The screams of a group of Guanacos suddenly catch our attention. We look around us and embrace the wilderness of the southern Patagonian landscape. Anchored to the saddle, the feet pushing automatically on the pedals, we are slowly cycling from Puerto Natales on the dusty road that meanders through the southern Andean foothills. Ahead of us, fabulous, majestically snow-covered peaks stick out above the horizon and dominate the Argentine Pampas: the Cordillera del Paine is attracting us like a magnet; it is one of the highlights of our nine-month journey.

At dusk, after a seemingly endless day of cycling, we reach the gate of the Torres del Paine National Park. A red fox crosses the dirt road and looks at us before disappearing. Condors glide high over the hills without any wing beats. The Cordillera del Paine is impressive, with dramatic cliffs rising almost three kilometres above the foothills. But the most striking feature is the colour of the mountain: the cliffs exhibit a prominent white band, almost a kilometre thick, extending across the peaks of the massif.

History of the National Park

The landscape and the geographic situation make the Cordillera del Paine an emblematic feature of the area. Located at the transition between the Andes and the Patagonian steppes, it dominates its surroundings, and it can be seen for large distances from the east, yet is easily accessible for tourists. The Cordillera del Paine also stands at the gate of the Southern Patagonian ice field, the third largest ice cap in the world.

Archaeological remnants show that this remote ‘end of the world’ region was permanently inhabited by indigenous tribes as far back as the sixth millennium BC, although Europeans only explored the Cordillera del Paine for the first time in the 1870s. Since then, German and British colonists have occupied the surroundings, founding large sheep and cattle farms. Because of the rough climatic conditions, this farming considerably impacted the fragile, wild ecosystems of the area.

The Chilean government became increasingly aware of the unique value of this wildness and created the Torres del Paine National Park in 1959. It was designated a World Reserve of Biosphere by UNESCO in 1978. The Park’s wilderness and breath-taking scenery attract growing numbers of tourists from all over the world: in 2010, almost 150,000 visitors enjoyed the marvels of the park, with tourism becoming the mainstay of the economy of Puerto Natales and the entire region.

Geology: Sea, Magma and Ice

The Cordillera del Paine is dissected into several mountain groups. The westernmost Paine Grande is the highest of the range at 2,884m. The most prominent peaks are those of the Cuernos del Paine (Paine’s horns), which are separated from the Paine Grande by the deep glacial Vallé Francés. Nestling in the heart of the range, the gigantic natural cathedrals of the Torres del Paine are the most famous highlight of the massif.

As mentioned, the most striking feature is the two-toned colouration of the mountains. A prominent white band is sandwiched between dark rocks, the contact between them being extremely sharp, as though cut with a knife. The dark rocks are Cretaceous turbidites and layered sandstones with local occurrence of conglomerates, deposited in the Magallanes Basin. The white rocks are the result of a widespread (10 km by 20 km, up to 2,000m thick) magmatic intrusion emplaced during the Upper Miocene (12.5 Ma). Although the intrusion looks homogeneous, it consists of a suite of igneous materials resulting from successive magmatic pulses of mafic to felsic composition. The dominant magma body is a granite laccolith (a sub-horizontal intrusion with uplifted overburden). The Torres del Paine intrusion is one of a suite of granite intrusions in Patagonia, the most famous of which is the dramatic Fitz Roy-Cerro Torre Peaks, a few hundred kilometres to the north on the Argentine side.

The laccolith is clearly visible at the Cuernos del Paine, where both the bottom (lower contact) and roof (upper contact) of the laccolith are perfectly exposed. In the cliffs here the visitors can even observe some ‘frozen’ falling dark blocks of the laccolith’s roof embedded in the white granite. The thickness of the laccolith means that the sedimentary host rock has been heated and metamorphosed, so that primary sedimentary layering is no longer visible in the vicinity of the intrusion.

However, these amazing geological features would have never been exposed without the combined contributions of Andean tectonics and glacial erosion. Originally deposited at the bottom of the sea, the sediments now crown nearly 3,000m-high peaks, the associated uplift being the result of the Andean orogeny. Evidence of the orogeny are prominent in the landscape, including stunning folds and faults. Finally, glacial erosion carved the deep valleys that dissect the Paine laccolith during the last glaciations. The retreat of the glaciers offered us this unique and wonderful heritage. In 2014, the current glacier retreat even uncovered a worldclass dinosaur graveyard contained in the Cretaceous sediments, including 46 specimens of nearly complete skeletons of icthyosaurus.

The Trek: ‘W’ Versus ‘O’

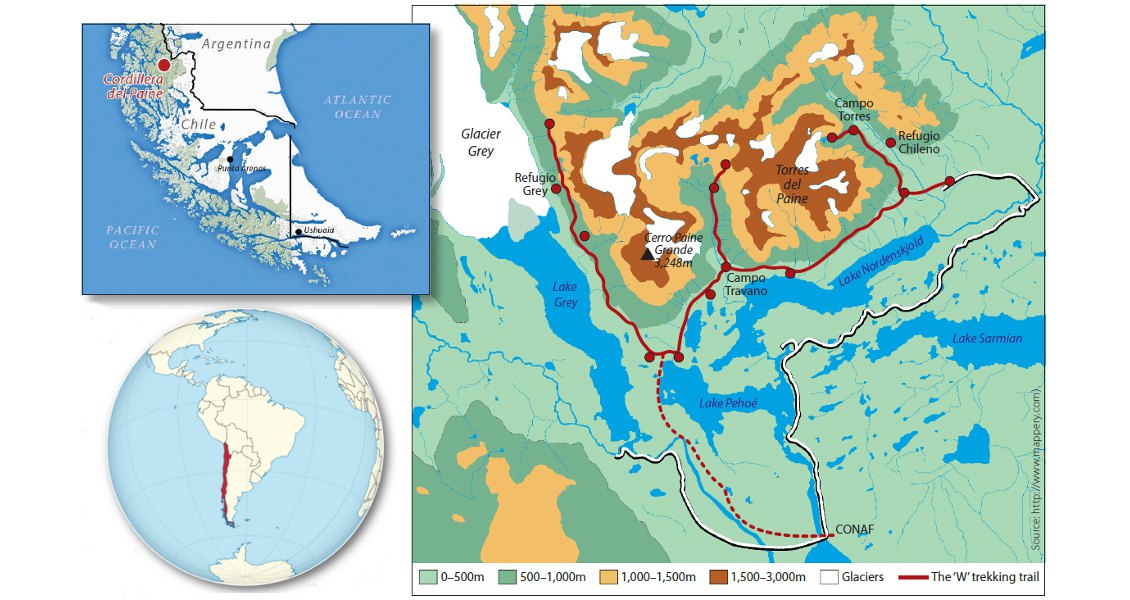

There are two main trekking options at Torres del Paine. The first and most popular is the four-day so-called ‘W’ itinerary, restricted to the southern flank of the range. The itinerary explores three valleys, each of them being one branch of a ‘W’, as seen on the map (above). The ‘W’ is usually crowded with tourists from all over the world. The other alternative, less popular but much wilder and more remote, is the six-to-ten-day so-called ‘O’ circuit, which extends the ‘W’ and makes the full loop around the Cordillera del Paine.

The ‘W’ trek starts from the administration huts of CONAF, the National Forest Corporation, which manages all Chilean national parks. The first day leads to the western branch of the ‘W’ along Lake Grey, and ends up at the Refugio Grey, facing the fabulous Glacier Grey. This retreating glacier is one of large glacial tongues flowing down the Southern Patagonian ice field. Blocks of ice constantly collapse from this impressive glacier into the greycoloured lake, and the resulting icebergs are pushed away by the ferocious Patagonian winds and punctuate the surface of the lake.

The second day of the hike brought us to the gate of the Vallé Francés, the central branch of the ‘W’. The track follows the shore of the deep blue Lake Pehoé, at the very foot of the Cerro Paine Grande. From the campground ‘Campo Italiano’, the view of the laccolith is stunning. An almost 1 km-high white granitic cliff dominates the campground, and the contacts with the dark sedimentary host rock are spectacular.

The track of the third day follows the shores of the astonishingly turquoise Lake Nordenskjöld. The extreme winds often lift up misty spray from the wavy surface of the waters. On the southern shore of the lake, a beautiful syncline smiles to the trekkers; whether it encourages them or makes fun of them depends on their physical condition! The hiking day ends along the eastern branch of the ‘W’, either at the Refugio Chileno or higher in Campo Torres.

The fourth day starts in the early morning darkness, to access the foot of the Towers at dawn. If you are lucky enough to wake to clear skies, the early rising sun lights up the towers, creating an unforgettable scene of the three gigantic natural cathedrals glowing red in the sunlight.

A Dream Destination?

‘In southern Patagonia, there are no poisonous snakes, spiders, or dangerous predators… but there is wind!’ This is an excellent summary provided by the owner of the Erratic Rock hostel at Puerto Natales. For the locals, a 100-km/h wind is just a standard breeze, so the winds can make trekking quite an adventure. Imagine an engine roaring nearby for a whole day: this is what we experienced for days in this part of the world. Several times during our trek, the ferocious Patagonian winds pushed us over. On our last morning, a sudden gust blew our breakfast all over the surrounding countryside!

Obviously, such conditions discourage the practice of unconventional outdoor activities. At Refugio Grey, we met a self-called ‘professional air-diver’, or base-jumper, who was researching the possibility of base-jumping the Paine’s Towers. When we asked about the result of his investigations, he instantaneously concluded: ‘Are you crazy? I don’t want to die!’

Obviously, the winds had a considerable impact on our cycling too: if the head wind did not kick us out of the road, we sometime managed to cycle at 4 km/h on a perfectly flat, tarred road! But conversely, we had to brake when tail winds pushed the bikes to 50 km/h; and incredibly we climbed uphill slopes freewheeling at 15 km/h.

Importantly, the Patagonian winds considerably enhance fire hazards. The Torres del Paine National Park unfortunately experienced several dramatic fires in 1985, 2005 and 2011–12 induced by careless tourists. The 2011–12 fire destroyed about 176 km2 of the reserve, including 36 km2 of native forest, and the park was closed for over a month. The economic consequences for the region were enormous. These dramatic events show that the protection of such a wonderful geological marvel is a collective responsibility.

Acknowledgments

The Andean Geotrail project was endorsed by the International Year of Planet Earth. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Guilde Européenne du Raid, the Conseil Régional Rhônes Alpes, the Conseil Municipal de Bourg-en-Bresse, the French Ministère de la Jeunesse et des Sports, and material support from Decathlon and Physics of Geological Processes.

Further Reading

Altenberger, U., Oberhänsli, R., Putlitz, B., Wemmer, K., 2003. Tectonic controls and Cenozoic magmatism at the Torres del Paine, southern Andes (Chile, 51°10’S). Revista Geológica de Chile 30, 65-81.

Baumgartner, L.P., Michel, J., Putlitz, B., Leuthold, J., Müntener, O., Robyr, M., Darbellay, B., 2007. Field guide to the Torres del Paine Igneous Complex and its contact aureole, Field Guide Book GEOSUR, Santiago de Chile, 185 p.

Michel, J., Baumgartner, L., Putlitz, B., Schaltegger, U., Ovtcharova, M., 2008. Incremental growth of the Patagonian Torres del Paine laccolith over 90 k.y. Geology 36, 459-462, 10.1130/g24546a.1.

Sassier, C., Galland, O., Mair, K., 2011. To Capture Student Interest in Geosciences, Plan an Adventure EOS – Transactions AGU 92, 1-2.

Wilson, T.J., 1991. Transition from back-arc to foreland basin development in the southernmost Andes: Stratigraphic record from the Ultima Esperanza District, Chile. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 103, 98-111, 10.1130/0016-7606(1991)103<0098:tfbatf>2.3.co;2.