Oil was first exploited commercially in Romania in 1857 and, since then, the industry has seen cycles of boom and bust, prosperity and decline. One of the main factors in these events was the geographical location of the country, situated on the eastern side of Europe with access to the Black Sea and within the competing orbits of Russia, Turkey and Germany. Romanians have a proud technological and geological record in the oil industry, but international rivalry brought a troubled narrative to the story of their land.

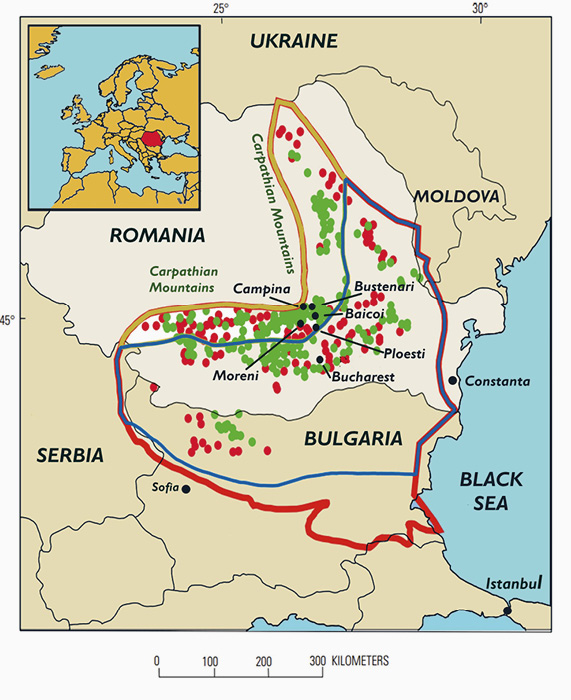

Although the border areas of Romania were considered promising, it was a 45- by 15-mile area on the south side of the Carpathian Mountains in the vicinity of Ploesti that became the main producing area. The oldest oil fields of Campina and Bustenari were discovered close to the mountains on thrust-faulted anticlines, while other larger fields such as Moreni and Baicoi were found on anticlines with exposed salt cores. These discoveries brought geologists from across Europe who carried out stratigraphic and structural studies of the country, as well as attracting the interest of oil companies of the wider world. Illuminated by oil lamps, the capital Bucharest was known as the ‘Paris of the East’.

In 1895 a mining law allowing the investment of foreign capital was passed, leading to an influx of companies from abroad. The Bank of Hungary founded Steaua Romana, which was to become a mainstay of the industry. The following year Standard Oil of New Jersey (Jersey Standard) formed Romano Americana and bought leases in the Moreni field. In 1903 Deutsche Bank representing German interests reorganised Steaua Romana after it went bankrupt. In 1905 British, French, Belgian and Romanian firms were involved in the industry, followed by Royal Dutch Shell, which created Astra Romano in 1908 and took over the larger Regatul Roman. Two years later, this company was the leading producer in the country, accounting for some 3.8 million barrels of oil.

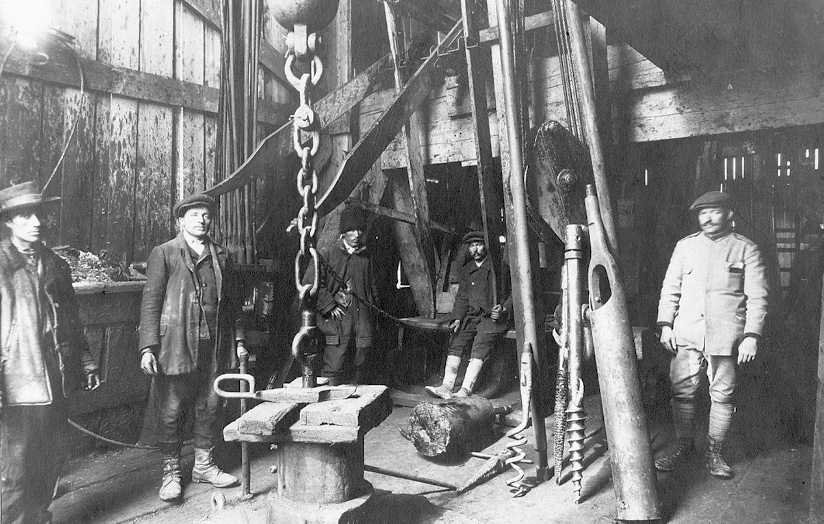

The pre-WWI oil industry was in many ways a showpiece of technology and geology, counting the invention of the blow-out preventer among its achievements. However, Romania was a rural economy and the principles of agrarian land distribution held sway, with ownership in many oil-rich districts divided between small strips of land. By 1905, a team led by Professor Ludovic Mrazec of Bucharest University, the first Romanian geologist to support the organic origin of petroleum, had mapped the country and identified suitable sites for testing; but there were many land speculators asking for inflated prices and, when British geologist Arthur Beeby-Thompson visited Romania, he found that many oil wells were still being dug by hand.

Nevertheless, the country was a rising star in the petroleum world. By 1915, the industry was in the hands of 94 companies, with foreign interests owning about 95 per cent of production. But when Romania declared on the side of the Allies in 1916, the British requested the government to destroy its oil installations in order to deny them to the advancing Germans and more than 1,500 wells were plugged and 70 refineries destroyed. ‘The Romanians, under English orders and directions, had effected a very thorough destruction of the oilfields’, observed German general Erich Ludendorff. Oil production dropped by three quarters, although geologists from Steaua Romano were able to assist in restoring some output to the oil fields.

After the Germans withdrew in 1918, the wells and refineries were repaired, but a sluggish recovery in Europe meant that demand for Romanian oil was low and another six years would pass before production regained its pre-war levels.

Nevertheless, the country’s reputation endured: in 1920, it was observed in a British government report that ‘Romanian methods of winning oil are at the present time second to none.’

Great Power Rivalry (1920–1939)

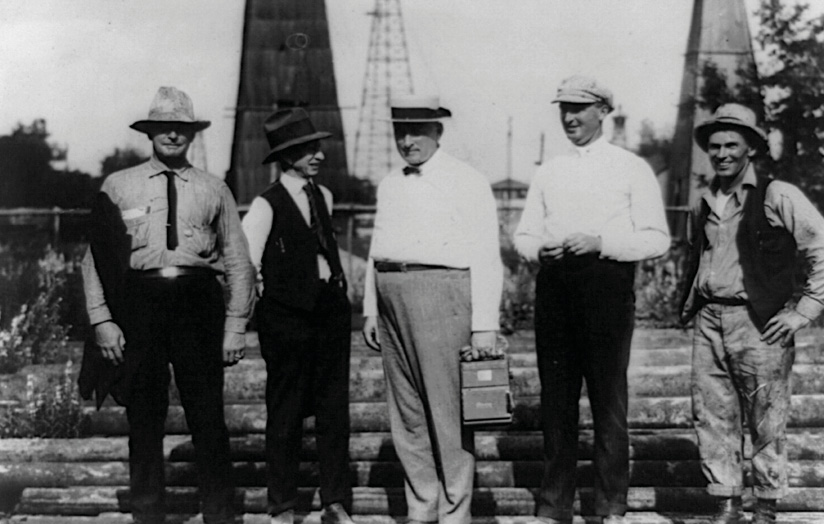

‘Imagine hundreds of gigantic oil derricks, black toothpicks as tall as a ten-storey building reared up on the plain. Back of them picture mighty mountains cutting the sky, and in front the grain-laden lowlands through which the Danube is flowing to the sea’, American writer Frank Carpenter wrote of the Moreni-Tuicani oil field in 1923. Apparently Dr Nerasic, head of the Geological Institute, had predicted there was so little chance of finding oil at Moreni that he would drink every quart of it. No doubt, like Dr G.M. Lees who promised to drink every drop of oil found in Bahrain, Nerasic rued his words. Romania ranked sixth among the oil producers of the world, and Jersey Standard had invested over $20 million there.

This was a critical time. The government was attempting to address the foreign domination of its oil industry by nationalising the mining subsoil, although ‘gained rights’ were protected. The new law brought new problems such as competitive drilling on small tracts, speculators and petty bureaucracy, but engineering methods improved and production increased. Another mining law in 1929 restored the rights of foreign investors by putting them on an equal footing with Romanians.

External factors buffeted the industry: the world was suffering a glut of oil with new supplies, especially cheap oil from Russia. Attempts by the oil barons of the West to control oil prices failed, and the Wall Street Crash left those companies with weak finances struggling to avoid bankruptcy. A massive well fire in the Moreni field, the so-called ‘Torch of Moreni’, burned for over two years before it was extinguished by the American firefighter, Myron Kinley. And yet, despite these troubles, Romanian oil production continued to grow.

At the heart of foreign interest in Romania was a realisation that oil was crucial to future military success. The spectacle of French soldiers in WWI being transported to the front line in Parisian taxis after their railway system had failed was not forgotten; but American oil was susceptible to attack from German submarines, and the French needed a reliable source of oil closer to home.

Romania was the obvious choice, with transport routes available through the Danube, Black Sea and Mediterranean. Having gained a share of the forfeited German oil holdings as the spoils of war, the French oil industry grew and prospered. Together with their British and Romanian partners, they helped to put Steaua Romana back on its feet. It was a valuable training ground for future executives of Compagnie Française des Pétroles (the forerunner of Total), and for their subsequent dealings in the oil business. Several French managers learnt their trade in production, refining, marine shipping and marketing in the oil fields of Romania.

Having also relied on American oil supplies during World War I, Great Britain focused on developing its petroleum interests in far-flung lands, notably Iraq and Iran, and showed little diplomatic interest in Romania, although British capital and technical expertise were still involved there. However, the French, despite their early interest, failed to capitalise on their position, and a slide into the German orbit seemed inevitable, particularly when France fell to Germany in June 1940.

World War II (1939–1945)

Since Germany’s crude oil reserves were meagre, waxy and unsuitable for motor and aircraft fuel, it relied on home-made synthetic oil and imports from Romania and Russia to make up the shortfall. The militarisation of Nazi Germany brought a powerful spotlight onto Romanian oil, for German control of the Romanian fields was vital for success in the coming war, especially if supplies from Russia ceased. And so Germany became Romania’s most important trading partner, accounting for almost 40 per cent of its exports in 1938.

At the start of the war, Romania reached an agreement to allow Germany access to its economic resources but remained neutral. There was a strange sense of being out of the war but also a part of it: British and French diplomats carried on their business in Bucharest as Swastika-flying barges plied the River Danube with cargoes of oil for the German war effort. Behind the scenes, the British planned an ambitious scheme to fly 400 troops on Bristol Bombay aircraft from the Middle East and land them in the Ploesti area to sabotage the oil fields, but the idea was, perhaps fortunately, abandoned.

As Allied relations with Romania deteriorated, foreign employees were expelled from the oil fields, which fell increasingly under German control. Romania took the last, fateful steps to war in September 1940 when a right-wing coup brought Fascist prime minster Ion Antonescu to power and Germany invaded the country a month later. Ominously, a massive earthquake damaged the oil refineries at Campina and the pipelines between Ploesti and Constanta, although a German technical commission quickly effected repairs. In June 1941 Romania took part in Hitler’s invasion of Russia but, when the offensive fell short of the Baku oil fields, Germany’s dependence on Romanian oil was sealed.

The point was not lost on the Allies. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed a joint bombing strategy to destroy the Romanian oil fields ‘by air bombardment’. At the beginning of August, ‘Operation Tidal Wave’ saw 178 B-24 Liberator bombers attack Ploesti, but the results were disappointing. Fifty-four aircraft were lost and only limited damage was inflicted on the oil installations, which soon resumed production. Despite follow-up raids, the Allies never managed to choke off oil supplies to Germany. That would take a monarchist coup d’état and Romania switching sides in August 1944.

After the war, the industry fell on hard times. The Russians seized much of Romania’s petroleum equipment as war reparations. Foreign companies returned in 1945 to a country with a communist regime, which nationalised the industry in 1948; the managing director of Romana Americano was imprisoned and the general manager fled the country.

To the Present Day

For the next ten years, the Romanian oil industry was geared towards the needs of the Soviet Union. Although a new enterprise, Sovrompetrol, was set up as a joint Soviet–Romanian venture to control the industry, the bulk of oil production was diverted to Russia. It was only with the death of Stalin and the advent of Khrushchev’s policy of de-Stalinisation that full control of the oil industry was returned to the Romanian government. Released from the petty bureaucracy of the pre-war years, the industry saw a revival of exploration and the discovery of new fields. Oil production peaked at 15 million tons in 1976, and the first exploration well in the Black Sea was drilled, but output thereafter went into decline. The revolution of 1989 brought an end to communist rule and a move towards a free-market economy.

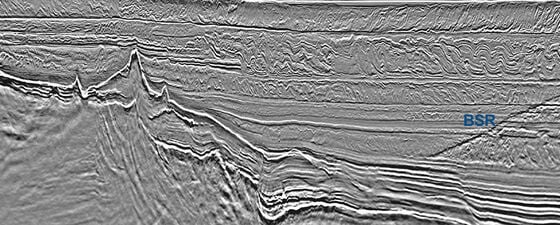

Today, Romania’s oil policies reflect the lessons of the past by seeking energy independence. The country is the third-largest oil producer and has the fourth-largest crude oil reserves in Europe with 600 MMbbl of proven reserves as of January 1, 2014. It has nine refineries with a total capacity of 467,642 bopd, giving it among the largest refining capacities, although oil production has continued to decline, with total production of crude oil and other liquids dropping from 134,000 bopd in 2003 to 104,000 bopd a decade later. Meanwhile exploration continues with 3D seismic acquisition revealing prospectivity in structurally complex areas, such as the Carpathian Bend Zone, and recent gas discoveries in the deep waters of the Black Sea are highly promising.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to PeterMorton for his kind assistance.