On the North Slope’s National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska, or NPRA, a ‘land rush’ was expected during an early 2021 federal lease sale, as described by Senior Research Geologist, David Houseknecht of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Of the 18 million acres made available for the sale by the Trump administration, 7 million included the highly prospective Teshekpuk Lake area, acreage that has rarely or never been leased.

However, all came to a halt in January when the Biden administration, known for its adverse attitude toward the industry, swooped in and suspended all lease sales on federal land for further review.

While that move was expected, it has made many question the fate of NPRA and, in a much broader context, how a strategic shutdown of oil and gas projects and infrastructure, such as the Keystone XL pipeline, will ultimately affect the country.

New Life on the North Slope

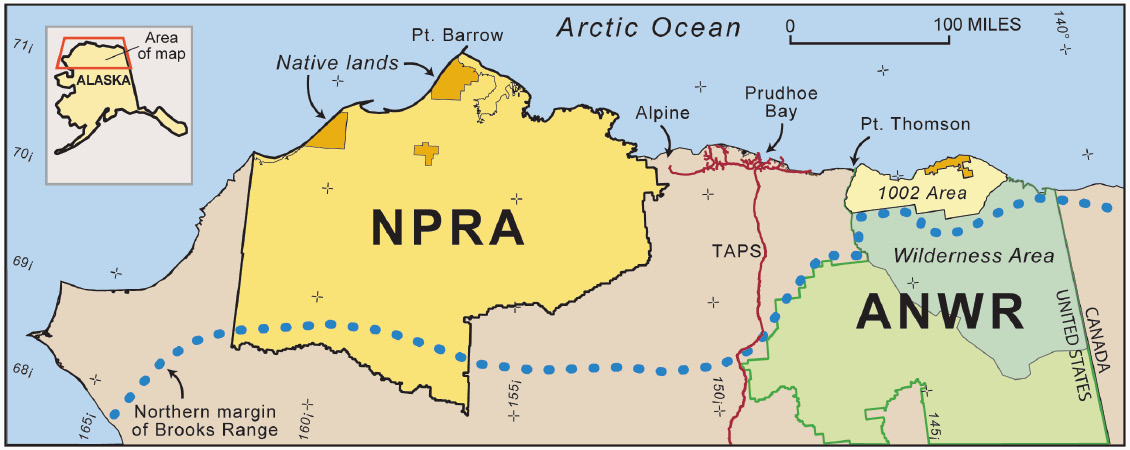

They may be in a remote, often forgotten part of the world, but operators on Alaska’s North Slope reclaimed center stage after a recent series of significant discoveries, both in and adjacent to NPRA. NPRA is a 23 million-acre site set aside by the federal government a century ago for its known petroleum value (and modified in 1976 to protect environmentally sensitive areas, such as Teshekpuk Lake).

After the excitement from the historic discoveries of Prudhoe Bay in 1968 and the Alpine Field in 1994 subsided, the North Slope remained relatively quiet for nearly two decades until new discoveries were made in stratigraphic traps in the Cretaceous Nanushuk and Torok Formations.

In 2013, Armstrong Energy and Repsol announced 1.2 billion barrels of recoverable oil from its Pikka discovery, just to the east of NPRA. That was followed by ConocoPhillips’ 2016 Willow discovery in NPRA, which is thought to contain up to 750 million barrels of recoverable oil.

The USGS immediately updated its assessment of the North Slope’s resources in the Cretaceous Nanushuk and Torok Formations, including state waters and NPRA. In 2017, it estimated that there were mean undiscovered, technically recoverable resources of 8.7 billion barrels of oil and 25 Tcf of natural gas. According to the assessment, the estimates are “significantly higher than previous estimates, owing primarily to recent, larger-than-anticipated oil discoveries.”

Essentially, prospective acreage in northern NPRA extends across 400 kilometers from east to west, Houseknecht said.

Buoyed by the possibilities, lease sales on the North Slope, in particular NPRA, soared, bringing in $11 million in 2019, a steep jump from the $1.5 and $1.1 million raised in 2018 and 2017, respectively.

The 2021 sale was expected to be even more lucrative with the inclusion of areas near Teshekpuk Lake.

With the Pikka and Willow discoveries to its south-east and known oil seeps from the Nanushuk Formation to its north-west, the Teshekpuk Lake area is no doubt in the middle of a major hydrocarbon fairway. Yet, it has been designated a ‘Special Area’ by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management because it is a critical breeding ground for migratory birds, a calving area for caribou and the largest lake in Arctic Alaska that allows for fishing in winter months.

Many conservation groups believe this land should remain off limits. “There are some places in NPRA that have globally significant ecological values and are culturally irreplaceable,” said David Krause, assistant director of The Wilderness Society in Alaska. “None of Teshekpuk Lake Special Area should be leased.”

In addition to the Teshekpuk Lake area, about 6 million acres in western NPRA, also included in the 2021 lease sale, are now thought to be prospective, and operators are hungry to acquire its acreage.

“Seismic data across the entire North Slope and western NPRA shows the potential for new resources, said Renee Hannon, a consultant and former Alaska Onshore Exploration and Geoscience manager for ConocoPhillips from 2000–2017. “The Pikka and Willow fields contain shallow marine sandstone, good reservoir properties, good flow rates, are at reasonable depths, and contain light oil,” she added. Both are located near existing infrastructure and will ultimately feed into the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, or TAPS. “This is why people are so excited,” Hannon explained.

“I wouldn’t be surprised to see additional discoveries in the Willow to Pikka size range,” Houseknecht said. “There are many, many, many anomalies in seismic data just like those associated with Willow and Pikka that have not been tested.”

Benefits to Alaska

While the jury is out on whether the lease sale will move forward, be scaled back or canceled, any pullback would impact Alaska.

“Our state’s economy and infrastructure depend on new, producing fields to offset the decline of older fields,” explained Sean Clifton, Policy and Program specialist for the Alaska Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Oil and Gas. “Without development of new North Slope fields, throughput in TAPS could drop low enough that the pipeline may have to shut down.”

Once in production, the Pikka and Willow discoveries will account for roughly 45% of total Alaska production, keeping flow rates steady at roughly 500,000 barrels a day. Without them, volumes are expected to drop by half by 2030.

“We need the inertia of activity across the North Slope, including federal lands, to continue that development that gets oil in the pipeline, gives people jobs and keeps us growing,” Clifton said.

“While oil has generated up to 90% of the state’s unrestricted revenue in the past, low oil prices and declining production mean oil is projected to provide between 19 and 22% of unrestricted revenue over the next decade,” he added.

When you factor in pilots, mechanics, truck drivers and cooks, Clifton said, “just about everything that everyone does in this state ties into the oil and gas business.”

The Willow discovery is expected to create 2,000 construction jobs, 300 permanent jobs, and generate more than $10 billion in federal, state, and North Slope Borough revenue.

“The Pikka discovery is expected to create a similar number of jobs and revenue,” Hannon said.

“When you start canceling lease sales or removing acreage, not only do you stop exploration, you stop innovation for developing newly discovered resources,” she added. “And because there is such a long lead time between discovery and first oil, this is when you risk stranding these discovered resources because you may not get them into TAPS.”

According to some estimates, the North Slope and offshore Arctic region still hold 50 billion barrels of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil.

A Troublesome Transition

While Alaska might be one of the first states to feel the effects of the new administration’s stance on the industry, a ripple effect is no doubt coming.

If leasing is in question now, permits will be next, said Mark Myers, former commissioner of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources and former USGS director. As the Arctic continues to warm, Alaska will continue to see dramatic changes in landscape, including erosion along its northern coast, thawing permafrost and a change in vegetation. All are likely to affect how, if and when industry-related activities are permitted. “These changes will affect views on lease sales,” Myers said.

If the 2021 NPRA lease sale is canceled, that sends a mighty message: “This is particularly important because it is not ANWR (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge), it is not offshore. It is an onshore petroleum reserve,” Myers said. “When you pull that out of leasing, you are making a different statement. Not that you are worried about the Chukchi Sea or licensing in ANWR, it’s a strong signal that they are going to pull back altogether on leasing in federal lands.”

If that is the first step in distancing the nation from oil and gas as the new administration looks to renewables, what does that plan look like?

While Myers can see oil give way to natural gas as a transition fuel and renewables become greater suppliers of electricity generation and transportation fuel, there are missing links on the transition trail, namely the need for energy storage and distribution lines, and both will have environmental consequences.

For example, energy storage requires the mining of lithium and other critical minerals for batteries, and transmission lines will no doubt cross environmentally sensitive areas and habitats all over the country, including federal lands, he said.

Point of No Return

“The surface disturbance directly caused in creating the infrastructure needed for a complete transition to renewable energy could potentially be larger than that currently used in the production and transportation of fossil fuels. Federal lands will play a major role in the transition,” Myers said. “ Are we willing to accept more surface environmental degradation on our public lands from renewables because they decrease our dependency on fossil fuels and lower greenhouse gas emissions? It will be interesting to see how the government will make land-use decisions.”

Myers embraces a transition to sustainable energy as long as a viable plan is mapped out.

“If you don’t allow development or permitting of oil and gas on federal lands anymore, you are making a statement that we are at the point of no return,” he said.

If projects to explore for and transport oil and gas are systematically shut down, Myers said the country is essentially playing a game of Jenga. “When you start pulling pieces out,” he asks, “are you going to collapse your structure?”