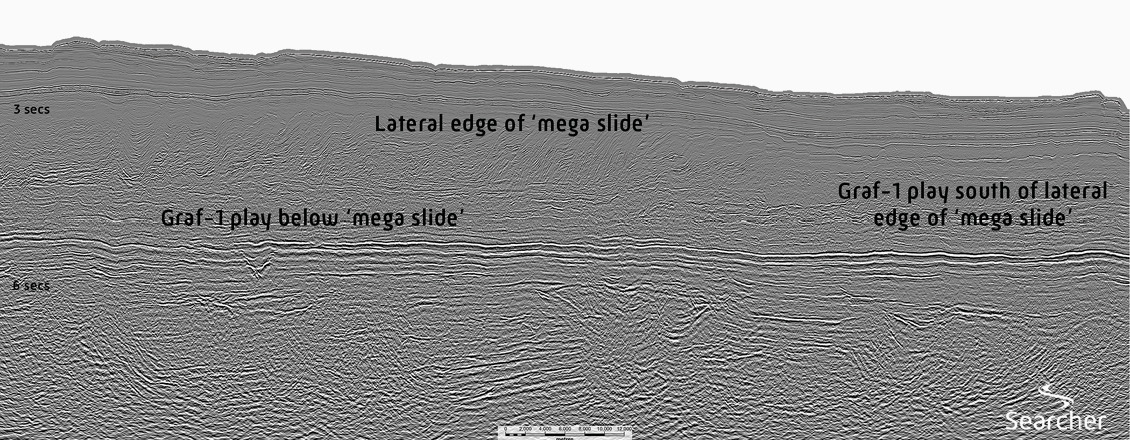

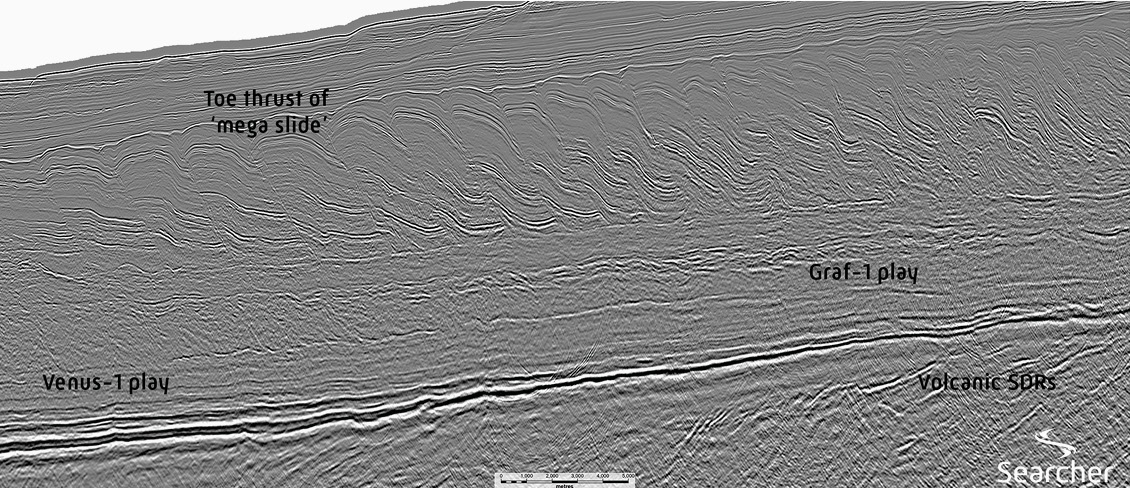

The Aptian source rock can be mapped on a regional grid of modern 2D seismic data that extends from the Luderitz Basin of Namibia to the Orange Basin’s southern margin in South Africa. Like many ‘magma rich’ passive margins, the crustal architecture of this margin changes as you move offshore. This transformation is from a rifted crust which becomes more and more dominated by volcanic lava flows which were erupted as the Atlantic opened and formed an outer, high feature before turning into true oceanic crust (Figures 1 and 2). The Aptian source deposited on either side of this high has a characteristic seismic response – a soft top associated with a decrease in acoustic impedance and a hard base with a low frequency character, associated with a Type-IV AVO anomaly Eastwell et al., 2018; Davidson et al., 2018). With confidence in the source rock much higher, each of the imminent wells, Graff and Venus, will target different reservoir/trap pairs, to clarify what play combination is effective on this margin. Graff-1 will target a Late Aptian/Albian sandy slope hybrid turbidite contourite channel system and Venus-1 will target slightly older sands, in an Aptian base of slope/fan setting. Both targets appear to have an element of stratigraphic trapping.

Graff-1 lies within the slope setting, down-dip of a stratigraphic trap. The trap is formed where sands are not deposited (a bypass zone) or subsequently eroded creating a break in the migration route for oil as it tries to escape out of the basin. When the oil cannot bridge this break or gap, it is left effectively stuck down-dip and trapped in the prospect. Figures 1 and 3 show a West–East seismic dip-line from the South African Orange Basin close to the Namibian border, with analogue positions of the Graff-1 and Venus-1 plays indicated. Figure 3 shows a strike line running from the Namibian border over the extension to the Graff play in South Africa. These also show the extraordinary Orange Basin ‘megaslide’ that sits right above the slope play. The dip line is familiar (for example De Vera et al., 2010) but the strike line shows the lateral toe thrusts of this gravity collapse feature. This megaslide has long captivated geoscientists as it demonstrates the extreme instability of this margin in the Latest Cretaceous. Actually, all through the Late Cretaceous this margin became even more unstable, evidenced by basinal mass transport systems, as the continent of Africa slid across a complex net of upper mantle convection cells (Hodgson and Rodriguez 2017; 2018). The megaslide, formed by a gentle slow collapse of the shelf, is ironically an indication that the instability was drawing to a close.

Slope bypass as a trapping mechanism is very hard to nail down on seismic – as a thief zone would be at a sub-seismic scale, yet a characteristic of the seismic response from the Graff sands indicates the presence of oil or gas, so hopes are running high. A similar style of slope channels with encouraging seismic responses has led to the multiple and repeated success seen offshore Guyana and Suriname. Just a few years ago, that play was considered uncertain with unproven source and trapping style. With the right regional bypass system – extraordinary repeatability will follow a ‘play-making’ well. Venus-1 also requires an up-dip stratigraphic trap – yet this prospect is even more ground-breaking as it targets sands deposited on the basin floor out beyond the volcanic ‘outer high’. The industry has wanted to explore the basin floor fan plays of the Atlantic for many years; for it is on the basin floor that the traps become truly big, and Venus is no exception, yet only recently has technology allowed deepwater drilling to target this setting. The upward convecting parts of the net of mantle cells that caused the shelf instability at the end of the Cretaceous is also responsible for lifting basin floor fans sitting on Oceanic Crust into drillable water depths. Recently, huge discoveries in similar settings in Senegal and Mauritania have been in uplifted basin floor fans of this type. The Venus prospect too, has an encouraging seismic character that indicates hydrocarbons at the prospect crest, whilst this character switches off at the spill point; a very significant observation that provides a lot of confidence that this well will be successful. Success here will invigorate ‘Atlantic opening plays’ on both margins – from Sergipe to Pelotas in the west and Cameroon to Cape Town.

Drilling Success Will Flow South

Whilst these two wells will be drilled in Namibian waters, should either of the plays be successful, the acreage to the south in South Africa will become white hot with interest. The play is predicated on the Aptian source rock extending to the south and sand equivalents of either the Graff or Venus plays are also evident on the available 2D regional grids.

To facilitate the investigation of the distribution of plays and traps in South Africa’s Orange Basin, Searcher has built a subscription-accessed cloud-based review and delivery system in South Africa of >100,000 line km of legacy 2D data (examples in Figures 1 and 2). This dataset is adequate for preliminary exploration analysis – basin modelling, isopach and play fairway building, but Searcher want to help refine this analysis more and so are currently reprocessing a selection of these legacy lines. These data are focused on generating a dataset that will allow extrapolation of the Graff and Venus plays, into South Africa. Searcher will also add to these data in the next seismic acquisition season, by collecting over 20,000 km of new long streamer, deghosted 2D data. This will allow the results from drilling in Namibia to be fully integrated into the geological understanding of the southern Orange Basin.

With each well drilled in the deepwater of Namibia and South Africa we have moved closer to removing the uncertainties that surround the exploration jigsaw puzzle. After the HRT wells we could see for the first time the picture on the ‘exploration puzzle box’ and with these next two wells we will see which reservoir/trap pair will fit with the source rock (or perhaps both will!). Following the example of the Liza discovery in Guyana it is clear that deepwater discoveries are best monetised quickly, so it is expected that success will ignite a surge of activity over the next five years with a string of follow-on exploration interest, to indeed rival the activity that Guyana and Suriname have experienced in the last five years. Good geoscience and ‘brave wells’ have led the way to the start of this race; now it is time to settle into the blocks, get under starter’s orders – and we’re off!

References

Eastwell, D., Hodgson, N.A. and Rodriguez, K. Nov 2018. Source rock characterization in frontier basins. First Break, 36, pp.53–60.

Davidson, I., Rodriguez, K. and Eastwell, D. 2018. Seismic detection of source rocks. GEO ExPro, 15(6), pp.20–23.

Hodgson, N.A. and Rodriguez, K. March 2017. Shelf stability and mantle convection on Africa’s passive margins (Part 1). First Break, 35, pp.93–97.

Hodgson, N.A. and Rodriguez, K. Feb 2018. Towards a global tectonic model: A new hope. First Break, 36, pp.77–80.

De Vera, J., Pablo Granado, P. and McClay, K. 2010. Structural evolution of the Orange Basin gravity-driven system, offshore Namibia. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 27(1), pp.223–237.