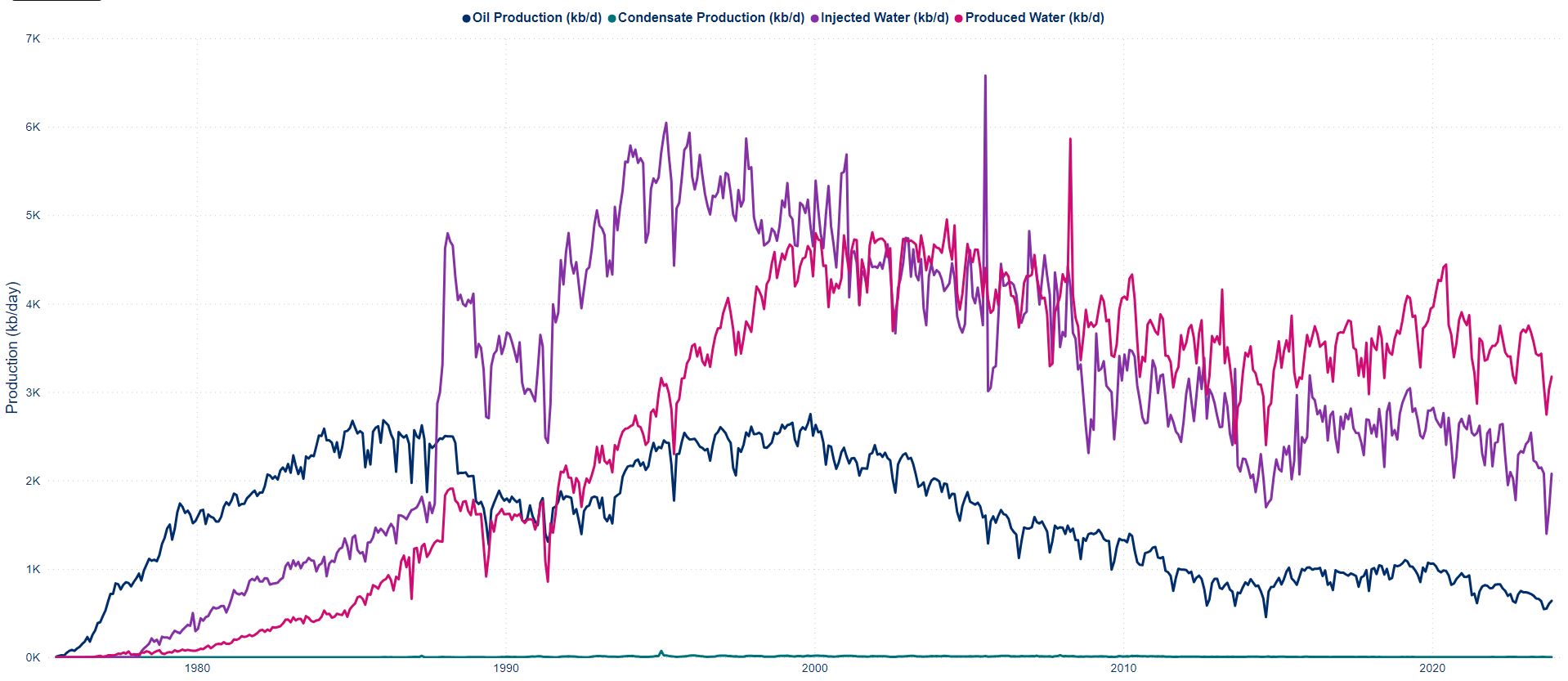

Speaking to an Aberdeen audience about 10 years ago, Jon Gluyas argued that the North Sea oil business was in essence a water industry. Looking at volumes of produced water from many of the late-life fields across the area, he was right. And this is of course still the case. Thus far, using the 70-80⁰C formation waters for something else than re-injection has never happened though. With markets for heat being too far away, the economic case is simply not there. But it highlights an interesting perspective on the oil industry and the potential of its by-products.

Talk about by-products is something that can be observed more often these days, with for instance hydrogen and helium being a close couple in places and geothermal and lithium in others. The major hydrogen seep that was found in an Albanian chrome mine can also be seen as a by-product, as well as Helium One recently suggesting that the brines they found in Tanzania may be used for geothermal purposes. There are even some cases where the initial by-product appears to become the most important target of the operation.

By-products have always been around in subsurface projects. Think about the production of helium from American and Qatari gas fields. But with an increase in exploring for new natural resources, there seems to be an uptick in the number of cases where by-products are suddenly seen as quite important to make the economic case for the project as a whole.

The recent hydrogen exploration drilling campaign near Adelaide is an example of this. The company, Gold Hydrogen, suggested before drilling commenced that in case of success, the entire city of Adelaide could potentially be running on hydrogen from their acreage. As the results came in, even though hydrogen was found, helium as a by-product crept into the press releases. Analysis of the geological data found thin fracture zones that allow hydrogen to seep towards surface, however, the volume and production potential of the actual reservoir they connect to is still questionable. So it is no surprise that the 6.8% helium concentration became a more prominent feature in the reporting. Helium is a much more valuable gas and even small volumes can be economically produced.

The United Downs geothermal project is another example where the focus has diversified. Initially drilled as a doublet to produce electricity from 160⁰C brines from a major fault zone in granitic basement, it turned out that lithium concentrations in the brines are quite high. Now, the project also looks at ways to extract the lithium from the brine. And with the wells producing only up to 2 MWe, there must certainly be an economic driver to capitalise on another ingredient of the produced brine.

Maybe the geothermal water produced in the North Sea can be used after all. The UK government’s net zero targets require the first offshore installations to eliminate their carbon emission by 2030 and harnessing latent geothermal heat could contribute to this.