As the surge of oil and gas exploration activity on the African continent continues apace, a clutch of countries, including Mauritania, are emerging as particular hot-spots on a continent filled with resource potential. The offshore Chinguetti oil discovery in 2001, and the subsequent Banda, Tiof and Tevet Miocene discoveries, all made in the period to 2003, raised the country’s hopes for oil wealth, paving the way for the creation of a favourable environment for rapid offshore oil development and the creation of an offshore oil boom. Fiscal changes, however, have yet to be realised and production has failed to meet initial expectations. Similarly, after nearly four decades of inactivity, exploration of the Taoudeni Basin in the innermost part of the country has yet to spark industry interest, and consequently large portions of onshore acreage remain unexplored.

However, hopes have been very much revived, particularly offshore, by Kosmos’s recent gas discovery in deepwater Block C8, again hinting that Mauritania could become a global energy player.

Emerging Deepwater Potential

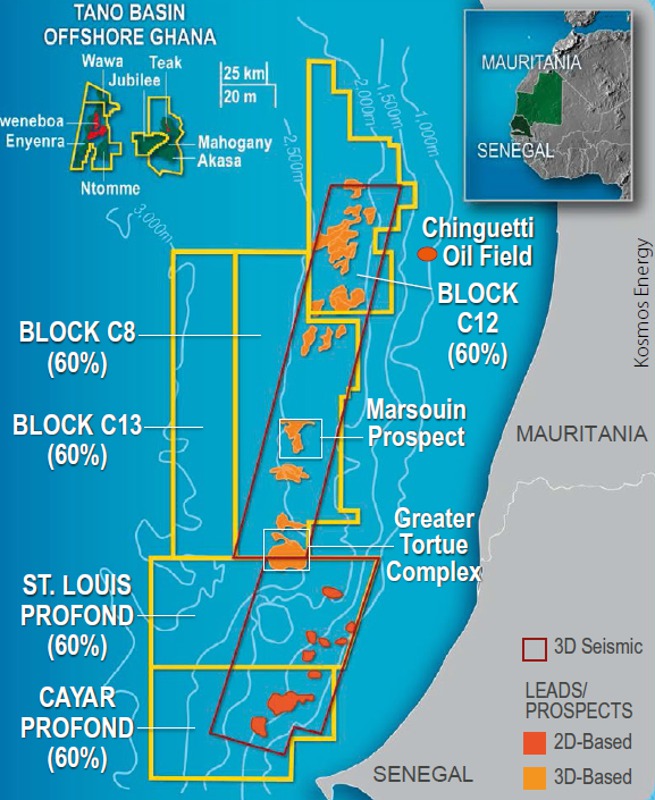

Offshore Mauritania. (Source: Modified from Kosmos Energy)The country is a hydrocarbon wildcard in the truest sense, as little is known about its real potential either on or offshore and there is a poorly established international industry presence. Chinguetti was an important milestone, but having started up in 2006, it is still the country’s only producing project. Unspecified technical issues led to a drastic decline in production rates, tumbling from an initial 60,000 bopd to just 20,000 bopd within 10 months, and further slides have brought rates down to less than 9,000 bopd more recently. Similarly, the field’s proven and probable reserves have been consistently revised downwards from the original estimate of 120 MMb to just 34 MMb.

Offshore Mauritania. (Source: Modified from Kosmos Energy)The country is a hydrocarbon wildcard in the truest sense, as little is known about its real potential either on or offshore and there is a poorly established international industry presence. Chinguetti was an important milestone, but having started up in 2006, it is still the country’s only producing project. Unspecified technical issues led to a drastic decline in production rates, tumbling from an initial 60,000 bopd to just 20,000 bopd within 10 months, and further slides have brought rates down to less than 9,000 bopd more recently. Similarly, the field’s proven and probable reserves have been consistently revised downwards from the original estimate of 120 MMb to just 34 MMb.

Problems aside, Chinguetti elevated the deepwater portion of the Mauritania-Senegal-Gambia-Bissau- Conarky Basin from its former rank wildcat virgin frontier status, putting it on the map as an exciting potential new deepwater province and opening up much of the north-west quarter of the continent. Despite Chinguetti’s disappointing performance and chequered history, Mauritania’s unexplored expanses leave plenty of room for lucrative new discoveries.

While the majority of the offshore, nearly 116,000 km2, remains unlicensed, two companies, Tullow Oil and Kosmos Energy, head up a handful of companies exploring there. As with most extensive frontier exploration projects, Tullow encountered disappointments; the much-anticipated Fregate-1 wildcat in Block 7, while confirming the potential of the Late Cretaceous turbidite reservoirs, was not commercial but again teased at the potential of large offshore reserves. The company planned an aggressive four-well exploration campaign but with the falling oil price, corporate focus is now shifting to lower cost exploration in East Africa and Norway.

Tullow operated the 1 Tcf Banda gas field, the development of which forms part of the larger Banda Gas to Power project, which envisaged supplying electricity within Mauritania and to Senegal and Mali, with the Banda field contributing 65 MMcfgpd for 20 years. However, the project, which was to have produced first gas mid-2016, appears to be another casualty of the low oil price environment, with the government struggling to revive interest following Tullow’s withdrawal.

Kosmos currently holds the exploration baton, the company’s chairman and CEO Andrew Inglis claiming “our Tortue 1 gas discovery in Block C8 is the industry’s largest offshore find so far this year.” The company holds three contiguous deepwater blocks that include the outboard fairway of the underexplored Upper Cretaceous stratigraphic play concept, the company’s core exploration theme. Kosmos estimates that the field, renamed Ahmeyin, has a mean resource of 8 Tcf subject to an appraisal programme, which will get underway after the Marsouin 1 wildcat in the central part of Block C8, which is expected to spud shortly.

High Risk – High Reward

The potential for commercial hydrocarbons is significant, but risks from poor infrastructure, a changeable political landscape and significant technical/financial challenges make it far from a sure bet. Nevertheless, companies investing in Mauritania’s nascent offshore sector are confident that the finds will come, and their success could bring energy independence and accelerated economic development to a country whose population desperately needs it.