The petroleum industry is going through a transformative period related to intensified digitalisation, economic pressure and an increasing degree of environmental regulation. A successful transformation requires innovative technology and business models, ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking and solid domain expertise. This cannot be achieved, or at least will not be efficient, by use of in-house expertise and resources alone – it needs input from the world outside. Possibly the most natural partners in this process are universities that can offer both the drive and creativity of students and young staff, as well as the scientific and domain excellence of seasoned employees. The industry has a long tradition of collaboration with universities but has not yet unlocked the full potential in transforming knowledge and technology into practical solutions: new products, services, processes or industry standards – i.e. innovations. Despite the establishment of a host of new innovative start-up companies, often with roots in academia, organic technology adoption and transfer as a part of university–industry collaboration can be enhanced.

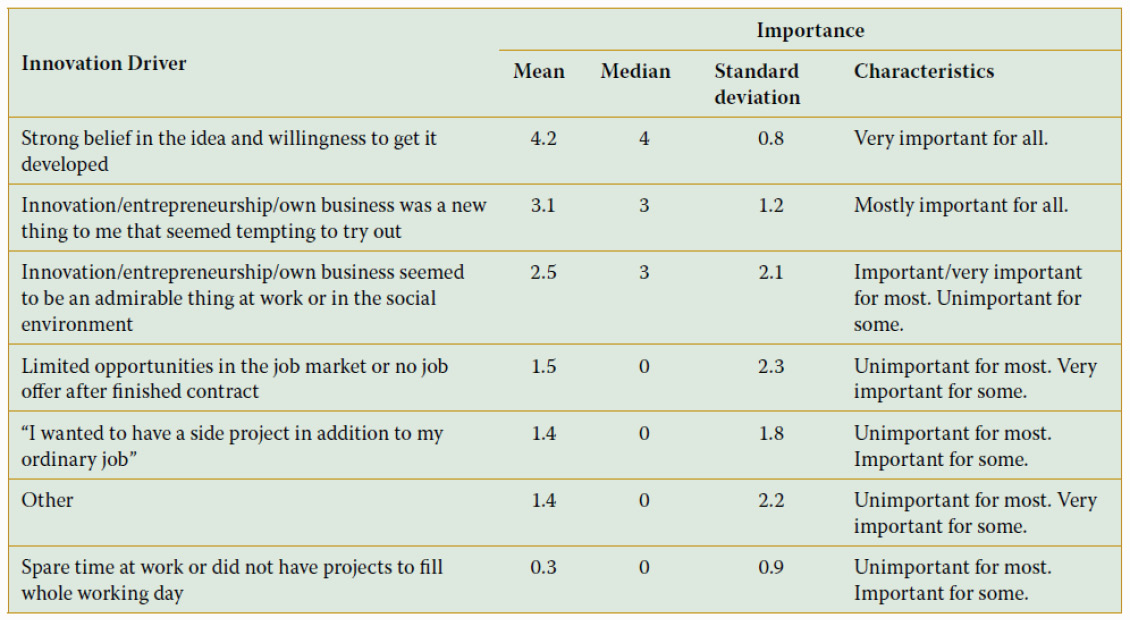

Improvement of the technology and innovation transfer from universities to the industry is in the interest of both parties. It can create market-relevant projects for researchers and give access to genuinely novel ideas and technology for the industry, all at relatively low cost. However, unlocking the full potential of collaboration requires actions from both sides. Here, we challenge the status quo and attempt to answer the question: what conditions can favour the creation of more relevant research-based innovations that support transformation of the petroleum geoscience industry? Our reflections are supported by views voiced in numerous discussions and interviews with employees at the Department of Geoscience and Petroleum (IGP) at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) over the last two years. In addition, our views are supported by a survey performed among 13 inventors from IGP in early 2020 (see table).

Importance of Industry Feedback

Our survey shows that the most important driver for pursuing innovation work by researchers is a deep belief in the commercial success and novelty of their own ideas. This requires an ability to spot commercial potential and usefulness beyond scientific publications. We see, however, that few researchers can actually identify the innovation potential or believe in their idea’s commercial success from the very beginning. Most academics need to get some advice on initial idea refinement, market/user fit and ways of transferring ideas to potential users.

Researchers also need to test the value and novelty of their own work by validating it with the users. Industry representatives have the best overview of their needs, know of existing solutions and their respective disadvantages. Without the involvement of the industry, researchers could not suggest relevant solutions, being unaware of trends, business focus and technical framework.

University–Industry Co-Creation on Innovation

In practice, relevant innovations are born as a part of synergetic idea exchange between inventors and potential users of the invention – in our context, the industry – rather than born in a vacuum. More and more innovations are being created as a part of open inter-organisational collaboration (‘open innovation’) including the oil and gas sector. Many major oil companies have changed focus from outsourcing R&D to more open innovation, giving them the opportunity to acquire new, future-relevant competence through collaboration. An example is the open innovation initiatives of Eni, where multiple external collaborators have been engaged by the company since the early 2000s. In a university–industry context, collaboration that relies on synergetic cooperation and deep industry engagement favours the development of new ideas and technological solutions.

Moreover, openness in data and results can strengthen development of genuinely innovative solutions thanks to broader participation in the innovation process. Developments in this direction have been made in the industry recently, chiefly thanks to a willingness from oil companies to open up traditional knowledge silos. Equinor’s open-source code repository, for instance, facilitates new contributions to the code and its use by external parties, including academia. Another good example of enhanced interplay between academia and industry that helps create innovative digital solutions are ‘hackathons’. These are creative problem-solving events that have been supported by major stakeholders such as the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate and the UK Oil and Gas Authority, as well as multiple oil companies. In recent years, participants of these hackathons have created thousands of novel solutions and several million lines of open-source software code used in digital advancement and energy transition.

Our survey shows that researchers are open to trying new forms of knowledge transfer, such as entrepreneurship or innovation work. This was mentioned as our respondents’ second most important driver for innovation. The main prerequisite here, however, is time to pursue collaboration, experimentation and application of the research results beyond traditional scientific deliverables. Academia, including open-minded employees and students, is an ideal space to explore the possibilities that lie within open innovation. Furthermore, open access is more of a university ideal and open access to data is receiving increasing focus in research and also by governmental funding institutions.

Access to Resources Vital

Curiosity and creativity are favoured by safe environments, low personal risk and incentives. Incentive systems and ownership of intellectual property for academic work are different across countries and universities. However, at many universities scientific staff are not sufficiently incentivised to pursue innovation work, as their achievements are assessed by scientific publications, while technology transfer and innovation work are rarely taken into consideration. We cannot therefore expect temporary researchers to pursue extra innovation work if their work is assessed on traditional scientific merits only. The same applies to permanent staff who are fully booked with their primary tasks such as teaching, supervising and research. As a result, some universities have introduced special incentives that can be used solely for pursuing innovation work. For example, NTNU has established several internal incentive schemes to promote and facilitate both technology innovation and market validation, which have supported multiple innovators in the petroleum and geoscience domains. There are also examples of similar incentive schemes in the Norwegian context, including specific calls funded by the Research Council of Norway.

Although a lack of jobs was not found to be a major innovation driver according to our survey, it was still considered very important for some temporary employed researchers, typically PhD and post-doctoral candidates. Innovation work sponsored by a university can be a positive career move for those who have not yet secured a new job after their temporary research contract runs out. This should be regarded as an opportunity for universities to put into practice ideas and technology developed during such research projects that might otherwise not be used. To utilise this opportunity, researchers need to have access to financial schemes and support for early phase technology development from universities, as previously mentioned, or to have easier access to resources from the industry, which has recently started investing in creative teams, offering both financing and access to resources such as mentors and workshops. One of the examples is the Equinor and Techstars start-up accelerator for those “who work on disruptive solutions within oil and gas, renewables, new business models and digitalisation”. Another example is the Oil and Gas Technology Centre TechX Accelerator programme and their Innovation Hub.

Social Recognition and Role Models

The third most important innovation driver indicated by the survey is high social recognition of those who pursue innovative work. Geoscientific and petroleum communities know that digitalisation, energy transition and transformation of the oil industry need innovative ideas and creative specialists who can think outside the box. Entrepreneurship and innovation have become important terms not only in the geoscience and petroleum communities but also in the broad public sphere. Universities need to promote innovative thinking, show success stories and facilitate dialogue with successful innovators. Entrepreneurial professors have a very strong impact on their academic environments and can act as examples for other employees, so ‘investment’ in the top academic staff is possibly one of the most effective ways to boost innovative thinking in scientific environments.

A Way Forward

Results based on the survey and extensive discussions made at IGP NTNU, suggest that innovation from the personal perspective of researchers is driven by belief in the idea, curiosity about the practical application of research and appreciation for innovation work in an academic environment. It also shows that researchers need the opportunity to validate their own ideas with potential users of their innovations and that academia–industry co-creation is a very suitable environment for creating relevant technological advances. Efforts should be made to enhance synergies between researchers and industry professionals on a technical level and researchers need to have access to a range of different resources. Securing funding is important, but so is access to mentors and the need to learn about technology commercialisation.

Of course, some of these resources can be found today, in different forms, and from different sources. In our opinion however, there is potential for improvement in university–industry collaboration aimed at the creation of future-relevant innovations. As such, we see the ideas expressed in this article not as a clear-cut way forward, but rather as an invitation to a more detailed discussion on the topic of creating innovation for a changing geoscience and petroleum industry. And as with any good innovation, we need user feedback going forwards – or, in our case, the industry perspective.