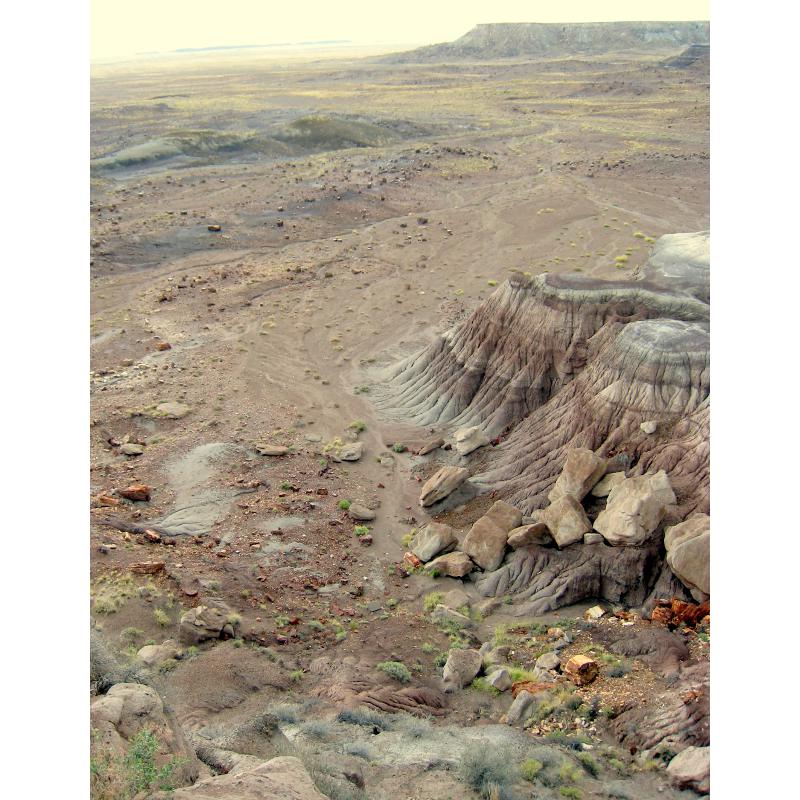

Petrified Forest National Park (PFNP), located in north-west Arizona, is renowned for its brilliantly colored petrified logs scattered throughout the red, brown, and white hills and bluffs. Two hundred million years ago, when the climate was much wetter and warmer than today, conifer trees once lined ancient waterways. Periodic flooding would uproot and bury these trees and over time, the wood was replaced by quartz that is tinted into a kaleidoscope of rainbow colors. But what may be even more remarkable than the beautiful petrified trees is the historical narrative that other ancient animals and plants, well preserved in the park’s strata, are telling us about the climate changes and evolution that took place in the Late Triassic.

The Chinle Formation, extensively exposed in the park and outcropping across much of the Colorado Plateau, is one of the most researched Late Triassic continental deposits in the world. Preserved in the strata of the PFNP is probably the best-studied terrestrial vertebrate faunas from this critical time in Earth’s history. This period is situated right between the Permian and the end of the Triassic mass extinctions. Detailed mapping of the strata has led to a new interpretation of the biostratigraphy and a recent core drilling project may provide more information to the history and climatology of this 20 million-year time frame.

Park History

People have known about the Petrified Forest for over 13,000 years. Camp remains, tools, and projectile points made from petrified wood have been found in this area, dating from just after the last Ice Age to historic times. The Spanish were among the first Europeans to visit the area in the 16th century, but with no mention of the petrified wood; they were concentrating their efforts on finding routes between colonies along the Rio Grande River to the Pacific Coast. Within the park, Spanish inscriptions from the 1800s can be seen on some of the rocks.

The south-west became part of the US territories in the mid-1800s. In 1853, US Army Lt. Amiel Whipple was exploring a route along the 35th Parallel when he came upon a sandy wash in the Painted Desert that had deposits of colorful petrified wood along its banks. Whipple named it Lithodendron (‘stone tree’) Creek and was the source of the first published account of petrified wood in what would become PFNP. Settlers followed the 35th Parallel route and grazed cattle, sheep, and horses in the park until the mid-20th century. What started out as a wagon road in 1857 and a stage line in 1874, became the famous Route 66 in 1926. This route now is Interstate 40, a major US east-west connection, first crossing the park in 1958.

Once the area was discovered, the petrified wood began disappearing. In spite of regulations and fines, resource managers found that visitors could not resist taking these beautiful rocks. Congress turned down a bill to designate it a park in 1895. Conservationist John Muir explored the area in 1904 and 06. Whether or not Muir had any influence to protect this unique area, President Theodore Roosevelt established Petrified Forest National Monument in 1906 and in 1962 the US Congress made it a national park. More recently, the park boundaries have been expanded, more than doubling its size from 37,851 to 88,437 hectares.

Focusing on the Late Triassic

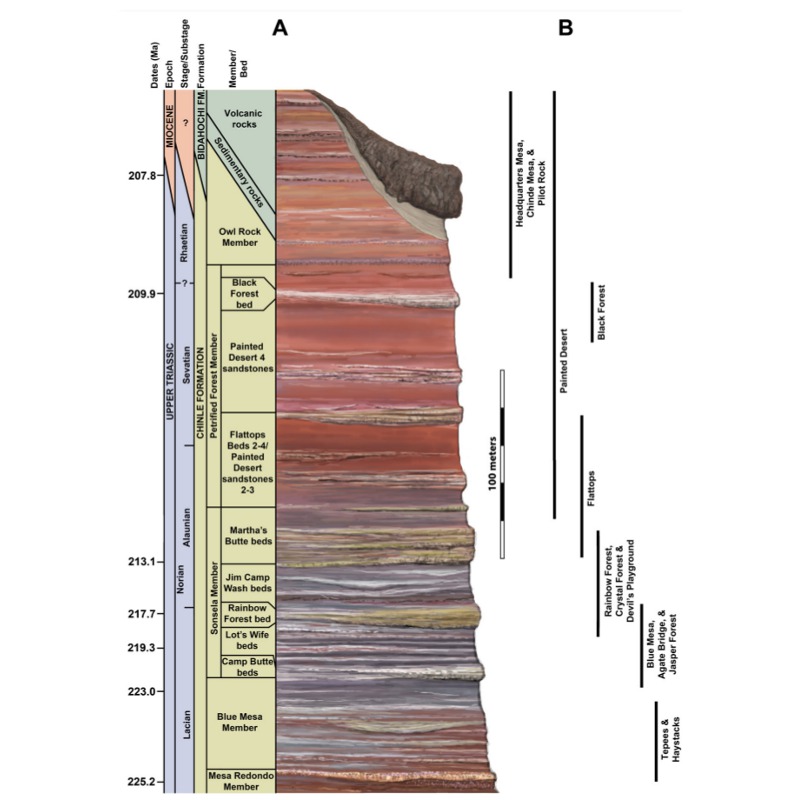

Lithostratigraphic column for Petrified Forest National Park. (Source: Arizona Geological Survey)The Triassic Period in Earth’s long history holds a particularly prominent position; it was a time of great change and rejuvenation after nearly 90% of the planet’s species died off at the end of the Permian Period. New creatures that included rodent-sized mammals and the first dinosaurs became part of this new, growing diversity. It was also a time when its landmasses, originally linked as one supercontinent called Pangaea, had by the end of this period started breaking apart. The Late Triassic ends in a mass extinction that ushered in a time when dinosaurs would dominate the earth. Leading up to that mass extinction was an earlier faunal and floral transition, or even possibly a smaller extinction, that corresponds with a change in climate.

Lithostratigraphic column for Petrified Forest National Park. (Source: Arizona Geological Survey)The Triassic Period in Earth’s long history holds a particularly prominent position; it was a time of great change and rejuvenation after nearly 90% of the planet’s species died off at the end of the Permian Period. New creatures that included rodent-sized mammals and the first dinosaurs became part of this new, growing diversity. It was also a time when its landmasses, originally linked as one supercontinent called Pangaea, had by the end of this period started breaking apart. The Late Triassic ends in a mass extinction that ushered in a time when dinosaurs would dominate the earth. Leading up to that mass extinction was an earlier faunal and floral transition, or even possibly a smaller extinction, that corresponds with a change in climate.

For over 50 years, many researchers in this area have focused on the Late Triassic. Interpretations concerning fossil transitions and climate change have been made that had regional and even global implications. However, one of the big questions that was not being answered was just when did this change occur?

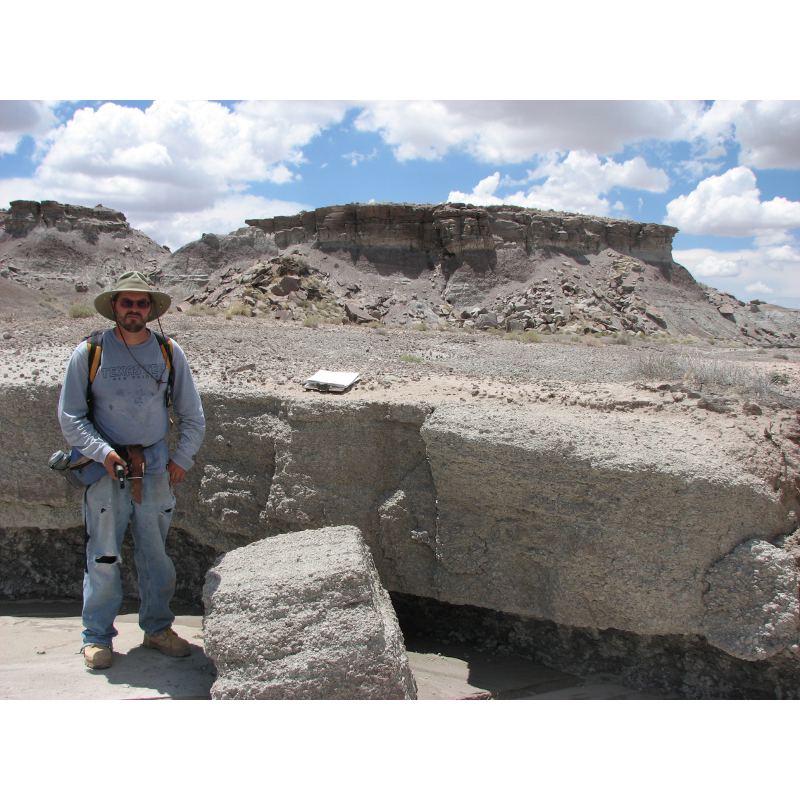

A stunning natural park full of vistas evocative of ancient landscapes. (Source: Thomas Smith)This was just one question bothering William Parker, Chief Paleontologist at Petrified Forest National Park. “Despite over 150 years of study, the stratigraphic distribution of fossils in Upper Triassic deposits of the south-western United States is still not well understood,” says Bill. “When I started field work here in 2001, I found certain beds were incorrectly correlated, leading to errors in placing fossil and sampling localities within the stratigraphic framework. I knew that to make sense of what the fossils were trying to tell us, we needed to accurately relocate and plot all known Upper Triassic vertebrate fossil localities. We started our detailed remapping and relocation of fossil occurrences in the southern portion of PFNP.”

A stunning natural park full of vistas evocative of ancient landscapes. (Source: Thomas Smith)This was just one question bothering William Parker, Chief Paleontologist at Petrified Forest National Park. “Despite over 150 years of study, the stratigraphic distribution of fossils in Upper Triassic deposits of the south-western United States is still not well understood,” says Bill. “When I started field work here in 2001, I found certain beds were incorrectly correlated, leading to errors in placing fossil and sampling localities within the stratigraphic framework. I knew that to make sense of what the fossils were trying to tell us, we needed to accurately relocate and plot all known Upper Triassic vertebrate fossil localities. We started our detailed remapping and relocation of fossil occurrences in the southern portion of PFNP.”

Recognizing that there were multiple, look-a-like sandstones in this fluvial environment was one of the keys in helping Bill and Jeffrey realize that there were correlation problems with previous lithologic studies. Most of the previous researchers were content with the coarsely resolved stratigraphic framework when using the vertebrate fossils as biochronologic indicators.

Now, knowing that there were problems with the area’s lithostratigraphy, and particularly correlation errors within the Sonsela Member of the Chinle Formation, they went back to the basics by ‘walking outcrops and contacts, checking section measurements, and mapping the area in detail’. The process of getting ‘back to the basics’ can be difficult and sometimes forgotten when a lot of data already exists. Whether using outcrop or subsurface data, it is good to look back and make sure the basic data is sound (their premise in doing this work) so that the models made from that data are equally as sound.

A new, comprehensive geologic map of the area was published in 2012. Armed with accurate sample localities, measured sections, and properly correlated beds, the two park paleontologists could begin to unravel the overall geology and history of the area in yet another ‘revision’.

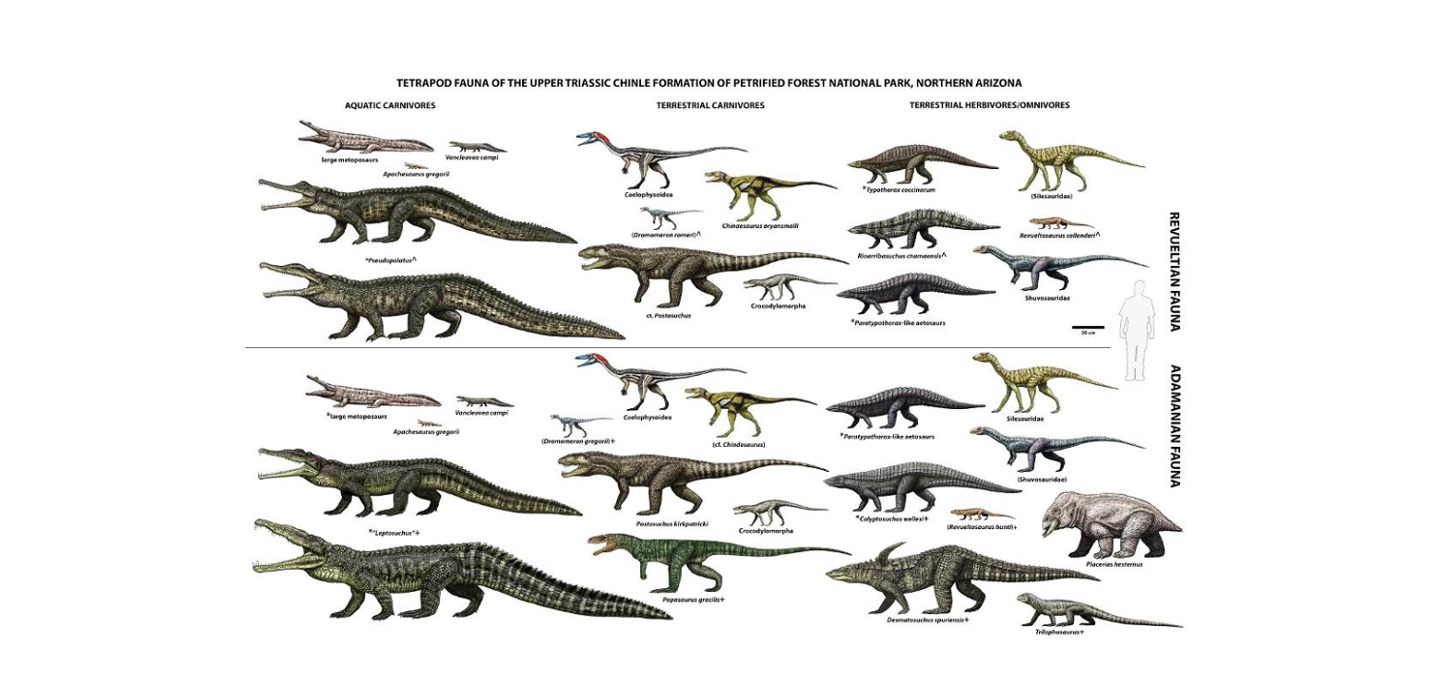

Adamanian and Revueltian tetrapod faunas, Northern Arizona. Seven taxa from the Adamanian do not occur in the Revueltian while the four new taxa are found in the Revultian. (Source: W. Walker, NPS)

Adamanian and Revueltian tetrapod faunas, Northern Arizona. Seven taxa from the Adamanian do not occur in the Revueltian while the four new taxa are found in the Revultian. (Source: W. Walker, NPS)

Re-Revisiting History

“If the basic superpositional relationships of the fossils, mag-strat samples, volcanic minerals, and lithologic units used to acquire this information [that is used to derive a historical narrative] are misunderstood, the interpretation derived from them will be inaccurate,” says Bill Parker. “The order and timing of events will be wrong, and any attempt to understand cause and effect will be in vain.”

Along with the fauna and flora that populated the area, one of the keys enabling Bill Parker and Jeffrey Martz to understand when the climate started to change was the location of the ‘persistent red silicrete’ bed marking the Adamanian-Rivueltian transition. They were able to place this within the lower Jim Camp Wash beds in the Sonsela Member, rather than at the Tr-4 unconformity as other researchers did. (Source: Thomas Smith)The well-exposed and studied rocks and fossils within PFNP have yielded interpretations that have been applied to regional and global climate and faunal changes. Previous studies of this area have hypothesized a Late Triassic (Tr-4) area-wide unconformity and put an important faunal transition, called the Adamanian-Revueltian transition, at this time point. Previous studies also concluded a significant overlap of the Adamanian-Revueltian faunas. Because of this faunal overlap, these same studies clearly reject the idea that a global tetrapod extinction occurred within the Late Triassic.

Along with the fauna and flora that populated the area, one of the keys enabling Bill Parker and Jeffrey Martz to understand when the climate started to change was the location of the ‘persistent red silicrete’ bed marking the Adamanian-Rivueltian transition. They were able to place this within the lower Jim Camp Wash beds in the Sonsela Member, rather than at the Tr-4 unconformity as other researchers did. (Source: Thomas Smith)The well-exposed and studied rocks and fossils within PFNP have yielded interpretations that have been applied to regional and global climate and faunal changes. Previous studies of this area have hypothesized a Late Triassic (Tr-4) area-wide unconformity and put an important faunal transition, called the Adamanian-Revueltian transition, at this time point. Previous studies also concluded a significant overlap of the Adamanian-Revueltian faunas. Because of this faunal overlap, these same studies clearly reject the idea that a global tetrapod extinction occurred within the Late Triassic.

Martz and Parker recognized that previous studies relied on poorly documented correlations to make important biostratigraphic conclusions, so they concentrated their initial efforts on accurately mapping and correlating stratigraphic relationships in the park. This led to some interesting discoveries; they were able to clarify the local biostratigraphy with some profound regional and global implications. (It should be noted biostratigraphic ‘revisions’ from other areas have been shown to have comparable problems. Jeffrey Martz did a similar study of the Upper Triassic Dockum Group of West Texas that resolved conflicts in the lithostratigraphic and biostratigraphic correlations for that region.)

Now Parker and Martz can actually constrain where, in the strata, the changes happened. They showed that a single unconformable horizon within or at the base of the Sonsela Member, which previously was traced across the entire western United States (the Tr-4 unconformity) probably does not exist. The significant overlap between the Adamanian and Revueltian faunas has been rejected and does not occur at the Tr-4 unconformity. They know this by accurately locating samples and important boundaries within the correct stratigraphic levels.

These two paleontologists found a fossil turnover at the Adamanian-Revueltian boundary occurring at a time of climate change for the region, from relatively humid and poorlydrained to arid and well-drained. The vertebrate fossil transition occurs with the floral changeover based on recent palynology studies, and age constraints put this at about the same time as the Manicouagan impact event. The Manicouagan Crater is located near Quebec, Canada and is one of the oldest and largest impact craters on Earth dated at 214 million years ago, in the middle Late Triassic. Their studies also show that dinosauromorph diversity has held constant across the Adamanian-Revueltian transition, indicating it probably did not lead to the rise of dinosaurs in North America.

While these revisions may not seem major, in the realm of biostratigraphy they loom large. Attention to detail has paid great dividends to our understanding of the Late Triassic. In the oil and gas business, going back to basics and using constrained and accurate data to model a prospect is a foundation that can make the difference between a duster and a gusher. Remember, not all ‘Flattops One sandstones’ correlate.

Useful link:

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to William Parker, paleontologist, and William Reitze, archeologist, for their help and information.