Visiting Northern Jutland’s famous fossil beds

When God had finished creating the Earth, He had some sand and gravel in excess. To get rid of it, He dumped it in the southern North Sea, and that became Denmark.

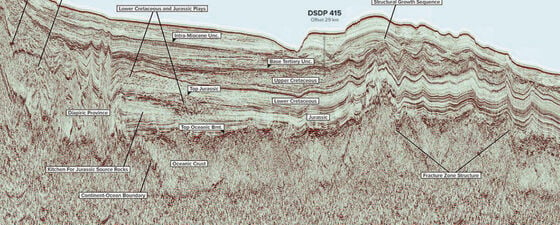

Or so the story goes. For geologists, this sediment heap reflects a varied range of deposition environments ranging in age from the Lower Cretaceous through to the Pliocene. Denmark is slightly tilted to the south-west, with the oldest rocks exposed on North Jutland, and becomes progressively younger south-westwards.

Seismic data and drilling for ground water, petroleum and salt have proven even older rocks below: Salt is produced from Zechstein diapirs, and in 2015, Total drilled for shale gas in Cambrian hot shales at four kilometres depth. They found gas, but the shale was too thin to be commercial.

The Tropical Sea

Here, we will look into and onto the younger rocks on the surface. Most of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments in Denmark are marine, and fossils are abundant.

One interval is especially rich: the Lower Eocene diatomitic sedimentary rock known in Denmark as ‘Moler’; the goal of our visit. It comprises about 60% silica-based skeletons of diatomic microfossils, with 30% clay and 10% volcanic ash. Deposition of this horizon began at the Palaeocene-Eocene boundary, 55.8 million years ago, and continued for around three million years, as Denmark moved from a tropical climate with deposition in an isolated sea to a more temperate environment, with contact to the open ocean, the proto-North Sea.

How to get there

North Jutland. (Source: C. Hansen)

The closest major airport is Aalborg, with flights directly from Copenhagen, Amsterdam, London, Berlin and Oslo.

Driving distance to Fur is ca. 80 km. A bus services exists, but renting a car is the most efficient way to get there – or do as I did: go by bike. Denmark is a perfect country for biking, with its gentle topography and well developed cycle path network.

Camping sites have very high standards, or you can stay at a ‘Kro’, a countryside hotel with a restaurant.

Do not forget to also visit the Rainforest in Randers, about 25 km from Aarhus, where three large glass cupolas are filled with rain forest plants, buzzing with the sounds of parrots, bats and monkeys.

You can find out more about visiting the area by following the links at the end of this article.

Moler is mainly found around Limfjorden in north-west Denmark, because the diatomites were only deposited in a narrow belt from Limfjorden into the North Sea, probably due to local upwelling of rich nutrient water. Diatomites have a very high porosity, and can therefore be dried and used to fabricate thermal isolation plates for buildings – and, because the rock absorbs water, as cat litter. The main excavation pits are found on the island of Fur and on northern Mors.

Moler has a characteristic expression, with beige-greyish diatomite constituting the main part, interbedded with thin bands of dark volcanic ash, carried from eruptions around the incipient Atlantic mid-oceanic ridge.

During Quaternary glaciations, glaciers from the North compressed the Moler into folds, and pushed it up to the surface. It therefore exhibits sharp folds and faults, beautifully enhanced by the interchanging light and dark layers.

Dramatic folding in the Moler, with interbedded light grey diatomites and darker volcanic ash layers. (Source: K. Eig)

Life in the Triopics

Fossils have made the Moler famous among palaeontologists, as the sediment has provided spectacular preservation of even the most delicate fish, insect and bird remains. The thin wings of insects have been preserved along with their colours, and several birds have feathers. In addition, there are beautifully preserved turtles, sea stars, crabs, and crustaceans, which together provide a detailed window into Denmark 55 million years ago.

At that time, Denmark was at a latitude of around 56° north, only one degree south of its present position – but the climate was considerably warmer. In the earliest Eocene, sea levels were low, and only a local sea incised Denmark from the North sea. The Atlantic spreading ridge had started separating the continents, and ash from those eruptions regularly rained over Denmark. Lack of circulation in the narrow sea led to anoxic conditions, and over a few hundred thousand years thick clay was deposited in the inland sea, which was estimated to be around 200m deep. This oldest clay, called the Stolleklint Ler (ler means clay in Danish) contains only marine fossils, and many of the preserved fish found in it are equivalent to tropical fish today.

Moving into the Lower Eocene, sea levels rose and provided a connection to the opening Atlantic Ocean. The climate became somewhat colder, but still subtropical. The shifting tectonics then directed currents towards the central North Sea and northern Denmark, which is believed to have resulted in an upwelling and blooming of the planktonic diatoms. Paradoxically, the rich nutrious sea in turn created large quantities of organic matter, which as they decayed that they created anoxic conditions on the seafloor. The diatomic layer, interbedded with ash beds, is the Moler proper, which has the stratigraphic name of the Fur Formation.

Fur formation. (Source: K. Eig)

Limfjorden in north-west Denmark. (Source: K. Eig)

Fish, Birds, Turtles…..

Fish are, naturally, the most prominent and numerous of the fossils, and more than 75 species have been identified. The most common in the lower horizon, the Stolleklint Ler, is a small herring-like fish, while the Moler is dominated by a small argentine. Sharks are represented only by teeth and a few calcified vertebrae. The remaining fossils are boned fish species, comprising both modern and more primitive ray finned fish, many of which today are found in tropical seas. Among the fossils are eels, tarpons, perches, mackerel, pipefish, sand eels, morays, and blowfish. This last is a spiked tropical fish that can blow up its body to a ball; in Danish it is accurately named the hedgehog-fish! One amazing fossil shows a redfish attempting to swallow an argentine its own size – thus sealing its fate. Flatfish, however, are absent, probably due to the anoxic bottom conditions.

The fossil turtle known as, Luffe – the baby sea turtle. (Source: K. Eig)

The most beloved and spectacular fossil from the Moler is a complete baby sea turtle. Even the soft tissue on the paddles and along the shell is preserved. Nicknamed ‘Luffe’ (Luffe can mean two things in Danish: It can be a noun, where a “luffe” are the paddles of marine mammals like seals, or a verb, basically meaning “move slowly”), it has become a mascot for both the Moler museum and fossil loving kids.

This sea was, however, not very far from the shore. Fossils of birds, insects and plants provide a fascinating look at the life on that land.

Over 30 different species of birds have been found, and they are solely terrestrial. No marine birds have been found, which is something of a mystery, but may stem from the fact that marine birds are unlikely to drown even if they are carried far offshore by the wind. Among the birds found are those similar to today’s tropical and subtropical wrens, trogons, turaco and tree swifts – and the bone of a parrot! The most complete skeleton is similar to a kingfisher, and has a belly full of small fish remains. Among larger birds are ones that resemble flying ostriches or cranes. The bird fossils of the Moler shows one of the largest variety in fauna found after the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary, and therefore provide a glimpse into the early evolution of modern birds, suggesting that their main shapes evolved quickly after the K-T catastrophe.

Insects are even more varied, with over 200 species: butterflies, cicades, flies, grasshoppers, wasps, dragonflies, crane flies, mosquitoes, cockroaches… Notably, all are winged, suggesting that only flying insects had been caught by the wind and carried out to sea. Large winged ants in the lower Stolleklint Ler suggest that the seashore was closer during the lowstand period.

Plant remains, mainly twigs and bits of wood, have also drifted out to sea. Among them is an eight meter long trunk, which probably belongs to the sequoia family. The plant material also includes remnants of pines, maple seeds, ginkos and water ferns.

Exceptional preservation of a shoreline bird fossil. (Source: K. Eig)

Danekræ a Badge of Honour

Altogether, the fossils paint a vivid picture of the landscape onshore: butterflies and cranes suggest a savannah-like lowland, while trunks of trees and the tree-dwelling birds show that it was draped with woods, presumably concentrated around wetlands and rivers bright with dragonflies and kingfishers.

Coastal cliff, part of the Fur Formation on the Danish island of Fur, showing clay and ash-layers. (Source: Rene Sylvestersen)

The fossil treasures from the Moler have been known for more than a hundred years. Two local museums exhibit the highlights. The local museum on Fur has a large display of fossils in addition to local history displays, while the Moler museum in the north of the island of Mors is entirely dedicated to the Moler fossils. Both museums also tell the history of the geology and palaeogeography in the Eocene. Displays are somewhat old-fashioned, but informative and they give a good impression of life in Eocene Denmark.

Denmark has a unique approach to preserve its fossil heritage. In 1985, a German tourist sent a postcard to the Fur museum, stating that he had found a large fossil fish, brought one slab of the fossil home and dug the other slab down at a location, which, like a pirate’s treasure map, he had marked on the photo on the postcard. The slab was soon found and prepared, and researchers realised that this was a remarkable fossil.

It was recognised that it was necessary to secure such scientifically important fossils for the future, and in 1989 a law was passed which demanding that all important fossils must be handed over to the state. If examined and found scientifically significant, they would get the status of Danekræ – loosely meaning ‘Danish animal’ – and the founder would be paid the value, and be recognised as finder. The law also covers meteorites and important mineral specimens.

The Danekræ law has had the fortunate effect of many collectors competing for the honour of finding such specimens. 676 fossils have been accepted as Danekræ, around half of which came from the Moler sediments.

Several pits are still in operation, and the Moler also outcrops along the Limfjorden waters, therefore new specimens are regularly unearthed. Searching is encouraged, and the museum on Mors even rents out geologist hammers to those who want to try their luck! However, the fossils with the best preservation, including feathers and bones, are found in concretions, cemented by bacteria-precipitated calcite. These are very tough – you will need to bring a sledgehammer to crack them.

Bispehuen (‘Bishop’s hat’), a strongly folded, pillar of Moler in an abandoned pit on Fur. (Source: K. Eig)