Pelotas Basin in Brazil – A fantastic analogue to the Orange Basin in Namibia

The astounding discoveries of gas condensate in South Africa (Brulpadda and Luiperd) and, more recently, of oil and gas in Namibia, drew the attention of the global petroleum industry. Therefore, major oil companies are now turning their sights to the other side of the South Atlantic Ocean, namely to the conjugate margins of southern Brazil, Uruguay, and northern Argentina.

The Greater Pelotas Basin is comprised of a single, uninterrupted, enormous sag basin containing large thicknesses of Lower and Upper Cretaceous to Cenozoic Drift Sequences, resting upon volcanic substratum (either Seaward Dipping Reflectors (SDRs) or Oceanic Crust).

In this context, we are considering only the southern part of the Pelotas Basin, situated south of the Torres High (see map). Ten wells (9 in Brazil, 1 in Uruguay) have been drilled in this frontier area and only three of them in deep/ ultra deep-water.

These discoveries proved the capacity of the source rock system to generate commercial quantities of light oil and gas. The successful petroleum system is named the Cretaceous Marine Anoxic Shales – Upper Cretaceous Turbidites.

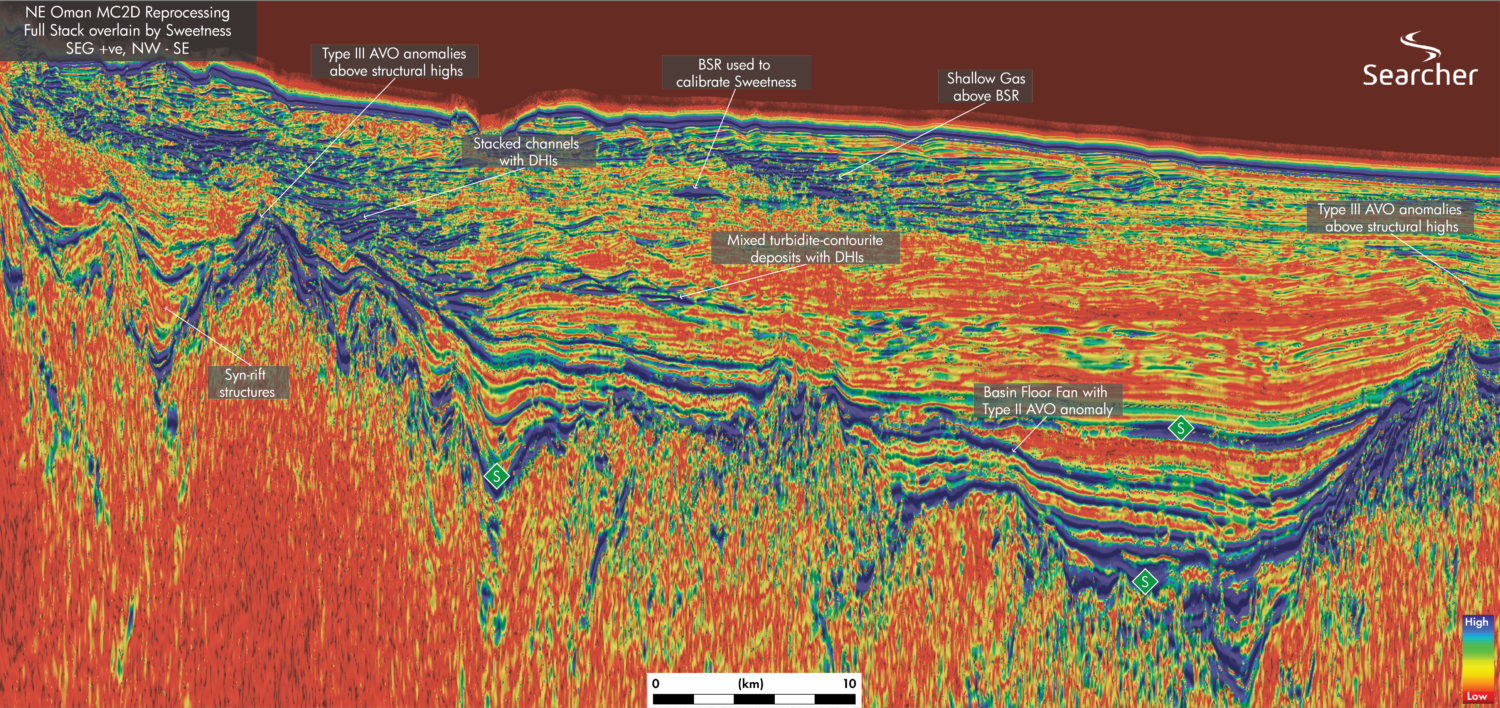

The source rocks are marine anoxic shales of Aptian- Turonian age of which the Aptian shale seems to be the richest and most effective contributor (see seismic lines). The reservoirs are Upper Cretaceous turbidites deposited in large basin floor submarine fans fed by channelized systems. With the reservoirs situated directly on top of the source rocks, the traps are mostly of stratigraphic nature.

In three of the four discoveries cited above, the reservoirs are of Aptian age and rest upon the Aptian shales. This system is ubiquitous in the continental margins of the South Atlantic Ocean. It has unveiled large reserves and production potential in Guyana and Suriname, Ghana and Ivory Coast, Sergipe-Alagoas, Equatorial Guinea, Espirito Santo, Campos, Santos, Angola, Namibia and South Africa. The only variation among these areas is the age of the main source rock; sometimes it is Aptian, sometimes it is Turonian.

The time has now come to prove the presence and effectiveness of these source rocks in the Greater Pelotas Basin, especially in southern Brazil. All the favourable indicators are present in this conjugate South American margin:

- Seismic facies indicative of a basal package of source rocks;

- Overburden in excess of 3,500 m to allow for the generation of hydrocarbons;

- Direct Source Indicators (DSIs) as Type III/IV AVOs in sub-horizontal, tabular, parallel seismic facies indicative of low energies;

- Seismic facies indicative of turbidite reservoirs in submarine fans, lobes and channels

- Direct Hydrocarbon Indicators (DHIs) such as bright spots with Sweetness anomalies and/or Type III/IV AVOs;

- Direct Migration Indicators (DMIs) such as gas chimneys, flags along faults, buried mud volcanos, shallow pockets of gas;

- Trapping geometries such as updip and lateral pinch outs, draping over buried basement structures and mixed traps.

Striking similarities

The foldout displays the great similarity between 2D seismic lines in the Brazilian Pelotas Basin and in the Orange Basin in Namibia. The SDR economic basement is prevalent in both basins. The basal package of source rocks presents the same seismic facies of tabular, parallel, continuous alternating reflectors with moderately strong negative amplitudes.

The source rock package in Pelotas seems to be thicker and more complete, possibly due to the presence of the Turonian. The total sediment thickness map (see map) shows that the main hydrocarbon kitchen in the Greater Pelotas Basin lies exactly beneath the Brazilian portion of the basin.

The reservoir is magnificently displayed as the Venus submarine fan resting on top of the Aptian source rock; highlighted by a strong bright spot at the far-right end of the Orange Basin line. In Pelotas, several indications of bright spots in channelized and pinch-out seismic facies resting upon and interlayered with the source rock package point to potential accumulations of hydrocarbons.

Regarding sealing in these source/reservoir sections, both basins are covered by identically thick seismic facies indicative of undisturbed low-energy clastic sediments, the monotony of which is frequently broken by mass-transport deposits, channelized facies and wide, laterally pinching-out layers suggestive of stacked submarine lobes/fans.

Turbidite geometries

The dense grid of 2D seismic data in the Pelotas Basin allowed the identification and mapping of several potential mostly Upper Cretaceous prospects. The most important ones are those interlayered with the source rocks, as demonstrated by the Brulpadda, Luiperd and Venus discoveries. All of them were first identified by their turbidite-like geometries with associated bright spots. The confirmation of the anomalously low-velocity character of the bright spots was subsequently highlighted by the Sweetness attribute and DHIs were obtained by the (F-N)*F attribute, separating Types III and IV AVOs.