As announced last week, the new German coalition plans include a potential ban on new exploration licences being issued in their part of the North Sea.

Is this a surprise? Probably not, given the trend that is currently unfolding with more countries announcing similar plans – Greenland, France, Ireland and Spain.

Is it a far-reaching measure? No. Exploration in the German part of the North Sea has not been particularly vibrant over the past years, maybe even decades. And in contrast to Denmark, where a cluster of big fields were found before exploration tailed off in recent years, the German part of the North Sea has never really seen a boom in exploration and production.

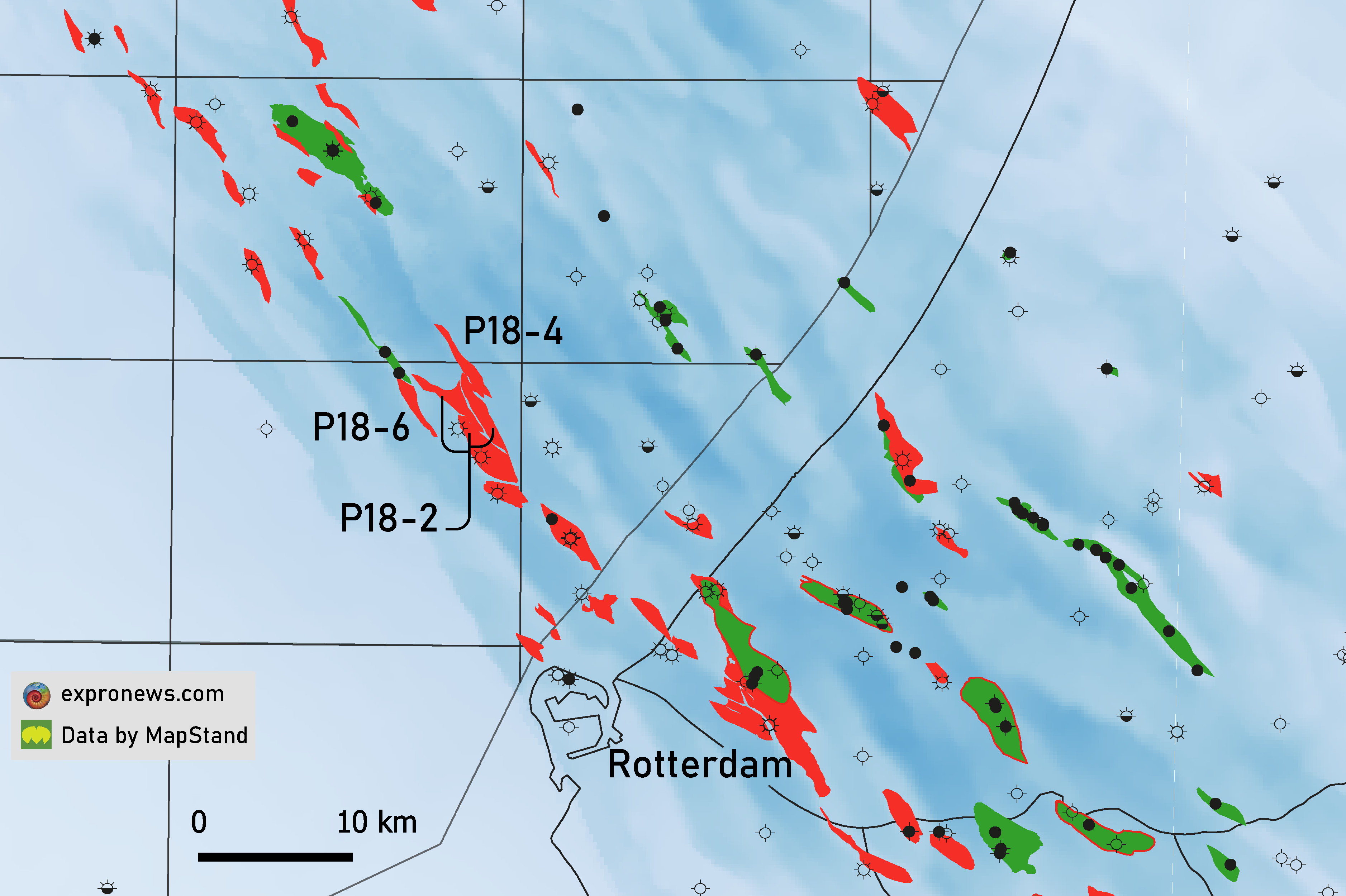

The only fields in the German North Sea sector currently producing are Nordsee A6/B4 and Mittelplate close to the coast. As the map below shows, there are a number of gas discoveries in unlicensed areas, but the problem related to these supposedly (basal) Rotliegend finds is likely related to elevated nitrogen concentrations and probably reservoir quality as well.

Why offshore?

The question that one should ask is this one: Why are the Germans intending to put a ban on offshore exploration and not on onshore activity? Wouldn’t it send a stronger, and more popular message to prevent any more drilling in people’s backyards?

One of the explanations for this is the federal nature of Germany. With each state being able to legislate for mining activities, introducing a nationwide ban is probably more complicated to organise even when most oil and gas fields are situated in the state of Lower Saxony.

In that sense, banning offshore activity may have just been the quickest way of implementing such a thing, and as alluded to above, the economic damage caused by the measure is probably quite limited if present at all.

The Netherlands

At the same time, as we reported on before, the Dutch government and a diverse group of industry and NGO stakeholders has earlier this year agreed that exploration for remaining hydrocarbons in the Dutch offshore is favourable in order to minimise the exposure to imported gas.

In contrast, the Dutch are making onshore operations more challenging, with the imminent closure of Groningen and lengthy procedures for other onshore developments.

Taking a high level view on this, at first glance it looks as if Germany is taking an opposite stance to the Netherlands through discontinuing licensing and therefore exploration. However, when considering the political systems and the fact that prospectivity in the German North Sea has always been more limited than in the Dutch sector, the apparent contrast is not as strong as it would seem.

HENK KOMBRINK