With Equinor this week awarding a multi-well contract to COSL Drilling Europe to have four additional wells drilled on Statfjord Ost from 2023 onwards, in addition to an option for another five wells to on Statfjord satellites, it looks as if drilling these old Brent fields is as lucrative as it has ever been. At least, in the Norwegian sector.

This begs the question, how does drilling activity in the UK and Norwegian Brent provinces compare? There is a lot of talk and media attention towards exploration and appraisal drilling, but ultimately the amount of development wells being drilled in a basin may be as good an indication of the attractiveness of the area as anything.

Brent UK versus Brent Norway

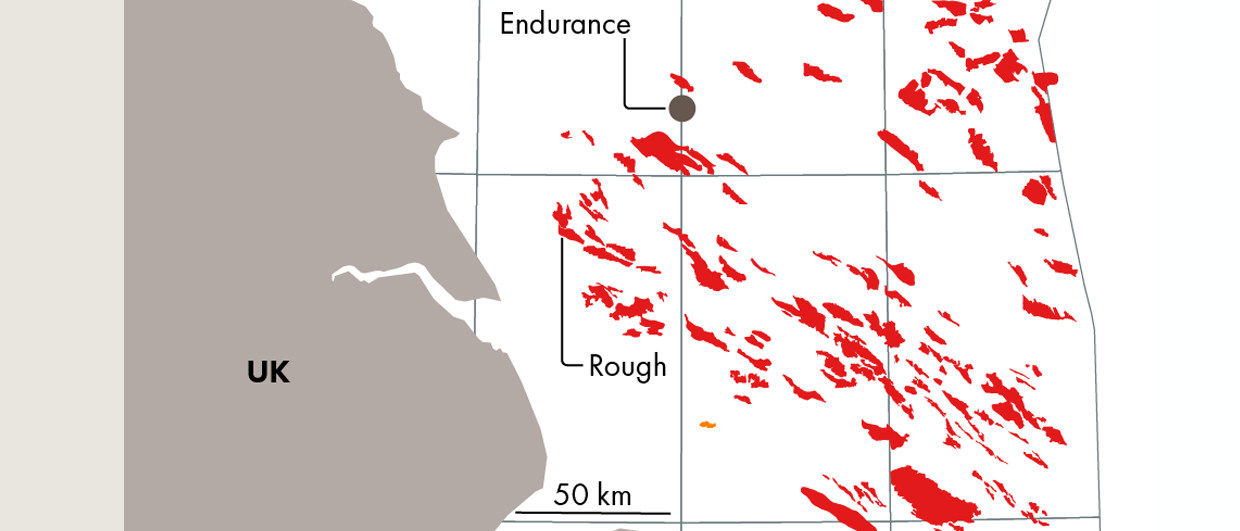

For that reason, we are today looking at the number of development wells drilled in the Brent province of both the UK and Norwegian sectors. Is there be a marked difference? Fields in both sectors were discovered around the same time and were put on production around the same time, so in that respect it may be expected that a similar pattern can be observed. We only look at the number of development wells drilled from 2014 onwards to capture the start of the major downturn that started in the middle of that year.

There is a stark contrast between the two sectors, as the graph below illustrates.

The first thing that catches the eye is the sheer number of Brent development wells drilled in the Norwegian sector compared to the UKCS. In the former, a minimum of 50 wells a year was drilled in every year from 2014 onwards, whilst in the UKCS 2019 marks a “top year” of a total of 19 wells drilled. And for reference, the number of Brent fields in which drilling took place in both sectors is much more comparable; 24 fields in Norway compared to 19 in the UK.

Another interesting aspect of this graph is the only minor small dip in number of development wells drilled in Norway following the start of the downturn in 2014, if the dip in numbers that only takes place in 2017 is indeed still related to the oil price crash in the first place. At the same time, the UK sector does show a much more rapid response to the crash, with a local minimum of 5 observed in 2017.

And just when confidence was returning slightly in the UK post 2017, the pandemic hit and slashed the number of Brent development wells in the UK to an absolute minimum of 3. In the meantime, the Norwegians ploughed on and no effect of the pandemic can be seen in their numbers at all.

Then the question is, why is there such a difference between the two sectors? It is not down to recent exploration success, as most of the fields have been known for decades. Is it due to different ownership? Equinor continues to be by far the main player in the Norwegian Brent province. In contrast, in the UKCS Brent province, ownership is much more fragmented and fields have also changed ownership more frequently. Has this patchwork of ownership been detrimental to long term production? It is certainly worth another analysis.

HENK KOMBRINK