Nature does not respect the licence boundaries drawn on a map by humans. Oil and gas accumulations straddling licence boundaries are common. The size and shape of blocks, in combination with the nature of the geology and hydrocarbon accumulations, impacts the prevalence of straddling fields. Further licensing activity, field delineations, unitisation agreements, relinquishments and relicensing will further fragment this picture, often creating ideal conditions for straddling situations.

I Drink Your Milkshake

In the 2007 Hollywood feature film, ‘There Will Be Blood’, Daniel Day-Lewis plays the part of an oil prospector in the California oil boom of the early 20th century. Some readers may recall the well-known scene where oil production from different licences is likened to drinking the same milkshake from two different straws; the entire milkshake can be drained from just one straw. This is known as the ‘rule of capture’.

Finders Keepers

The ‘rule of capture’ is the situation where hydrocarbons become the property of whoever recovers them, even if they have migrated from the subsurface in adjoining lands. Rule of capture was prevalent in the early days of the oil industry, especially in the United States.

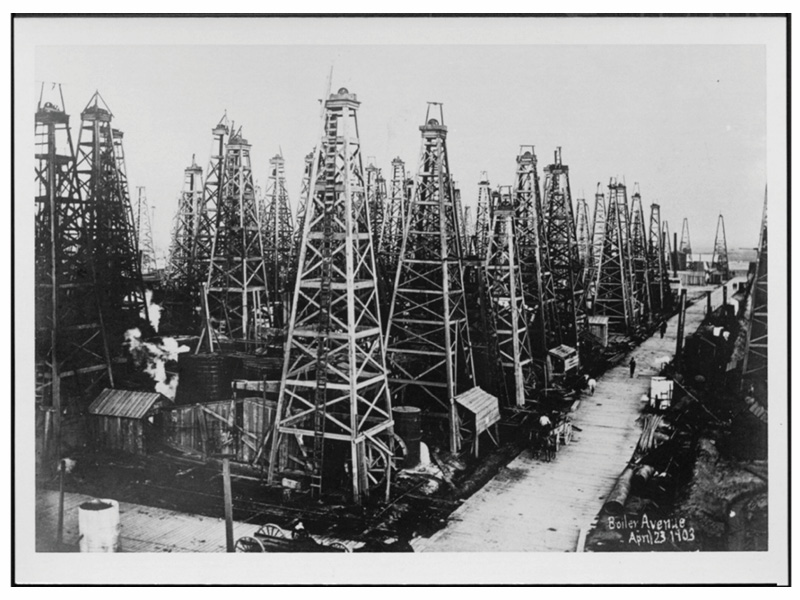

The rule of capture encouraged landowners to drill and produce oil and gas quickly and before their neighbour did. This led to inefficient recovery, duplication of effort, too many wells and reservoir problems including coning, fingering and premature loss of reservoir energy. Figure 1 shows the result of rule of capture in Spindletop’s Boiler Avenue in the East Texas oil field of 1903 and illustrates what happened when the rule of capture was prevalent.

Many stakeholders and people involved in the oil industry at the time, such as Harry Doherty, founder of Cities Services, called for an end to these “extremely crude and ridiculous” production practices. In the US, regulatory provision was introduced at the state level through bodies such as the Texas Railroad Commission. These measures included compulsory pooling of leases, well spacing rules (e.g., 40-acre spacing) and restrictions from drilling closer than a certain distance from a lease boundary.

Although rule of capture is now less prevalent in the oil and gas industry, there are several situations where it still occurs. These may include international situations with no agreement in place, in countries with no regulatory unitisation provisions, or where regulatory provision is in place but not implemented. There can also be situations where parties are aware it may be occurring but prefer to keep quiet and avoid the cost and hassle of formal unitisation.

Why Do We Do It?

Unitisation, and other measures, such as minimum well spacing and pooling, are designed to avoid rule of capture, and ensure that the petroleum resources of the state or country are developed in an optimum and efficient manner, which includes:

- Maximising the economic recovery of petroleum from the accumulation, for all parties.

- Ensuring a fair allocation of resource revenues and costs.

- Sharing and making best use of technical information.

- Reducing development costs and improving project efficiency.

Providing an equitable split between parties is not the main driver behind unitisation, although it may also be a desirable outcome.

What is Unitisation?

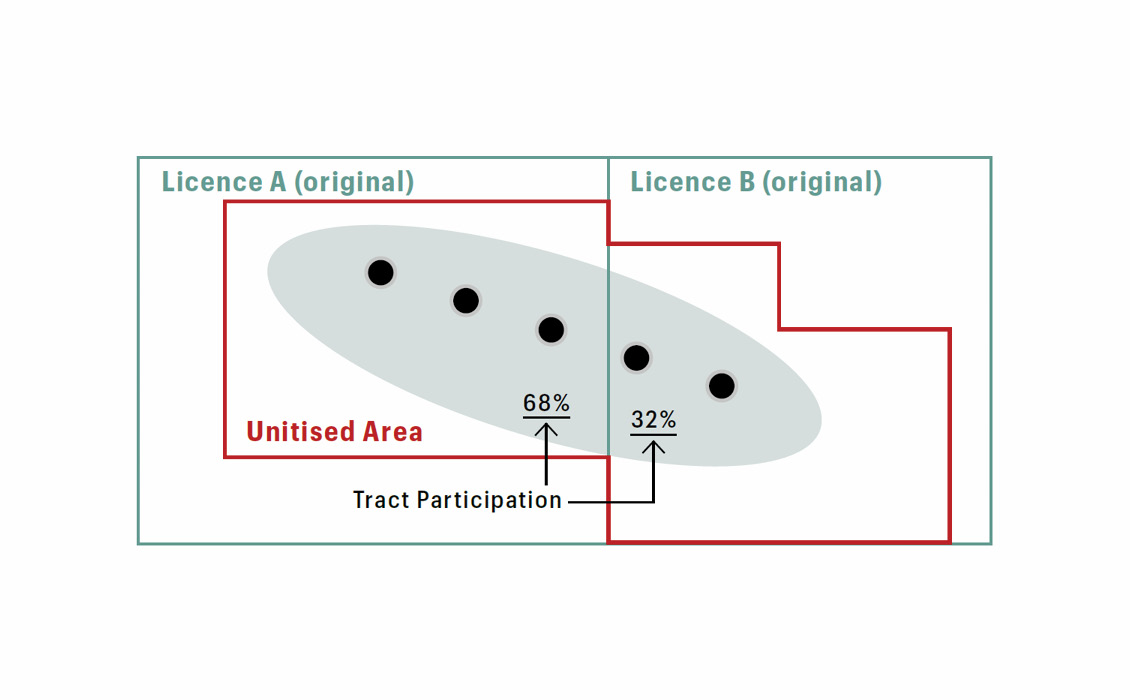

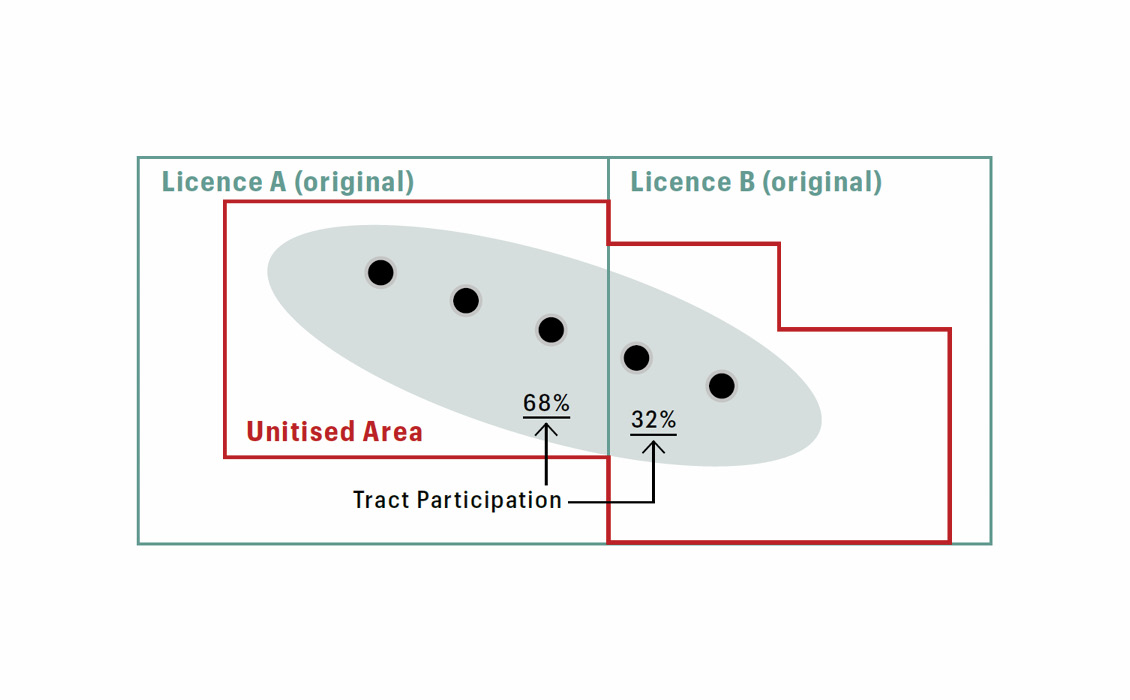

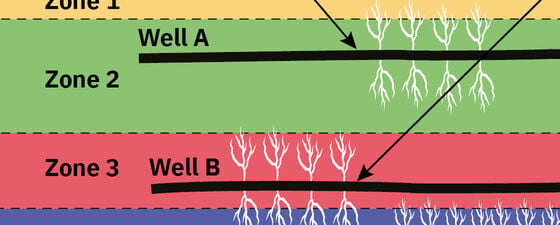

Unitisation is the process by which development of a field that crosses one or more licence (or international) boundary(ies) can take place as a single ‘unit’ (see Figure 2 for a cartoon example). Licensees of neighbouring leases pool their individual interests in return for an interest in the overall unit. Development proceeds as if the original licence boundary does not exist. The share of production, and cost, allocated to each side of the original licence boundary is known as the tract participation.

In many jurisdictions a state energy regulator will require that straddling fields be unitised as a pre-condition for field development approval.

Although domestic unitisation is a contract between private parties, with limited state involvement, a strong and proactive regulator can step in and impose agreement on parties who would otherwise be unable to agree. For the Zama field in Mexico, it was reported that if parties could not arrive at an agreement within a specific timeframe, the energy ministry would propose the terms of a unitisation and unit operating agreement (UUOA).

Unitisation is often problematic with multiple technical and commercial challenges, and in practice there is no perfect solution for all the problems and difficulties associated with unitisation.

Modern Best Unitisation Practice

Although many measures were introduced in the US and other countries from the 1930s, modern international best practice for unitisation developed primarily in the North Sea during the 1970s and 1980s and included both domestic and international straddling fields. Early international agreements included the Frigg Agreement for the large gas field straddling the UK/Norway boundary. During the 1980s and 1990s, many unitisations took place here such as Statfjord, Nelson, Balmoral and Armada.

The unitisation process is usually governed and defined by a UUOA, or equivalent, which sets out how the unit is managed. A UUOA replaces a Joint Operating Agreement (JOA) in a unitised field, but includes the unitisation provisions.

Ideally, a UUOA should be executed prior to development and prior to approval of a field development plan. Although unitisation can, and does, sometimes occur post development, it is not an ideal situation as the main benefits of an efficient development would already have been compromised. A UUOA may have evolved from a pre-unit agreement (PUA) used during the appraisal stage. PUAs are useful as they establish many of the key issues which will be required in the UUOA and allow activities to proceed efficiently, which might include data-sharing, appraisal activities, preparation of development plans etc. An outline for a UUOA is provided by the Association of International Petroleum Negotiators (AIPN), whichalso includes consideration of exploration activities in its most recent update in 2020. Figure 3 shows which agreements are typically applicable for the lifecycle stage of a straddling field.

Redetermination and Technical Procedures

Redetermination is the process whereby the tract participations are revised at some time after the initial unitisation and is typically triggered by defined events such as additional data being acquired, e.g., a major drilling programme or new seismic acquisition, a specific time after production start-up or a specified amount or percentage of estimated ultimate recovery. A field may have one or more redeterminations throughout its life. Although the concept of redeterminations is simple, the process can be expensive, time-consuming, and contentious.

The preparation of a submission to an expert often takes an integrated team of dedicated staff many months or in some cases years. This can be a considerable cost. Add in the opportunity cost of taking staff away from their regular jobs, the cost of the external expert, and the risk of litigation, and the investment can be considerable, not to mention the intangible costs of potentially damaged relationships within a joint venture. Such costs can then be weighed against the potential value of a change of tract participation.

However, in a large field even a 1% change of equity interest might be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. It is worth noting that the redetermination process does not produce any more oil or gas; it is simply re-adjusting the share. Perhaps the most common, and well-known use of an external expert is for the redetermination of tract participation, whereby the basis for tract participation, usually hydrocarbons in place, and the technical procedures have already been agreed and are specified in the unitisation agreement.

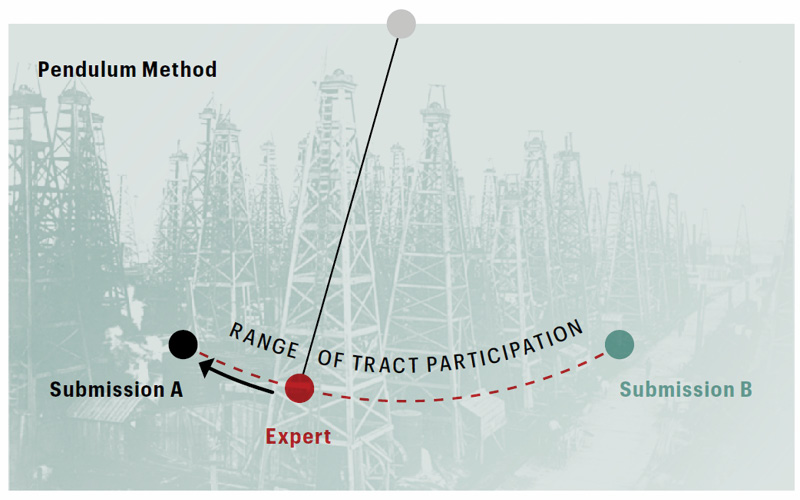

The Expert and the Pendulum

The expert must deliver their decision according to the protocol of the unitisation agreement. There are various ways in which this can be done. These may include an expert delivering their own decision, which may be different from submissions by individual parties, or sometimes within a prescribed range. A common method, promoted by the AIPN, is the pendulum method, which is intended to discourage extremism in submissions. In the pendulum method, the expert must choose the submission closest to its own determination. In Figure 4, Submission A would be selected. The pendulum method works best when there are only two parties, as with additional submissions there is opportunity for manipulation of outcomes.

The Winner Takes It All?

Unitisation, and in particular, redetermination is often considered as a zero-sum game, with clear winners and losers. Most UUOAs contain payback clauses such that an increase in equity also requires a back-adjusted payback of costs.

During the first redetermination of the Balmoral field in the UK North Sea, the ‘winning’ party, that increased their equity share, commenced legal proceedings as they preferred to lose. At the time of the redetermination, low commodity prices coupled with high development costs meant that an increase in equity resulted in a considerable loss of revenue.

Furthermore, payback of costs is often made within a specified, limited time, which is usually much shorter than the remaining life of the field. Thus, there may be times, such as during a period of low product prices, when losing, and receiving cash, and a reduction of potentially limited revenues over a longer timeframe, was preferable to winning and having to pay back cash now.

Is It Avoidable and Are There Alternatives?

In mature provinces such as the North Sea, the heyday of unitisation is long gone. As new fields become smaller, the size of the prize often no longer justifies the time, and cost of a unitisation. Alternatives to formal unitisation are often considered and implemented. One solution is fixed equity; one of the first fixed equity agreements, in 1994, was for the Armada gas complex in the Central North Sea, a situation with multiple fields, multiple owners, and a complex ownership structure. Another solution is asset swaps whereby parties exchange assets to simplify ownership structure. More recently, the Peik field, which straddles the UK/Norway, has an agreement that states the Tract Participation will not be adjusted or amended unless unanimously agreed by the parties, removing the need for redetermination, and providing an agreed fixed equity.

Other solutions include buyouts or cash payments; in fact, anything that can be agreed between the parties.

International Issues

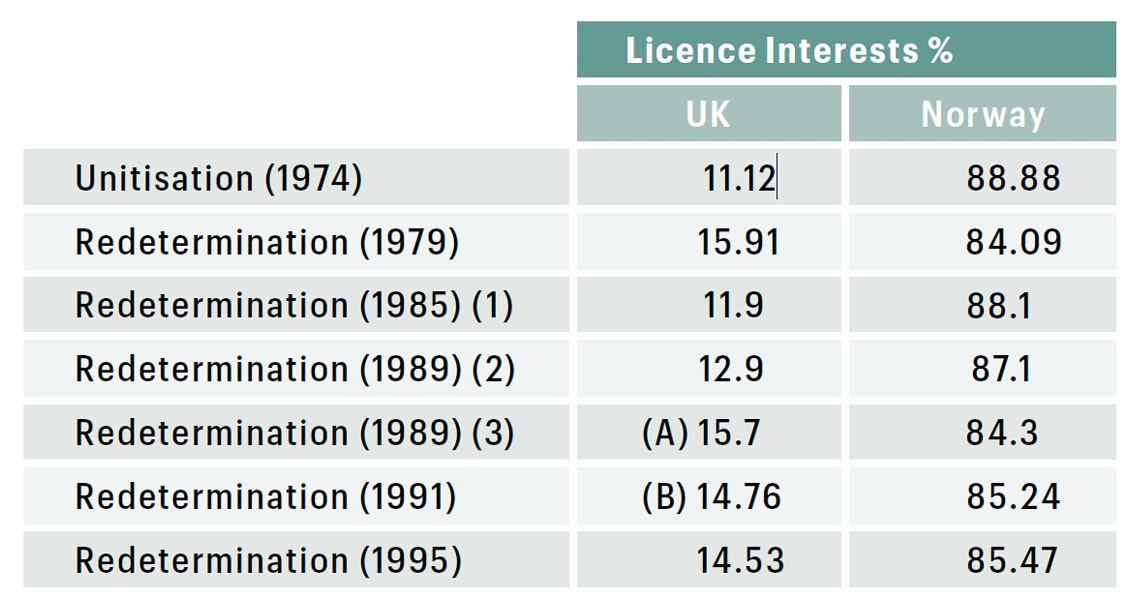

Fields straddling international boundaries introduce a whole new level of complexity and require cooperation between governments. If the border itself is not agreed, then a first step is typically a delimitation agreement. In the North Sea, a series of delimitation agreements preceded unitisation of individual fields. If the border cannot be agreed, then various options are available. Even if a boundary is not formally agreed between the countries, a boundary can be agreed solely for the purposes of unitisation to allow development to proceed. Another common solution is to create a joint development area to allow exploitation of resources. There are many examples of these including: Malaysia–Thailand, Australia–Indonesia, and Nigeria–São Tomé and Príncipe. Without any agreement, prospective acreage can remain unexplored and undeveloped such as that in the Cambodia–Thailand overlapping claims area. An example of multiple redeterminations, from the Statfjord field, offshore Norway, is shown in table 1.

Back to the Future?

There are many high-profile international unitisations at various stages of maturity around the world. Some examples include: the Zama field in Mexico, several fields in the eastern Mediterranean, Jubilee and Afina-Sankofa in Ghana, Areas 1 and Area 4 in Mozambique and sub-salt fields in Brazil.

There have also been several high-profile government agreements in recent years. In 2010, after years of negotiation, Norway and Russia signed a maritime delimitation treaty and in 2018 Brunei and Malaysia announced a unitisation framework agreement for several fields straddling their border.

An interesting example is the Greater Tortue/Ahmeyim gas field which straddles the border between Mauritania and Senegal. An agreement was reached in 2018 which provides for development of the field with an initial 50/50 split of resources and revenues and a mechanism for future redeterminations. The agreement was reported as being based on industry best practice for development of cross-border resources and was therefore based on the landmark 1976 Frigg Agreement between the UK and Norway.

The Future of Unitisation

Many oil and gas fields straddle boundaries. The main purpose of unitisation will remain to ensure efficient development of these resources. Regulatory provision for unitisation may need to be strengthened and properly enforced. This may require regulators to take a more active role. Unitisation is often, and should remain, a pre-requisite for development approval.

Unitisation protocols and common practices have been established worldwide, largely based on North Sea practice. These provide the industry with a basis for unitisation; however, other methods and processes may be more applicable in other areas. Unitisations are often contentious and can have unintended consequences, such as damaging relationships within a joint venture. Alternatives to unitisation, such as fixed equity, assets swaps and buyouts are options that can be considered and may be preferable to a formal unitisation. It may be better to make the pie bigger for everyone rather than fight over the size of each slice.

However, for large accumulations with high potential values, unitisation will remain the most-likely process.