“ I recently gave a talk in Kuala Lumpur,” says geologist and pore pressure specialist Karol Jewuła, “for which I made an overview of drilling-related issues with wells drilled from 2014 to 2021. What turned out to be the case? Most problems are still related to pore pressure and geomechanical issues. To me, it illustrates that despite all the technology we have these days, we are still unable to mitigate all risks pre-drill. The Earth is a pretty nasty partner to work with, and that’s why we need to monitor things closely when drilling.”

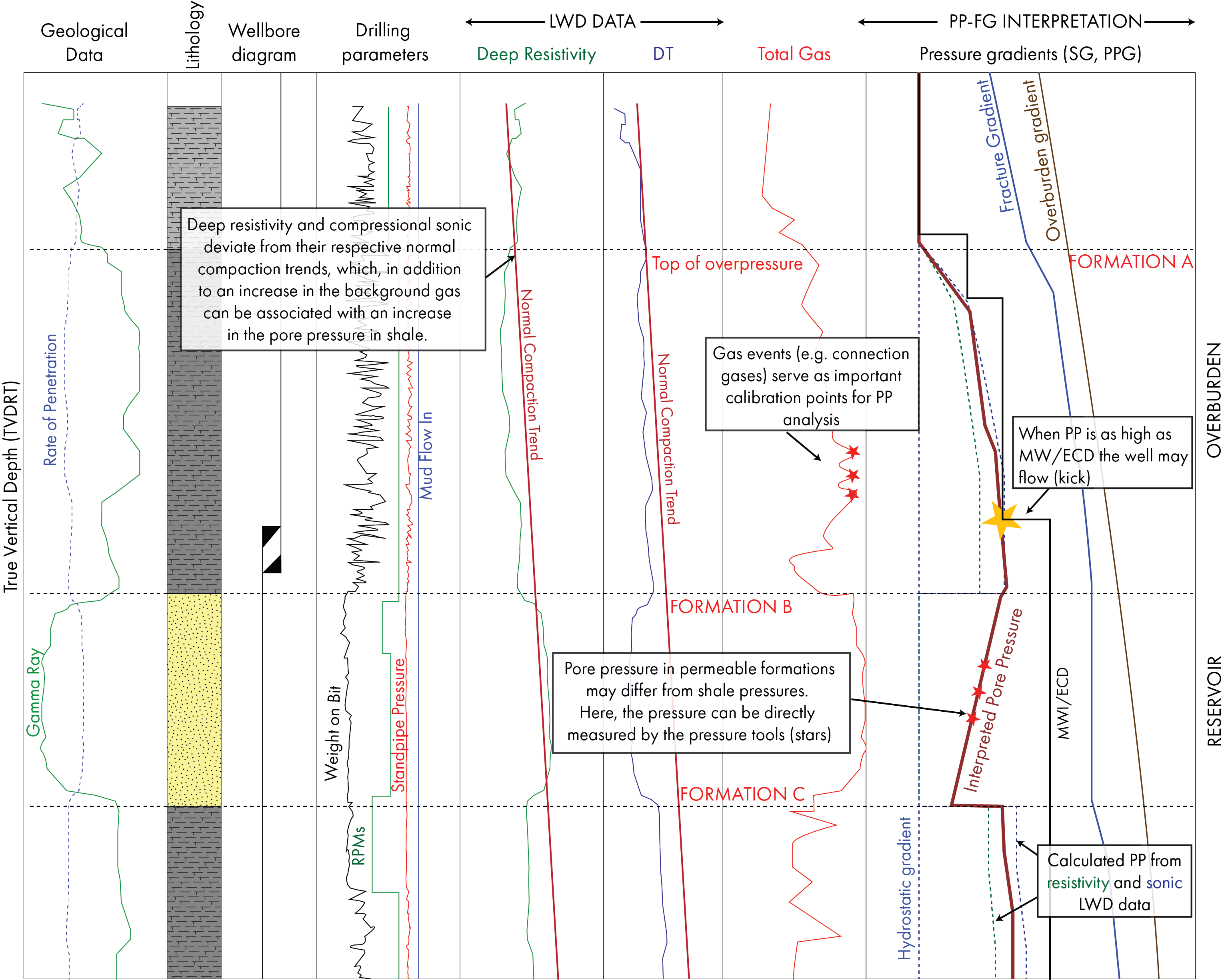

“The basic thing we try to do as real-time pore pressure and geomechanics engineers is to minimise uncertainty when it comes to staying in a safe drilling window,” says Karol. “We use all the parameters we’ve got to see if there are indications that mud weight is too low, leading to formation collapse and possibly an influx of formation fluids, or mud weight being too high, which means that we can frac the formation and experience mud losses.”

But, at the end of the day, it’s easier to control kicks than losses. “That’s why it is very important to stay away from the fracture pressure, maybe even more so than staying away from the formation pressure,” explains Karol. “The complicating factor here is that there is not always agreement on the definition of the fracture gradient, with each company using their own or even multiple scenarios. That’s why we often define the minimum fracture pressure of the ones that have been calculated, to stay on the safe side.”

Frontier wells

Karol and his colleagues Łukasz Karda and Tim Sheehy at Bizon are mostly called in for frontier exploration wells, where there is not enough offset data to develop a sound understanding of the expected pressure regimes.

“We can make a nice pre-drill well design with casing points, but in my experience, nature always throws a curve-ball and we are the ones who are tasked with picking that up and communicating that,” says Karol. As an example, he recalls a recent project in South America where everyone thought pre-drill that pressure would be quite low, but as soon as operations started, pressures were significantly higher than expected.

“The most important parameter we use as we continuously monitor drilling is gas data,” says Karol. “This is the most crucial set of data. And not only total gas but also its composition. This can tell us more about whether it is connection gas we are dealing with, or whether there is more to it.”

“As soon as we start a job, we try not to look at the predicted gradients all the time, as that leads to anchoring and a tendency to confirm the predictions made by our client. It is the data we acquire during drilling that should be leading and if necessary, we need to revise the pre-drill model, even if the client may not be too happy with that.”

Not something new

Real-time monitoring is not just something of the recent past. Back in the 1970s, even though LWD did not exist yet, inferences on pressure regimes were made real-time using drilling data. For instance, when drilling rates increase significantly, this is often a sign of reducing overbalance. Without having access to any other type of information, it was always known that higher formation pressures could be behind this.

“A lot has changed in the way we handle our data, the ease with which we can now work from home, and the much wider range we’ve got available. But at the same time,” says Karol, “we still have to rely on the basics to do the job properly.”

Drillers want just a number

“Communication is the most important aspect of our job,” says Karol. “It is our routine to report to the operations geologist and drilling superintendent, and not to the rig straight away. Ultimately, the power sits in town and that’s where our information is required first.”

“I do adapt my style of reporting to the people I report to, with very short reports to the drilling engineers who are not interested in a scientific justification of my decision. The more elaborate reports are for the geology nerds like me,” he jokes.

Communication is the most important aspect of our job…

Karol is now used to do his job from home. “I have worked on the rig, I have worked in the client office, but these days I do really prefer to work from home, because it feels more independent. And that is exactly what our role should be. We have to be independent and let the incoming data inform us about any potential intervention. There is no real advantage to being on the rig nowadays, apart from the possibility to examine and evaluate cavings personally versus looking at pictures.”

And then, at the end of some of our jobs, when the well is drilled successfully, Karol is sometimes questioned by the drillers: ” Why were you needed? We haven’t experienced any issues.” “That is precisely why we were there!”

Going deeper

Karol is excited to see how wells are being drilled deeper and deeper these days. “Managed Pressure Drilling (MPD) has been an instrumental technology in that sense,” he says, “because it allows us to drill through very narrow pressure windows and control mud weight at surface directly through pressuring up the return mud line. This results in a much more instant response, and I believe that without this technology some of the deeper targets these days could not have been drilled.”

Is real-time monitoring still required in that case? “Yes, I’d surely say so,” says Karol, “because you can better define the limits of the system and make a more informed decision as to how far you can go.”

GOING INDEPENDENT

Karol started working for IKON Science in 2014, where he learned the ropes of pore pressure prediction from people such as Eamonn Doyle, who gained decades of experience monitoring wells in the Norwegian sector. “He was the best teacher I’ve ever had,” he says.

But the oil crisis and the big wave of redundancies led Karol and his business partners to become consultants soon after. However, it was the busiest time he and his colleagues ever had, mainly because wells committed to during the good times were still being drilled in the first few years of the downturn. This enabled him to work on many wells all over the world, from Brunei, Suriname and West Africa, to the Falklands.

“How does the future project pipeline look?”, I ask at the end of our conversation. “I have a bit of a funny feeling about it,” says Karol. “There are quite some factors that put pressure on continued exploration drilling, even when we hear “Drill, baby, drill” all the time. But this mostly applies to development drilling, for which our service is generally not required. It’s the exploration wells we need, and that’s a place where I don’t really see a major uptick at the moment.” But is it reason to be concerned? “No,” Karol concludes, “being independent always comes with ups and downs, and if there is one certainty, it is that the demand for oil is not going to slip away tomorrow.”