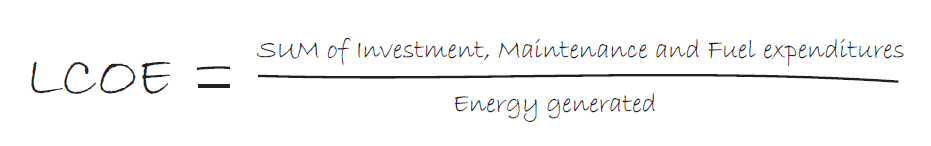

“Levelized cost of energy” (LCOE) measures an energy source’s lifetime costs divided by energy output and is a metric often used for comparing the competitiveness of different energy forms to be considered profitable. The parameter can be a useful tool, but only to a limited extent as it has several flaws, and in its origin was never intended for comparison between different generation technologies.

Among other things, LCOE does not take into account the timing of when the electricity is delivered, or whether the electricity also comes with additional benefits that the power grid is dependent upon for reliable and secure operation. Thus, costs for natural gas and / or battery backup power for intermittent solar or wind farm projects are not considered, or the cost of expanding power grids to other regions with different weather patterns.

As mentioned in my first column in Issue 3, modern societies are completely dependent on a functioning system of reliable energy production. This is essential for an overall assessment of value.

Nuclear plants boast capacity factors of 93 %, on average, versus just 57 % for natural gas and 40 % for coal, i.e. they can operate almost year-round at full capacity. Intermittent sources like wind and solar have capacity factors of 35 % and 25 % (EU based), respectively.

Again full disclosure, I am not a nuclear industry veteran, but I am perplexed that many people, geoscientists included, do not appreciate the full value proposition of nuclear. Particularly when we think about moving to a resilient decarbonized grid and using land efficiently. The things that seem inherent in the definition of nuclear power are not compared effectively and valued by the LCOE metric.

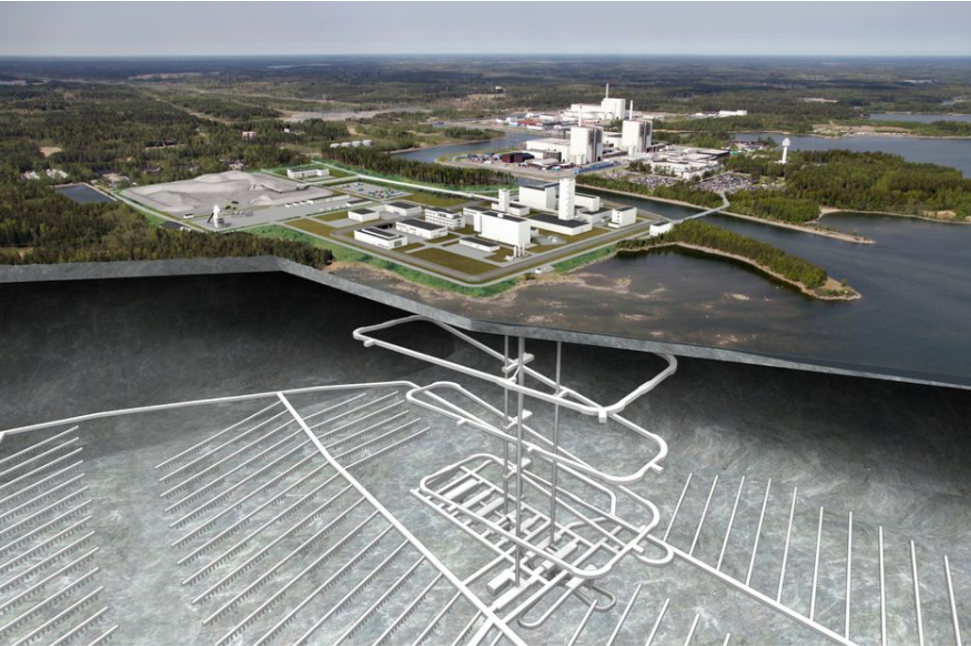

Critics of nuclear power from Norway to Australia cite examples of high costs and construction overruns as some of the main reasons for choosing to build other energy technologies. Initial capital costs for nuclear are high, but given the energy payback, as measured by the net energy (energy supplied per quantity of energy used) nuclear is in a league of its own. Now, there are obviously no bad ideas when it comes to energy generation and we are going to need all forms in much larger quantities than currently forecast, but the core of a successful sustainable energy system going forward should be high net energy reliable baseload sources complemented by intermittent forms in modern renewables.

To bring attention to the LCOE calculation is important for two reasons. First, users of the metric when framing energy trade-offs should understand its simplifications and its intended use. Secondly, and even more importantly, it is to alert us to the limitations of this measure for capturing everything that matters, and why decisions must be made with the entire footprint of the material supply chain, land use, existing network capacity and job creation in mind. Otherwise, we are doing ourselves a disservice.