A common theme emerging during the Devex Conference this week is how reservoirs are more connected than many have initially thought. And this does not always have a natural cause. Below are a few examples presented by various operators over the course of two days of conferencing.

Small scale injectites in Quad 9

High water cut early in the production life of a field, it is not the ultimate operator’s dream. However, it did happen in some of the Quad 9 injectite fields in the Northern North Sea. Leon Barens from TotalEnergies showed that thanks to diffraction imaging of the complex sandbody architecture in the area, the presence of small injectite bodies could be made more visible. Subsequent dynamic reservoir modelling, with the inclusion of the thin thief zones connecting different sandbodies, resulted in a much better match with the production profiles. This explained the rapid water ingress into the wellbores and clearly supported the hypothesis that the system is much better connected that previously foreseen.

A connection between Varadero and Burgman?

A second example of reservoirs potentially more connected than expected was presented by Andrew Miles from Harbour Energy. He showed that a development well in the southern part of Varadero in the Catcher area was drilled recently, anticipating to tap into an undrained compartment. However, the well found water instead, which was subsequently confirmed by the 4D seismic survey acquired last year. This obviously sparked the question how this part of the field could have been drained. Even though many uncertainties remain, one of the hypotheses the team put forward is that this part of Varadero could somehow be connected to Burgman.

Permeable sands and permeable shales

Ted Smith from Harbour Energy gave another interesting example illustrating that the binary view of permeable sandstones and impermeable mudstones is outdated. Using a reservoir modelling approach of a thin Paleocene sandstone reservoir in the Joanne area, he showed that the only way reservoir pressures could have built up again following cessation of production, was the influx of water from the mudstones and siltstones in which the thin reservoir is embedded. Even though permeabilities are much lower in mudstones, values of 100 nanoDarcy are sufficient to ensure water influx into the depleted reservoir over time.

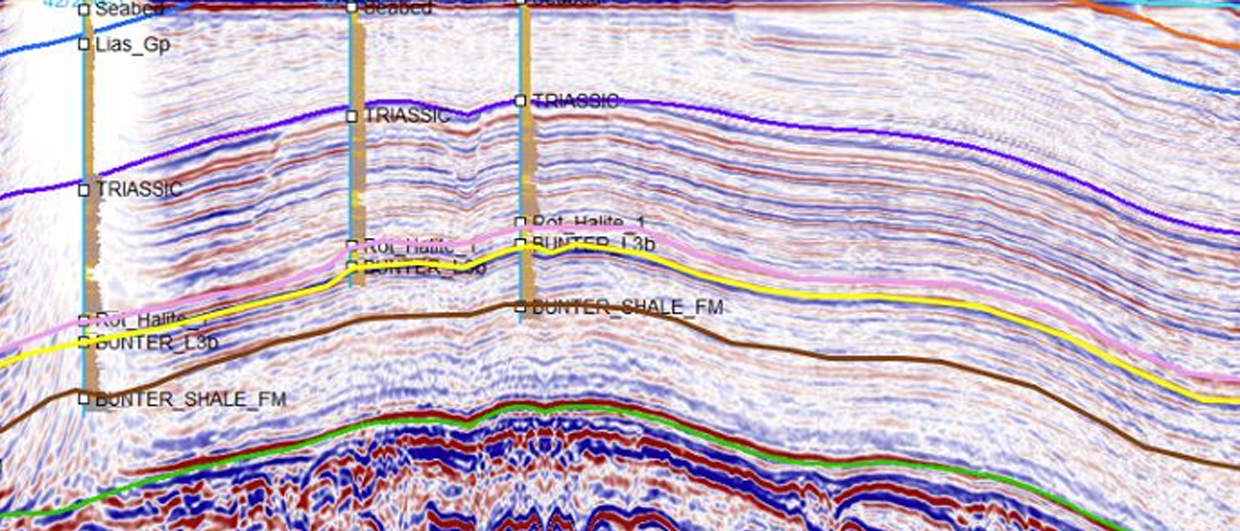

A poor cement job

Last but not least, a final example of the North Sea plumbing system was presented by Matthew MacGregor from TotalEnergies. He gave the first technical overview of the dynamic behaviour of the Culzean field in the Central North Sea following start of production in 2019. The field produces from the Triassic Joanne sandstone as well as the overlying Pentland Formation. Prior to field start-up, the expectation was that both reservoir units were isolated by the Jonathan mudstone, which was supported by differences in fluid composition.

However, even before production from the Pentland had started, the operator already observed a 3 bar pressure drop in the reservoir. This increased significantly after more Joanne wells came online. Rather than a geological explanation to explain the connection between the reservoirs, the most likely scenario put forward now is that one of the early wells (22/25a-9z, see cross-section above) on the field is causing the reservoirs to connect through a poor cement job.

All in all, the above examples nicely demonstrate that the subsurface is more complex than we often anticipate it to be, and that any intervention may also lead to even more pathways for fluids to migrate.

HENK KOMBRINK