To assist geologists in orientating cores correctly in terms of what is up and what is down, the outside of the core is often marked with a red and yellow line, the so-called tram line. Red is right, yellow is left.

In many cases, this is a great help, especially if you are not an expert in sedimentology. At the end of the day, only a small selection of cores show clear sedimentological indications allowing the interpretation of the correct orientation of the core. Think of bottom-set laminations or the way cross-bedded sandstones are truncated.

There is one sedimentary succession in the North Sea where inspection of the tramlines is very often unnecessary in order to find out what the orientation of the core should be. That is the Ness Formation from the Northern North Sea.

The sediments of the Ness Formation were deposited during the Middle Jurassic and form part of the Brent delta succession that is characterised by a series of delta progradations and retrogradations.

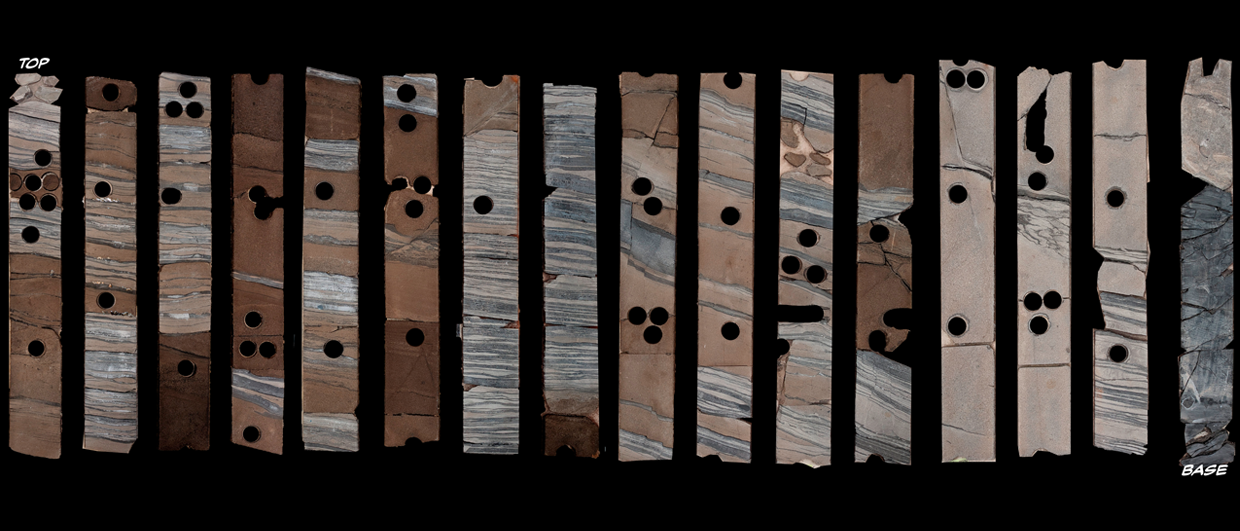

Ness Formation strata are characterised by beautifully laminated fine-grained sediments, as the image illustrates. It is the alternation between darker mudstones and whitish fine sands, in which very often wave ripples can be interpreted, that make Ness Formation cores so distinguishable.

Top of the delta

Ness Formation sediments reflect a low-energy environment, where mud was deposited most of the time. However, a sediment source for coarser-grained siliciclastics must always have been close-by, given the frequent intercalations of sands. Most people attribute the Ness sediments to a delta-top environment, where shallow lakes accommodated settling of fines, with intermittent input of coarser material from nearby distributary channels.

If the laminated fine sands cannot already be the clue towards putting a Ness core in the right orientation, then there are trace fossils that can do the job. What is generally thought of being the work of Diplocraterion, these bottom-feeders dug their way into the soft sediments of the Brent delta plain.

Due to subsequent sediment compaction, the original mostly vertical burrows now often show up as a squiggly line, but that does not take away the possibility to discern the starting point from where the burrowing started.

Very often, it is a slightly sandier bit that formed the starting point of a new burrow, clearly enabling geologists to conclude what is up and what is down when looking at a bit of Ness. Even when the tramlines are missing.