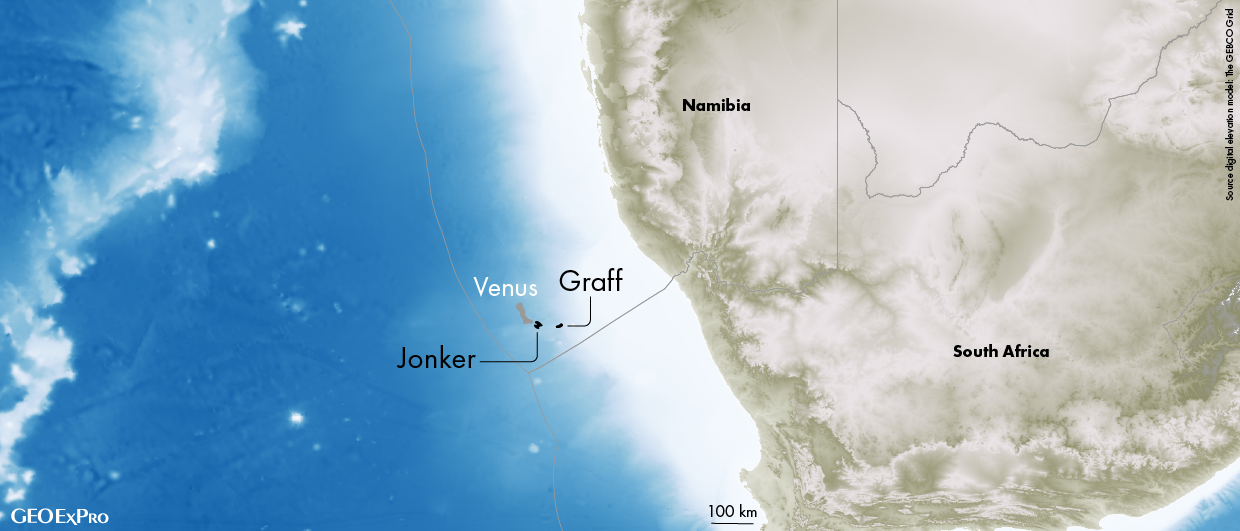

This week, Namibia’s petroleum commissioner Maggy Shino announced that Shell has thus far discovered 200 million barrels of recoverable oil at Graff and 300 million barrels of recoverable oil at Jonker.

These figures are significantly lower than previous estimates. In 2022, Upstream reported that Graff’s recoverable oil resources had increased to about 400 million barrels, and even a 500 million barrels figure was mentioned in the same year. Recoverable volume estimates for Jonker seem harder to to get by, but the latest estimates also seem to have come down.

At least for Graff, that means a 50% reduction or more in recoverable volumes.

What could be the geological explanation for this?

Unless you work for Shell or a service company associated with the projects, you will not find out what the exact reason for the downgrade is. However, during a conversation at a conference last year with a person with knowledge on the matter, I did get a hint about a possible explanation.

And that explanation is “a mineral”. That’s all I heard. But it is telling. I would not be surprised if that mineral is illite, well-known for clogging up pore space and thereby especially reducing the permeability of the reservoir. Yes, it does go against the title used for this article “Like a train”, Oil flows at supercharged rate from Shell’s ground-breaking Namibia probe”, as reported by Upstream in May last year. This leaves the impression of a multi-Darcy reservoir for sure. But reduced permeabilities have a knock-on effect on recoverable volumes, so it would still be a logical candidate.

Would it be possible that Graff and Jonker represent discoveries that show lower permeabilities than what most deep-water developments ideally need? It would be a very interesting test case for the economic viability of these fields, as many in the industry argue that high permeabilities are required for these types of projects to fly. At the same time, we have seen that the Gulf of Mexico has allowed relatively low permeability deep-water discoveries to be developed thanks to the presence of infrastructure, thick reservoirs and a favourable tax regime.

And it is the latter that the Namibian government has control about. It could be this very aspect that negotiations between the operators and the government are focused on at the moment. Ultimately, the plan is “to accelerate developments of the oil finds in Namibia”, Maggy Shino said. Let’s watch this space.

See also: The future lies in low-perm reservoirs – not only in the desert but possibly in deep-water too