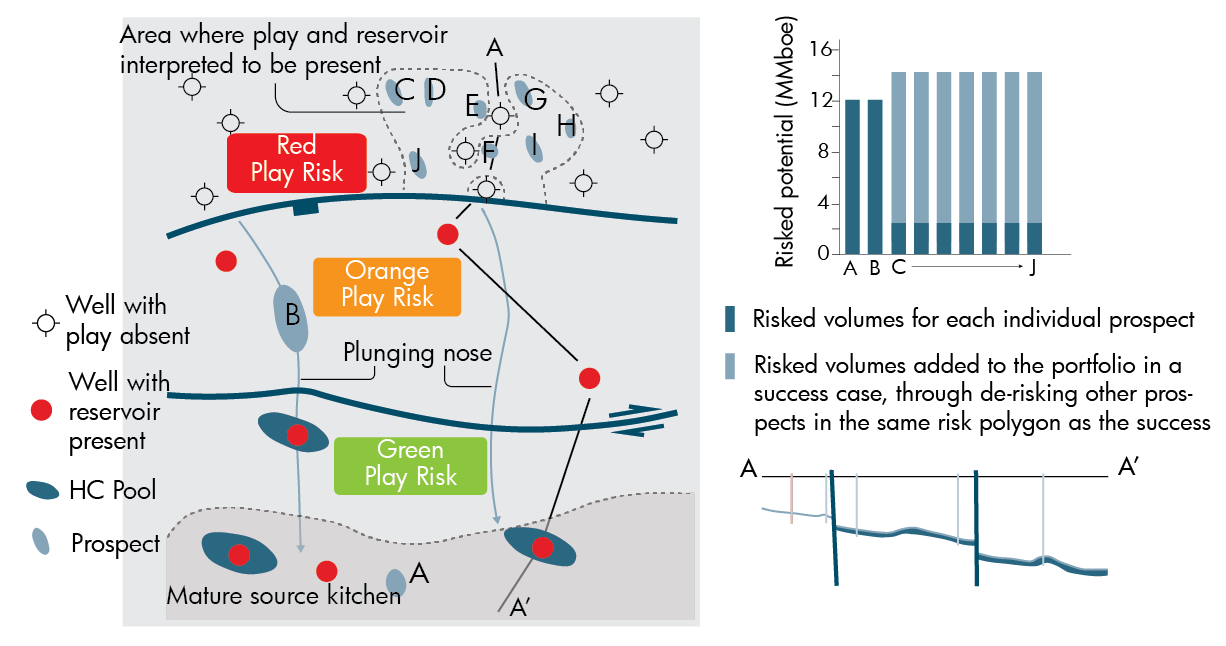

When exploring a new area, it is common for E&P companies to produce traffic light maps, with red areas being the ones where one of the key play elements is missing, orange where one is uncertain, and green where all elements are thought to be present.

However, the fundamental flaw of working with this methodology is that a traffic light map only considers risk. No exploration decisions are made on risk alone, it is always the combination of risk and reward (volumes). Only focusing on risk can lead to situations where the best prospects are, in fact, ignored.

What should be done instead, is to link risk and a reward in all polygons in a play map and perform a ranking in that way. It is called split risk play mapping, and it is the only play-based exploration methodology that fully integrates both risk and reward and has been around for a long time. That doesn’t mean it is a widely-recognised methodology, though.

The outcome of using the split risking approach (where each polygon includes a shared play risk and a non-shared ‘prospect’ risk) can be widely different from using a traffic light approach. The main reason is that if one well demonstrates a play element to work in what would be a red area, it can impact multiple other prospects in that same red polygon. Notably, this only applies if the risk for one prospect also applies to the others in the same red polygon.

The example shows a map of three zones, which could have been interpreted as green, orange and red from south to north. However, look at the risked volumes, and what happens when a well proves prospect C to work? This then subsequently de-risks seven other prospects within the same polygon, which means that the combined risked upside of this cluster of small prospects amounts to 115 MMboe. That is a lot more than the risked potential of prospect B (12 MMboe and the only prospect where a success would deliver a commercial volume), which is the one that most people would have chosen if relying on a traffic light approach.

This clearly shows the value of properly risking prospects, even in what would be a red area when using a traffic light approach. If anything, this example shows that using a traffic light approach is dangerous and unjustified.

This is the third of a series of articles based on work and experience from the GIS-Pax team in Australia, as presented by Ian Longley in a series of videos on LinkedIn.

Find the previous articles here:

Why the term “fault block” is a useless way to describe a trap