In a major turnaround for a profession that fell out of favour in the 1980s, a number of palynology consultancies are growing rapidly and struggling to meet the demand for skills.

Palynology’s demise in the 1980s coincided with the arrival of electric well logs. Many petroleum geologists believed downhole instruments told them all they needed to know and arcane reports based on microfossil contents of drill cuttings were no longer necessary.

In a decade when cost-cutting reigned, palynologists were routinely among the first to be laid off. But microfossil experts – who are now in critically short supply after decades of underinvestment by the oil and gas industry – are having the last laugh.

Solving Exploration Problems

The revival is being led by a new breed of palynologists such as Perth-based Jeff Goodall, who have a keen focus on applying their science to the problems of petroleum discovery.

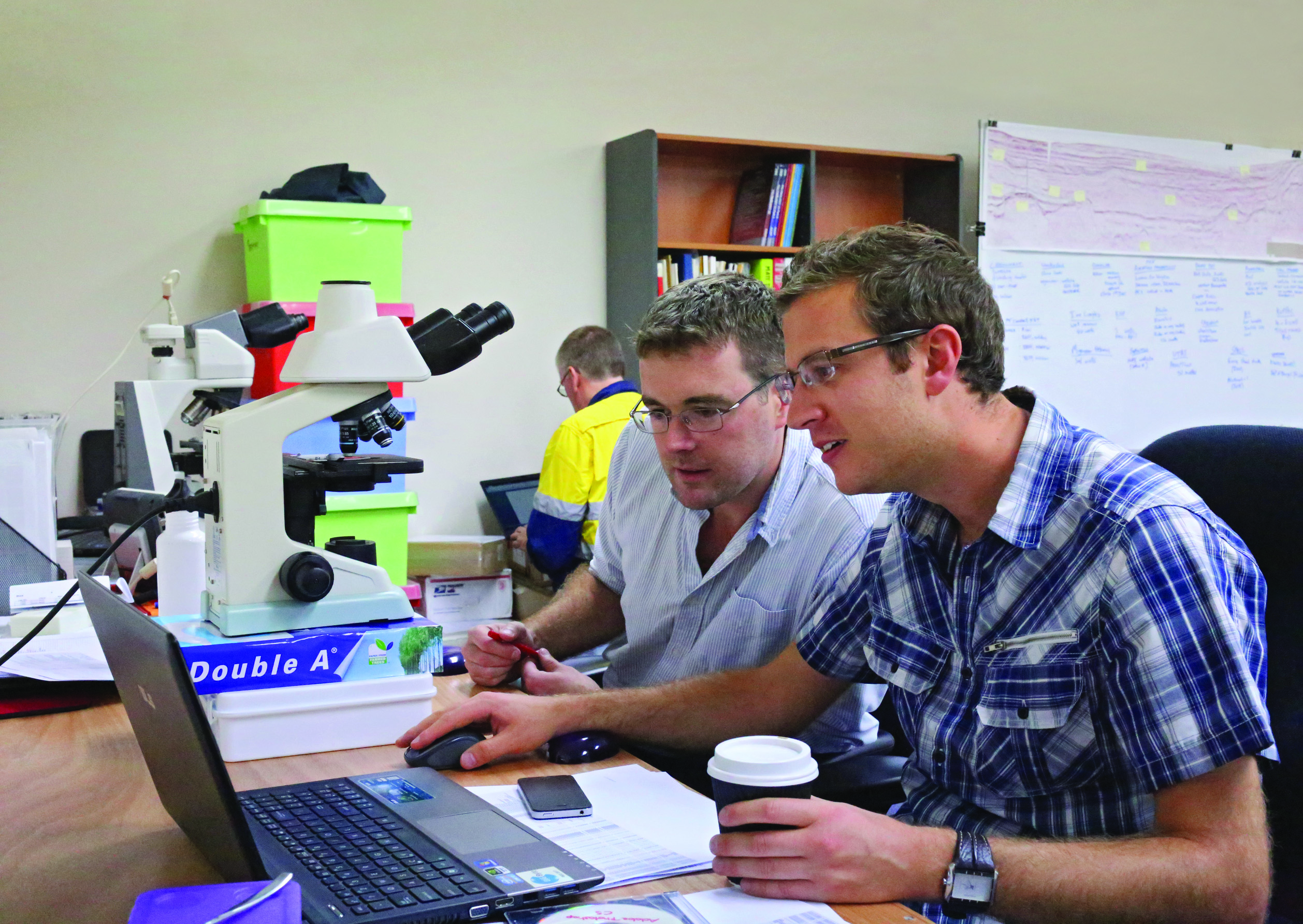

UK born and educated, Goodall migrated to Australia in 1999 to take up an in-house palynologist position with Santos. The Adelaide-based independent had bucked the 1980s shift from palynology and maintained a sizeable department under the leadership of Geoff Wood. Goodall left three years ago to join a consultancy founded some 30 years earlier by an icon of the industry, Roger Morgan, who is now phasing into retirement. The new partnership known as Morgan Goodall Palaeo (MGP) has grown from two palynologists in 2011 to more than a dozen today, servicing Australasia and the South East Asian region. It is within striking distance of laying claim to being the largest consultancy of its kind in the world.

Goodall says the growth of MGP and the revival of palynology more generally is due to a number of factors. “There is growing awareness among petroleum geologists that palynology is much more than age dating. It’s being recognised as a tool that can help them gain a much better understanding and de-risking of the geology, allowing them to go for the more difficult targets, and that’s increasingly important now all the easy oil has been found.” He added that palynology also provided solutions for modern exploration challenges, such as horizontal and directional drilling, especially for unconventional targets.

Goodall said MGP’s rapid growth was due to its emphasis on applying palynology to solving exploration problems, and speaking in a language that geologists understood. “We convert the science of palynology and all the long Latin names into a language the geologist can understand so they can go and find oil. Most people are not interested in Latin names, but if you convert them into geological thought, then that’s a powerful tool.”

Re-writing Geology

He says the working life of the modern palynologist is far removed from the stereotype of a lab-bound technician who is obsessed with the taxonomy of tiny organisms.

“These days, most of us work on the drill site where we are under intense pressure to provide information within an hour or so of drill cuttings reaching the surface,” Goodall explains. “The information we provide is vital to decisions about drilling that could cost or save our clients millions of dollars. Wellsite palynology routinely rewrites perceptions of where the oil or gas is going to be found. There is often a perception among clients that their oil or gas field is contained in a nice blanket of sand. When it comes to drilling, particularly with horizontal wells, the sand can disappear and may or may not re-appear. The palynologist can provide real-time information about whether it’s the same sand, and that’s something that can’t be done by electric logs.

“It’s not uncommon for the geologist to need to rewrite his geological thoughts on the fly as we are drilling. He or she is basically on our backs all the time wanting our information.”

Goodall said MGP was very active in Papua New Guinea – with about eight palynologists on well sites – because of the very complex geology. “In PNG, the rocks can actually become younger the deeper you drill because the whole system has been tipped upside down. You can imagine how that affects people’s perceptions of where the reservoir might be found,” he says.

Steep Learning Curve

Geoff Wood has been part of the palynology group at Santos since 1987 and today heads a team of three young palynologists and two lab technicians. It is the only palynology group inside an Australian-based oil company, although the largest Australian independent, Woodside Petroleum, has a passionate palynologist on staff, Neil Marshall. He has promoted the value of microfossils within Woodside for 20 years and has been a large supporter of the consultants.

Wood said Santos was committed to training and developing its own experts. “The global majors were battling us for the younger, talented individuals, so we thought we would take on the training of our own staff. Our aim has been to give them an understanding of the geology as well as the palynology – that’s the magic mix.

“In order to survive today in the oil industry, you have to have a good understanding of all the aspects of the industry in terms of the geosciences. You have to understand the geological problems and understand the best way you can use the biostratigraphy to solve the problem.”

He said the present team of palynologists all have five or less years experience on the microscope, but what they lack in breadth of experience they make up for in enthusiasm to learn the trade.

“All trained initially as geologists and were chosen for their interest at graduate entry level in tackling the steep learning curve to become a palynologist,” Geoff says. “They also possess the general petroleum geology skills to become an active member of the exploration and development teams which they are assisting. Their goal is to become proficient in a very specialised skill but have the ability to understand the challenges and problems brought to them by their customers in the exploration and development teams.”

Wood said the nature of palynological studies within Santos had changed markedly recently. “In the past decade, our studies have focused on creating insights at a reservoir scale, rather than a regional scale. The regional-level studies were important when we began exploration in areas such as the Cooper Basin and North West Shelf, but now we are focused at a much finer level.

“For example, palynology allows you to look at the connectivity of reservoir sequences. We can tell our geologists whether the intersections from well to well are co-eval, and therefore likely to be connected.”

Future is Bright

Wood is also committed to teaching his craft at an industry level in Australia. He is Australia’s only palynology lecturer, at the Adelaide-based Australian School of Petroleum.

“Courtesy of Santos, I have given a short course on Applied Biostratigraphy for the honours and post-grad geoscientists each year for the past 25 years. With the major extinction apparently of palaeontology and stratigraphy lecturers in universities worldwide, this course is becoming increasingly important. The students at ASP come from all over the world and I sometimes do a straw-poll of their previous studies in biostratigraphy. Some of the overseas students have exposure to it, but in general palynology seems to have dropped off the radar.”

However, Wood believes the future of palynology is bright. “It only takes a few people within an organisation to work out how valuable it is and it can really snowball. The recent growth of Morgan Goodall and other consultancies is testament to that.”

The revival of palynology is also being actively promoted by Clinton Foster, the chief scientist at Geoscience Australia, who began his career as a palynologist in 1976. In welcoming this renaissance, including the successful employment of new palynologists by Santos and MGP, Dr Foster said there remains a need for people who can teach the subject.

“I strongly supported the push by academia for a new teaching position, and am delighted that industry has recognised the need by generously establishing a professorial position at an Australian university (details are to be announced soon). The re-establishment of palynology as a university subject will ensure the essential taxonomic studies that underpin the science are carried out. We have to get some young bright minds focused on this and I believe we will see the whole science thriving again.”

Foster said Australia had provided some of the world’s greatest palynologists, who had laid important foundations for Australia’s modern petroleum industry.

“Isabel Cookson’s early work was outstanding, and so was Basil Balme’s. He did most of the work for WAPET as they worked out what has happening in Western Australia back in the 1960s. Basil started his career in the 1950s describing spores and pollen from Permian coals in New South Wales, and that work still underpins correlation studies for coal bed methane. More recently, Robin Helby’s detailed and carefully documented work on the North West Shelf, together with studies of Alan Partridge and Roger Morgan, formed the first comprehensive industry standard for the Australian Mesozoic, published in 1987.”

How Palynology Adds Value

Palynologists can tell the wellsite geologist the position of a drill bit within a rock unit to an accuracy of between five and ten metres, according to MGP’s Jeff Goodall.

“The palynologist provides a means of checking the progress of the drill bit relative to the interpreted geology. More than that, we can give the well site geologist an accurate prediction of how many metres the bit is located above a seal/reservoir contact. This can be very important with shale gas targets, which are often highly pressured. We can tell the client when to stop drilling and to start running casing ahead of the contact between the shale and the overlying rocks.”

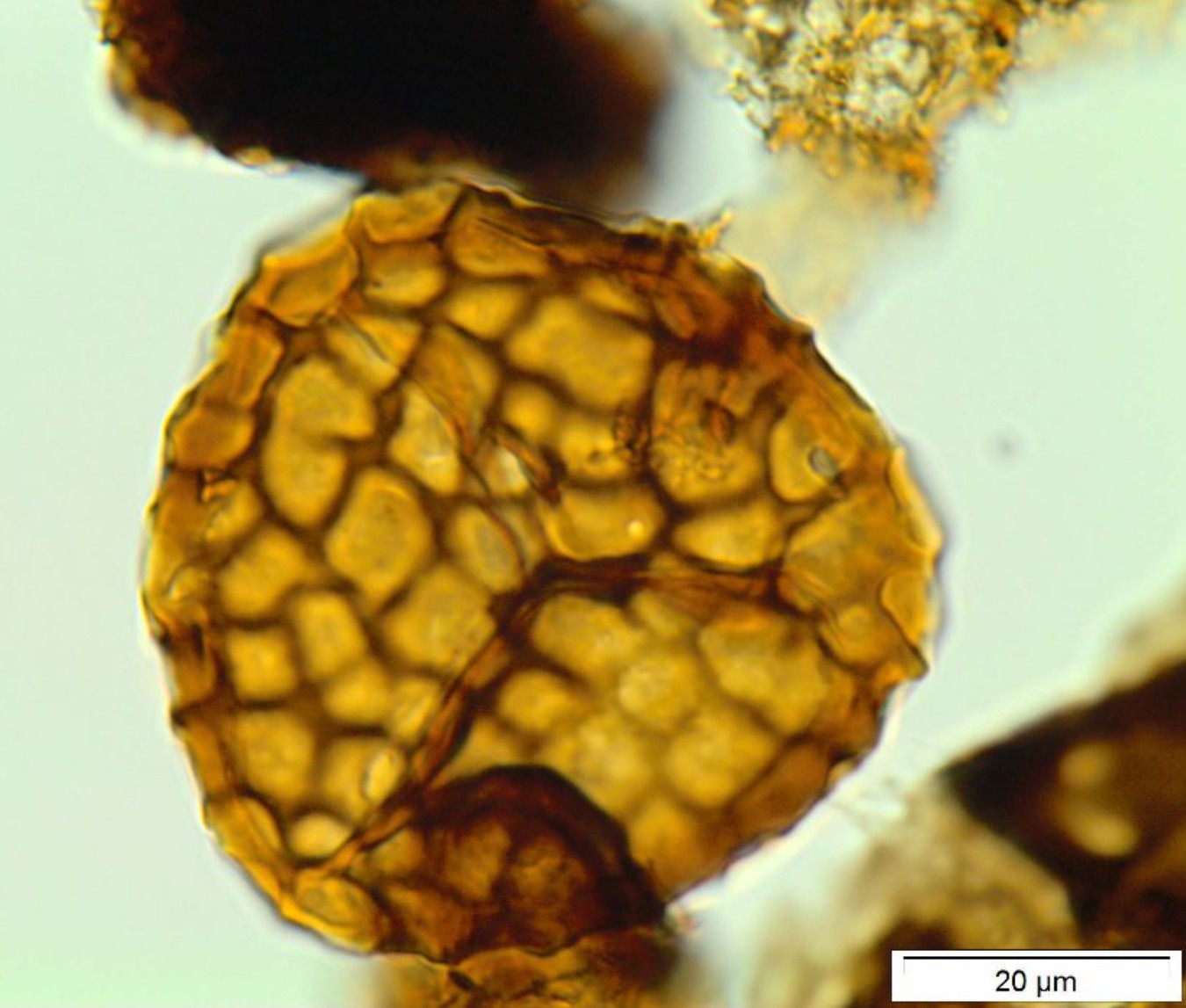

This remarkable predictive power comes entirely from monitoring changes in the microfossils, which include plant spores, pollen, algal remains from land areas and plankton from marine environments. Microfossils can be shaken out of the cuttings or cores by using hydrofluoric acid to dissolve silicates and carbonates, and then studied under a microscope.

Microfossils are key to understanding the evolution of life on earth, as well as the organic matter on which the world’s petroleum industry relies. They reveal a vast amount of information because the intricate shapes of microfossils are restricted to different time periods, allowing a date to be attached to the rock sample. The most important tools of the trade are highly detailed taxonomies of organisms, compiled over more than a century of study. Studying the assemblage of different microfossils makes it possible to reconstruct the climatic and depositional environment.

The type of microfossils can also indicate the likely hydrocarbon products. For example, a rock packed with algal remains is much more likely to produce oil than gas.

Even the colour of microfossils contains vital information. Microfossils are initially clear, but will darken towards black with higher temperatures. This can immediately show whether a source rock has been taken past the oil window into gas generation.