Through the windows of the chemistry lab at the University of Colorado in April of 1954, sophomore Gil Mull gazed out at the Flatirons, admiring their beauty and mystique. As the odours of the smelly lab wafted through the air, Mull realised that he really belonged outside, and to get there he needed to change his major to geology.

That change in track eventually took Mull to Alaska to map in the Brooks Range and, in a serendipitous chain of events, put him at the historical well that first tapped North America’s most prolific petroleum reservoir at Prudhoe Bay.

His astute observations in the field and experience as a wellsite geologist paved an upwardly mobile path for Mull that pointed toward a comfortable office in a skyscraper, rather than months living in 2.5-by-3m canvas tents. But he did not take that path.

After the swells of excitement from the Prudhoe Bay discovery subsided, Mull retreated to the hills of the Brooks Range and the North Slope to continue mapping projects that took him from the Canadian border to the Chukchi Sea. He became one of the few geologists who gained personal familiarity with the entire Brooks Range, and is recognised today as one of the top authorities on North Slope geology.

The discovery of Prudhoe Bay was a team effort. Reminiscing on the experience decades later, Mull, now 80, marvels over being a part of it. But 13 billion barrels of produced oil aside, Mull made important geological contributions of his own, and smiles just as widely when talking about them.

A Pair of Punk Kids

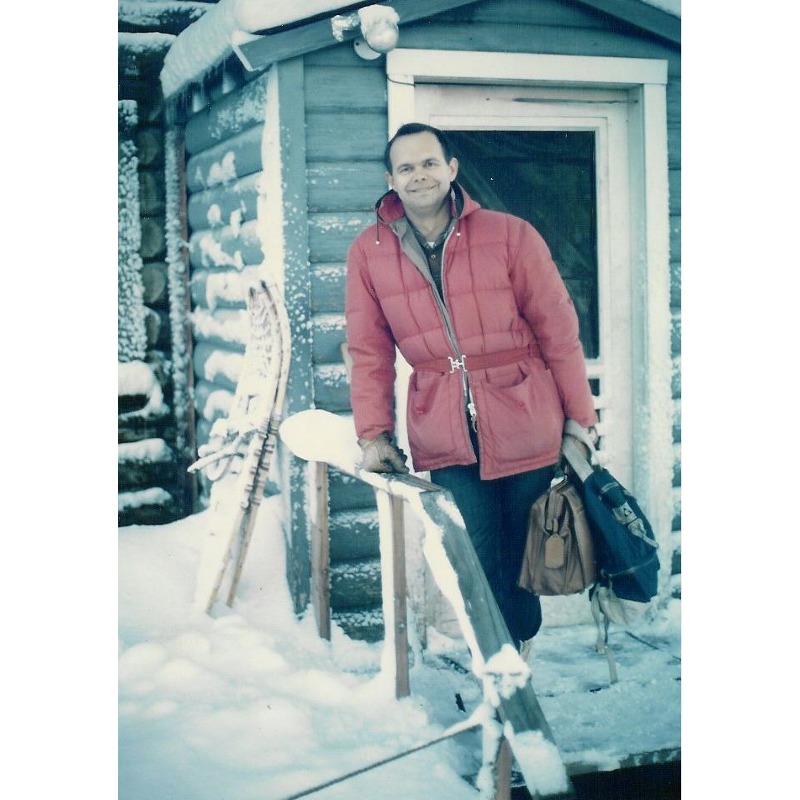

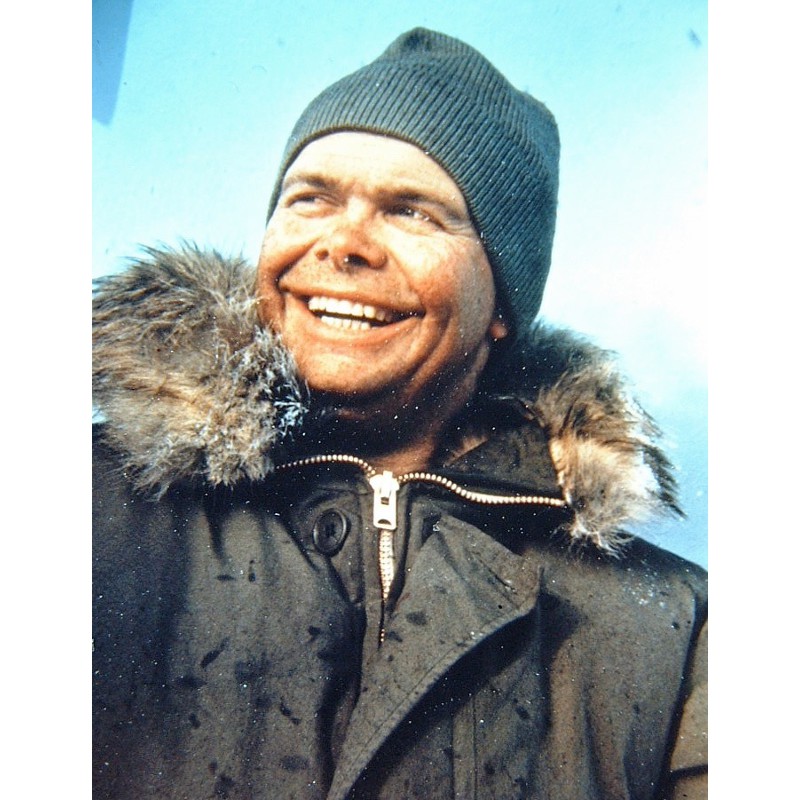

Gil Mull in Otuk Creek, 1965. (Courtesy of Gil Mull)The location was Peters Lake in the north-eastern Brooks Range, and Mull and his field mapping partner, Gar Pessel, found themselves in 1963 camped near a group of geologists from Shell who were older, had PhDs, and “worlds of experience”, Mull recalled.

Gil Mull in Otuk Creek, 1965. (Courtesy of Gil Mull)The location was Peters Lake in the north-eastern Brooks Range, and Mull and his field mapping partner, Gar Pessel, found themselves in 1963 camped near a group of geologists from Shell who were older, had PhDs, and “worlds of experience”, Mull recalled.

Mull and Pessel have often wondered why their supervisors at Richfield Oil, which made the first significant oil discovery in Alaska in 1957 near Cook Inlet, chose relatively inexperienced “punk kids” in their late 20s to represent Richfield on the North Slope.

“We were given a lot of leeway. They gave us a helicopter, a float plane and a budget of $150,000 and told us to go map,” Mull said. “It was a hell of a deal.”

Harry Jamison, who headed regional exploration in Alaska for Richfield, spotted a natural affinity for field mapping in the pair, but especially had his eyes on Mull, who worked at Richfield in the summers while earning his master’s degree. “I wanted Richfield to become more aggressive in their exploration programme on the North Slope,” Jamison recalled. “Gil popped right into my head.”

Needle in a Haystack

Mull and Pessel went to work searching for hydrocarbons north of the Arctic Circle, specifically the areas between the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) and the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska (NPRA) – an area known to contain oil and gas. Relying heavily on the United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) “invaluable” basic framework, they bridged the gaps by identifying potential reservoir rocks and organic-rich shales.

“We covered a lot of country but it was slow,” Mull said. A Cessna 180 on floats or skis transported their camps from lake to lake. A Bell G2 helicopter, which took them into the field daily, could haul little more than its pilot, two geologists and 40 gallons of fuel. A fulltime mechanic was needed to balance its balsawood rotor blades, which soaked up moisture when it rained. “You were elbow to elbow in parkas. It was like being in a straightjacket,” Mull recalled.

Yet they pressed on, spurred by the excitement of exploring the geology of relatively unknown areas and, later, by rocks they observed in the Sadlerochit Formation that showed promise of reservoir potential in the subsurface.

“We really did put our finger on the secret to North Slope geology,” Pessel said. “Toward the end of the summer, we realised that Richfield had to do seismic to look for exploratory targets.”

Believing their recommendations were sound, Jamison convinced Richfield executives to send a seismic crew to shoot general reconnaissance lines on the North Slope in the winter of 1963–4. The following winter, regional lines revealed a structural high near Prudhoe Bay.

“I remember someone asked why we were spending so much time on the North Slope when all the action was in Cook Inlet,” Mull recalled. He kept mum, never mentioning the findings.

Right Place, Right Time

Richfield, which had merged with the Atlantic Refining Company to become ARCO, sent a rig by cat train to Prudhoe Bay in the spring of 1967 to drill the wildcat well Prudhoe Bay State No. 1, in partnership with Humble (now ExxonMobil).

Around this time, Mull joined Humble’s team, not long before the company’s wellsite geologist at Prudhoe Bay resigned to take another job. Mull was ushered in as his replacement. That December, drill cuttings and cores cut from the Sadlerochit Formation revealed porous sandstone and conglomerate.

At that point, daily drilling reports could no longer be sent by radio. Instead, Mull made daily, 1,126 km roundtrips in a Beechcraft King Air to Fairbanks or Barrow to phone them in.

“Well-sitting was something you sent your junior people out to do. It can be awfully boring,” he said. “Well, most of the time.”

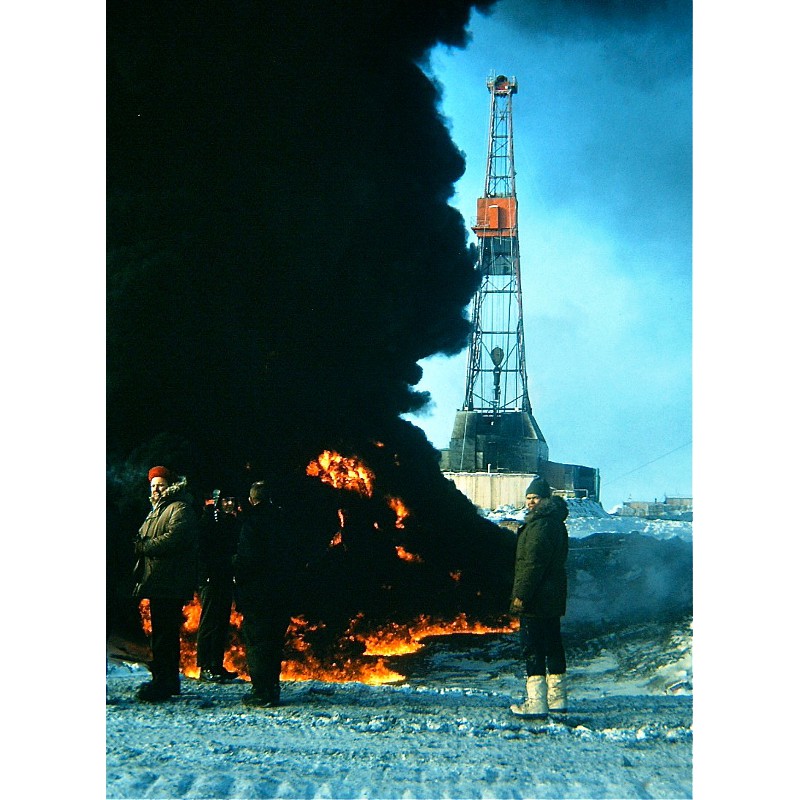

Gil and Bill Congdon, DST #5 site. (Source: Gil Mull).The first drill stem test in the Sadlerochit Formation the day after Christmas brought a present that eventually would give Alaska billions of dollars in tax revenue and the United States an estimated 25% of its oil reserves at the time.

Gil and Bill Congdon, DST #5 site. (Source: Gil Mull).The first drill stem test in the Sadlerochit Formation the day after Christmas brought a present that eventually would give Alaska billions of dollars in tax revenue and the United States an estimated 25% of its oil reserves at the time.

The thickness of the sandstone and conglomerate and the high pressure showed “promise beyond our wildest imagination,” Mull said. “There was an immediate flow of gas to the surface. When ignited, it burned with a roar, a rumble like a jet plane overhead. This test flowed gas for about eight hours and the flare burned all night.”

While the drilling crews conducted a fishing operation, Mull flew to Anchorage to hang out with friends at the Alyeska Ski Resort. There, he was approached by the late Bob Atwood, publisher of the Anchorage Times, who likely heard from airline passengers news of a 15m flare burning in the Arctic darkness. “I hear you have a discovery up there,” Atwood prodded. Mull simply responded, “Oh? I don’t know anything about it.”

In May 1968, the Sag River State No. 1 well, drilled 11 km away and 120m stratigraphically lower, was cored. Roughnecks were screened off from the derrick floor when oil-saturated cores, which consisted of almost unconsolidated sand and gravel, were extracted from the core bit and sent for analysis.

Confirmed: Prudhoe Bay was a world-class, Persian Gulf-sized oil field with an estimated 9.6 Bb of recoverable oil. Dozens of development wells were drilled, topped with Christmas trees, and awaited the completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in 1977.

“Many petroleum geologists can spend their entire careers never seeing a producing well,” Mull said. “This was incredible.”

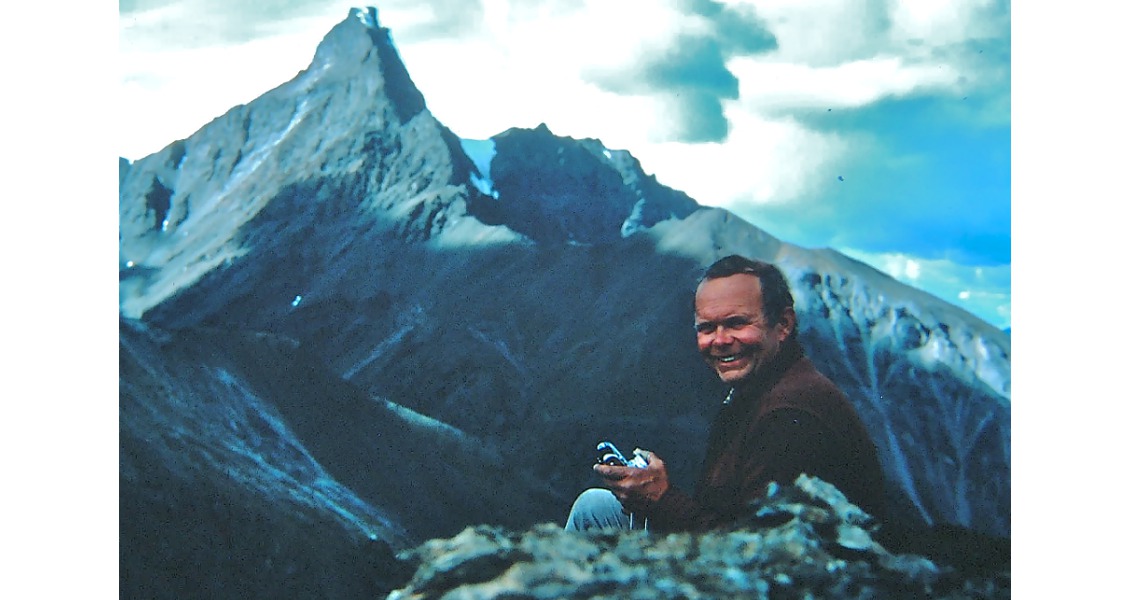

Outdoor Office

As exploration on the North Slope increased exponentially in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Mull essentially was given carte blanche by Humble to lead field parties, mapping the Brooks Range and North Slope from Point Hope to the Canadian border as he saw fit. “To me, the real excitement was going out and wandering around the hills to places no geologist had ever been before and putting together a geologic map. It’s not only a physical challenge but an intellectual challenge,” he said.

During this time, Mull made an important discovery of his own. In 1970, he took Dietrich Roeder, an Exxon research geologist, on a guided tour of the thrust-faulted northern flank of the central Brooks Range. Along the upper Noatak River 112 km south of the mountain front, they noted how the thrust faults had been folded and dipped northward. Roeder suspected that a tremendous amount of movement had occurred in the mountains that lay north of them as a result of an obscure concept at the time: plate tectonics.

A cautious Mull didn’t fully embrace his peer’s assessment until 1972, when he found himself on the flank of Mount Doonerak, 100 km south of the mountain front and many kilometres east of the upper Noatak River. There, he discovered a distinctive rock sequence with fossils that were identical to those in the north-eastern Brooks Range and in the subsurface at Prudhoe Bay. Realising they were very different from the rocks in the mountains north of him, Mull thought, “Wow, Dietrich was correct!”

“The mapping showed that distinctive rock sequences had been telescoped and shuffled like a deck of cards and then folded, representing hundreds of kilometres of crustal shortening. That was mind boggling,” Mull said.

The USGS confirmed the age of the fossils, and agreed that a 650-by-160 km portion of the western and central Brooks Range north of Mount Doonerak had been thrusted hundreds of kilometres northward and then folded by uplift and further shortening in the core of the Brooks Range.

“In terms of geological discoveries, that’s probably the thing I am most proud of,” Mull said.

When Mull caught wind that Humble might send him to Houston for an office job, he quickly jumped ship and joined the USGS’s Branch of Oil and Gas Resources in 1975 to continue his field mapping work, particularly to assess oil and gas potential in NPRA and ANWR, and to help update the USGS’ maps. “We were having fun chasing the mapping. It was like a kid in a candy shop,” said Mull, who also authored an extensive list of technical papers and maps on North Slope geology.

He continued that work when he moved to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys in 1981 and then to the Department’s Division of Oil and Gas in 2001. During this time, Mull led field parties that included graduate students from the University of Alaska Fairbanks that he described as “heroes”, as they provided a lot of the geological documentation critical to many projects.

The Go-To Guy

Mull, who is married with two children and three grandchildren, retired in 2003 and has settled in Santa Fe, N.M. He continues to take calls from fellow geologists to discuss the rocks he knows so well on the North Slope.

“I think Gil was one of the best field geologists I have known in my long career, and in this business I’ve known some good ones,” Jamison said. “His expertise on the North Slope is basically unrivalled. From that standpoint, he occupies a unique niche in the geological fraternity. Gil was one of the foremost historians in the discovery of Prudhoe Bay.”

As important as the discovery was to his country, a modest Mull holds the years he spent in the Brooks Range as the most meaningful. They fuelled his mind and soul and gave him a career that had few boundaries, two being the rugged terrain beneath his feet and the canopy of sky above his head.

With that freedom, he pushed science a step forward.

Mull often borrows the words of Alaskan geophysicist John Eichelberger: “Although it’s risky, exploration is still the heart of science.” Then, he adds a few of his own: “And, science is the heart of exploration.”