Imagine an onshore petroleum province that has three proven plays and a supergiant oil field suddenly opening up for international business and exploration companies. Except, it has no modern seismic data, no recent wells, and almost zero data available from historic oil fields. This was Iraqi Kurdistan in 2006 – 2010. Imagine the stampede of junior petroleum exploration companies, followed soon after by National Oil Companies and petroleum supermajors. It was exhilarating.

Imagine an onshore petroleum province that has three proven plays and a supergiant oil field suddenly opening up for international business and exploration companies. Except, it has no modern seismic data, no recent wells, and almost zero data available from historic oil fields. This was Iraqi Kurdistan in 2006 – 2010. Imagine the stampede of junior petroleum exploration companies, followed soon after by National Oil Companies and petroleum supermajors. It was exhilarating.

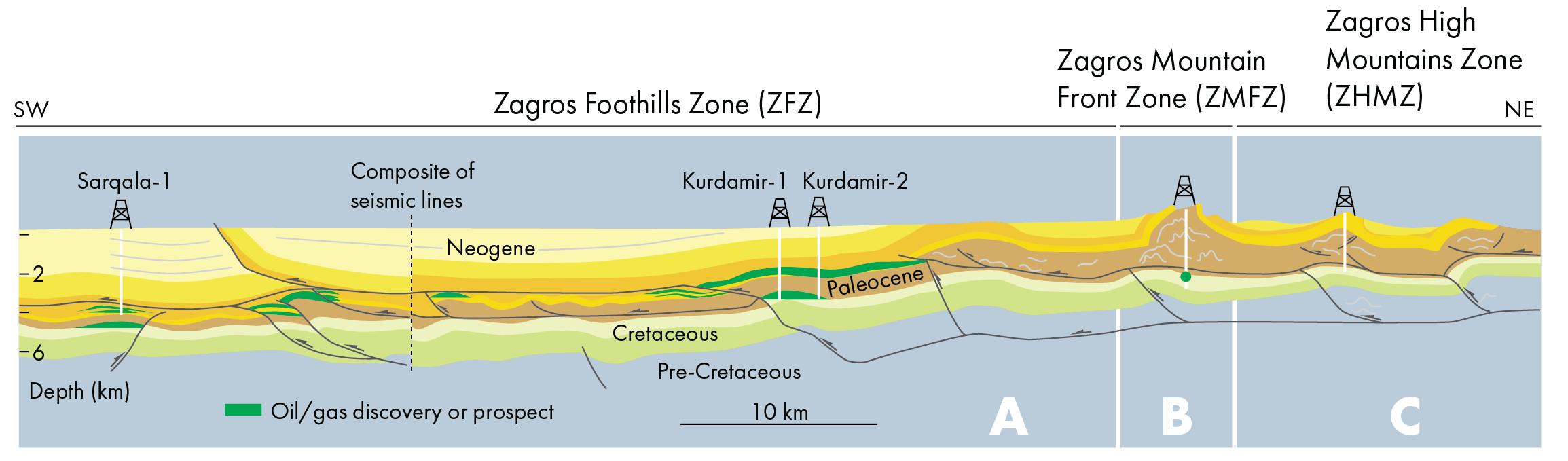

Imagine yourself as an Exploration Director. Where in 30,000 km2 would you lease exploration license blocks using only anecdotes in textbooks, surface geology maps being hastily created from pre-Google Earth satellite imagery, and a few PDFs of wireline SP logs from 1970s wells? A, B or C?

A. The Zagros Foothills Zone (ZFZ): Flat topography; long, linear surface synclines between emergent thrusts; >2 km thick molasse overburden; the region’s dominant petroleum topseal eroded off the occasional hills; rumours of reservoir overpressure.

B. Zagros Mountain Front Zone (ZMFZ): The first belt of textbook, whaleback anticlines–each 40 km2 and 0.5 km tall–capped by the region’s dominant petroleum reservoir.

C. Zagros High Mountains Zone (ZHMZ): Several belts of whaleback anticlines – each up to >50 km2 and >1 km tall – that expose new plays containing high porosity-permeability.

Most companies flocked to the ZMFZ (B) and ZHMZ (C) to, “drill the biggest anticlines” and, “prove new, deep plays.” With only limited success. There are several likely explanations that are evident from scrutiny of the surface geology and analogue orogenic belts: Petroleum system components are exposed to meteoric processes; 3 km of overburden erosion indicates reservoirs had been deeply buried; some porosity-permeability was caused by weathering; seismic acquisition in sheer topography often yields uninterpretable imagery that causes drilling prognoses to be very uncertain.

Instead, WesternZagros Resources and I selected ZFZ (A). Why? Experience exploring other orogenic belts provided confidence that: The thick molasse overburden and near-surface synclines would enable good seismic imaging of the underlying anticlines; high probability of retention of tall petroleum columns; similarities between the anatomy and uplift mechanisms of the Zagros and Canadian Rocky Mountains orogenic zones; a strategy to pursue the most probable reservoir traps rather than the biggest surface anticlines.

As proof of our hypotheses, WesternZagros Resources discovered the Kurdamir oil-gas field and Sarqala oilfield in the ZFZ in fault propagation folds on excellent seismic imagery. Fifteen years on, the ZFZ has yielded almost all of the petroleum fields and produced barrels of oil and gas.

To conclude, when exploration geoscientists build new plays and prospect portfolios, they must: Step back and model the entire tectonic region, apply learnings from analogue geologies, collaborate closely with well-design engineers to prognose structural deformation, and replace gut feelings with multiple, testable hypotheses.