In the far south of Iran, next to the Hormuz Strait, is a little-known island that epitomises the rich Persian culture, with archaeological remains from ancient civilisations and outstanding natural features that form an excellent basis for eco- and geotourism. An astonishing eroded landscape of Miocene to Holocene sediments awaits the visitor, while the cultural history is exotic and enticing.

Qeshm (pronounced Kesh’m, sometimes with silent ‘m’) is the biggest island in the Persian Gulf, five times the size of Singapore. Surrounded by blue subtropical seas, the island is an attractive mix of wind- and ‘flood’-eroded mountains, springs, sea forests, reefs and wildlife. Low flat-topped hills no more than 200m high contrast with plains, which run up narrow tongues into the hills. Adventure might be wandering with camel herds, chasing a desert fox away from a laying turtle or your first taste of whale shark oil or local fish. And, if bird-spotting is your delight, try Qeshm in late winter.

Environmental Awareness

Qeshm now has a population of approximately 100,000 people and attracts some 700,000 visitors, most coming from the mainland. Such growth might be a recipe for ecological disaster in this sensitive environment, and to counteract that a sustainable development plan has been put in place through the Qeshm Free Area (QFA) authority, which was established in 1990 as one of the three free trade and industrial zones in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

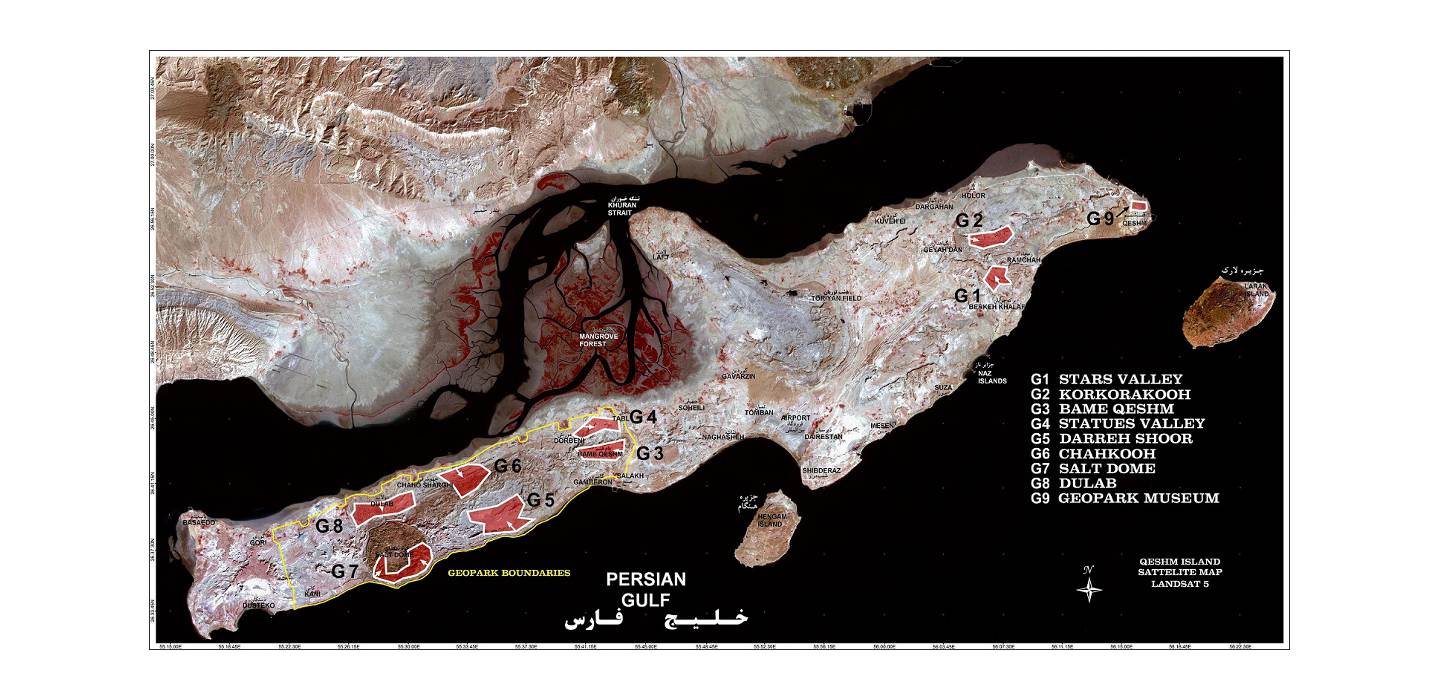

Bijan Darehshoori, naturalist, author of ‘Nature of Iran’ (2009), and QFA environmental manager for over a decade, spent over a decade moulding Qeshm into an environmentally sustainable island, creating work for future generations. His vision brought sustainable use and recycling, a turtle hatchery, a ban on whaleshark fishing, and protected and extended mangroves giving habitat for birds and fish alike. In 2006 Qeshm became the site of the first Iranian National Geopark and was until 2012 also in the UNESCO-assisted Global Geoparks Network.

Salt and Desert

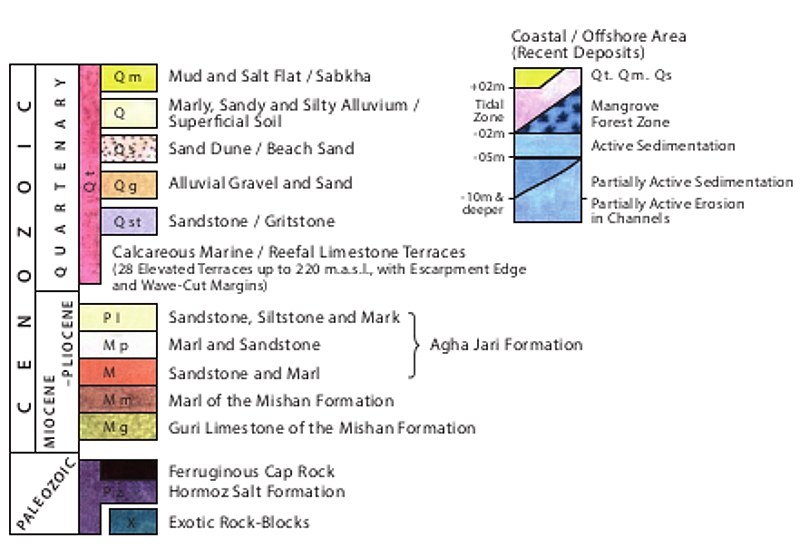

The geological structure of Qeshm is oriented west-south-west to east-north-east, parallel to the coastline and the main regional trend of the main fold axes. The western end of the island has little vegetation, exposing a continuous mid-Tertiary to Holocene fossiliferous succession and containing a major salt dome with a Precambrian-Palaeozoic record. The Kish Kuh (the island’s highest point) area is given as about 400m above sea level but because of the salt mobility is rising a few centimetres a year.

The Gulf coast, with its heavy humidity, is crossed by warm, damp eroding winds, the Shamal, out of the Arabian Desert. Conversely, rainfall is sparse, 155 mm on average annually, and in a drought it can be as as little as 10-20 mm, so desertification has set in. The climatic regime has created a unique geological and natural status over the past millennia that have produced fantastic eroded structures.

The first geological mapping was done early in the last century mainly by Englishmen working for Anglo-Persian or the British Government, mostly in search of oil and gas.

The stratigraphy of Qeshm.What they found, however, was salt, and they smelt lots of sulphur and saw lumps of asphalt washed up on the shore. All the rocks were placed in the Miocene to Pliocene Fars series, with the massive salt dome ‘Kuh-E-Namkdan’ then thought to be Jurassic or Triassic at most, although it is now known to be much older.

The stratigraphy of Qeshm.What they found, however, was salt, and they smelt lots of sulphur and saw lumps of asphalt washed up on the shore. All the rocks were placed in the Miocene to Pliocene Fars series, with the massive salt dome ‘Kuh-E-Namkdan’ then thought to be Jurassic or Triassic at most, although it is now known to be much older.

Qeshm’s salt, long known to island visitors and invaders as the purest in the Persian Gulf, was exported in the 19th century as blocks destined for Calcutta and east Africa; now Qeshm’s hidden gas may take the same routes. The Geopark management decided to restrict salt mining to methods not using explosives and to keep it away from geoheritage features such as the salt caves, proven to be some of the longest in the world.

Water is the key to Qeshm’s history, no less now than in the past, as it is vital for both tourism and industry. The traditional system of land ownership is based on watersheds and using the geology to trap fresh water. Ancient Persian dams have been upgraded into modern times. But with more rapid use many of 350 wells now yield salty water suitable only for irrigation of mangrove and date palms. The island uses desalination plants as well as grey water recycling.

Qeshm’s Geopark

G1: Stars Valley

G1: Stars Valley G2: Korkora Kooh

G2: Korkora Kooh G3: Baam-e-Qeshm

G3: Baam-e-Qeshm G4: Valley of Statues

G4: Valley of Statues G5: Darreh Shoor

G5: Darreh Shoor G6: Chahkooh

G6: Chahkooh G7: Salt Dome & Caves

G7: Salt Dome & Caves G8: Dulab

G8: Dulab Mangrove Forest

Mangrove Forest Citizen Science on Qeshm

Citizen Science on QeshmWhat of Qeshm’s Future?

In 1990 the Iranian government designated Jazireh-ye Qeshm as a Free Area (QFA) – a special economic zone that offers a secure, stable environment with tax concessions, tax holidays, unimpeded circulation, convertibility, and freedom and repatriation of foreign currency and capital. The government is prohibited by law from confiscating property and there is an independent forum to adjudicate disputes. Specific incentives for foreign business include visa-free entry, 100% ownership possibility, exemption from customs and duty and streamlined issuance of work permits. Modern infrastructure and facilities have brought American, Asian and European companies to work alongside Iranian counterparts, investors and industrialists. Meanwhile, construction of a 2.2 km bridge over the Khurân Strait, linking Qeshm Island to the port of Bohal, commenced in 2011.

The Persian Gulf region is synonymous with the extraction of oil and now gas. Qeshm is a major player in Iran’s upstream activities and has yielded two enormous anticlinal gas fields. The gas giant field on Qeshm, Gavarzin, has already been developed and gas piped to the mainland. There are offshore oil reserves between Hormoz and Larak and between Larak and Hengam – all these islands and related structures, as in Qeshm Geopark, are salt domes, a key to petroleum resources. Onshore, the central north-south anticline has been developed and gas is piped to the mainland for the power plant at Bandar Abbas.

Salakh, a giant gas field in the central west, was discovered in 1961. Its recoverable reserves have been estimated at over 12 Tcf. Because of high acidic gas and nitrogen content it did not become operational on discovery. In 2005, the QFA made the decision to protect the field against development, making it a major part of the Geopark, providing scientists with an open-air lab on the effects of such a structure.

However, in 2007 interest in boosting oil and gas production on Qeshm was revived. Gas condensate and crude oil refineries, with capacities of 120,000 bpd and 160,000 bpd respectively, are being built. A crude oil conveyance pipeline will go from Qeshm to the Bandar Abbas refinery and gas from Siri island is now connected to west of Qeshm by pipeline. A joint project by the private sector and the Oil Industry Investment Company (OIIC), the pipeline was mooted to come on stream in early 2008, although there is not clear evidence that it did. And in 2011 Iran started building its first refinery capable of processing ‘heavy’ oil in the southern part of the island. Crude will come from Iran’s Soroush and Norooz fields, and the refinery will be capable of producing as much as 30,000 barrels of light oil a day.

Authorities also report that the QFA and NIOC are discussing with several foreign firms for the development of Salakh gas field. The aim is to supply markets in India and East Africa. An estimated US$ 500 million would be needed for the development and so the QFA government will not start extracting soon but as with the bridge across the strait, there are now concerns that gas industry infrastructure might detract from the island’s ecotourism credentials.

So what of Qeshm’s future? Sustainability by keeping Salakh for research within the Geopark seems to have been overturned for more immediate resource development benefits. Are the two incompatible? Will Qeshm retain its status as the Geoheritage Pearl in the Persian Gulf?

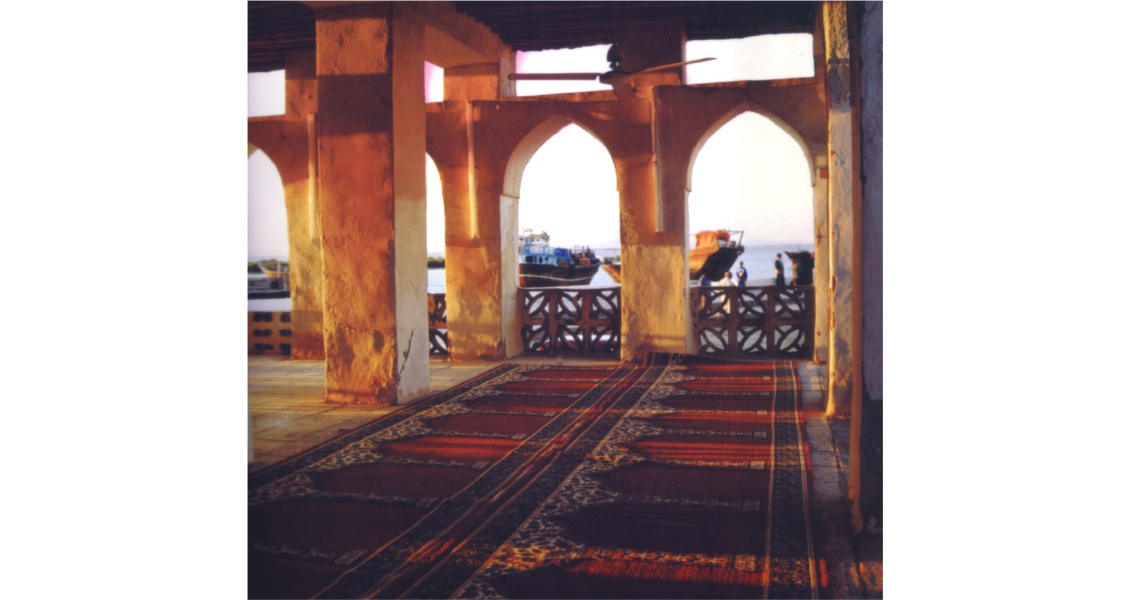

What really makes this island special is not just the geology; it is the Qeshmi people, a mix of ancient Persian, Gulf and ocean-going wanderers such as the Portuguese and British who passed through as empires waxed and waned. With their distinctive culture, dress and more relaxed lifestyle than the mainland, the locals have survived this salt-infused environment by adapting with the ups and downs of the coastline – even harvesting rainwater by using the geology.