It is always good to speak to people at conferences and hear what is going on. That is how I learned about a CO2 storage project that took place in Japan a few years ago, named the Tomakomai Demonstration Project. Within the framework of this project, which ran for more than 3.5 years, the injection of 300,000 tonnes of CO2 took place into subsurface reservoirs.

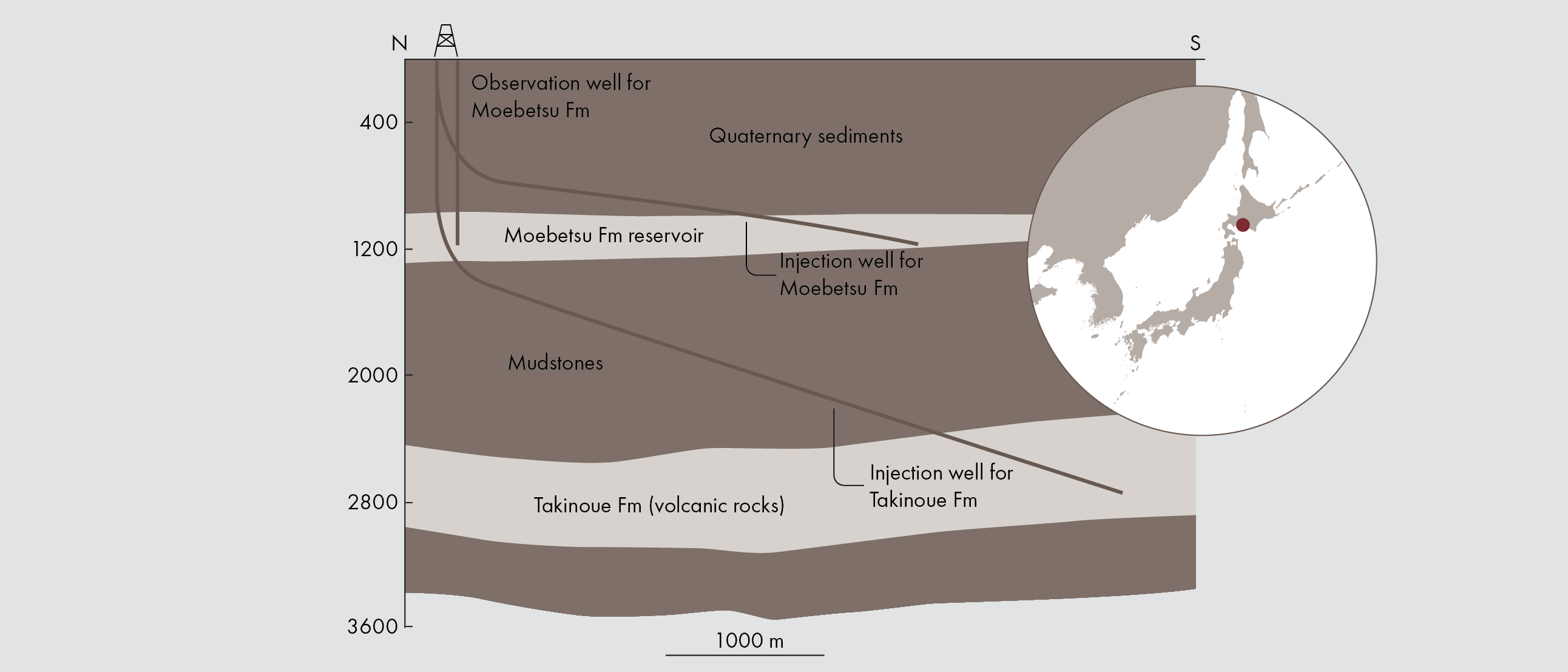

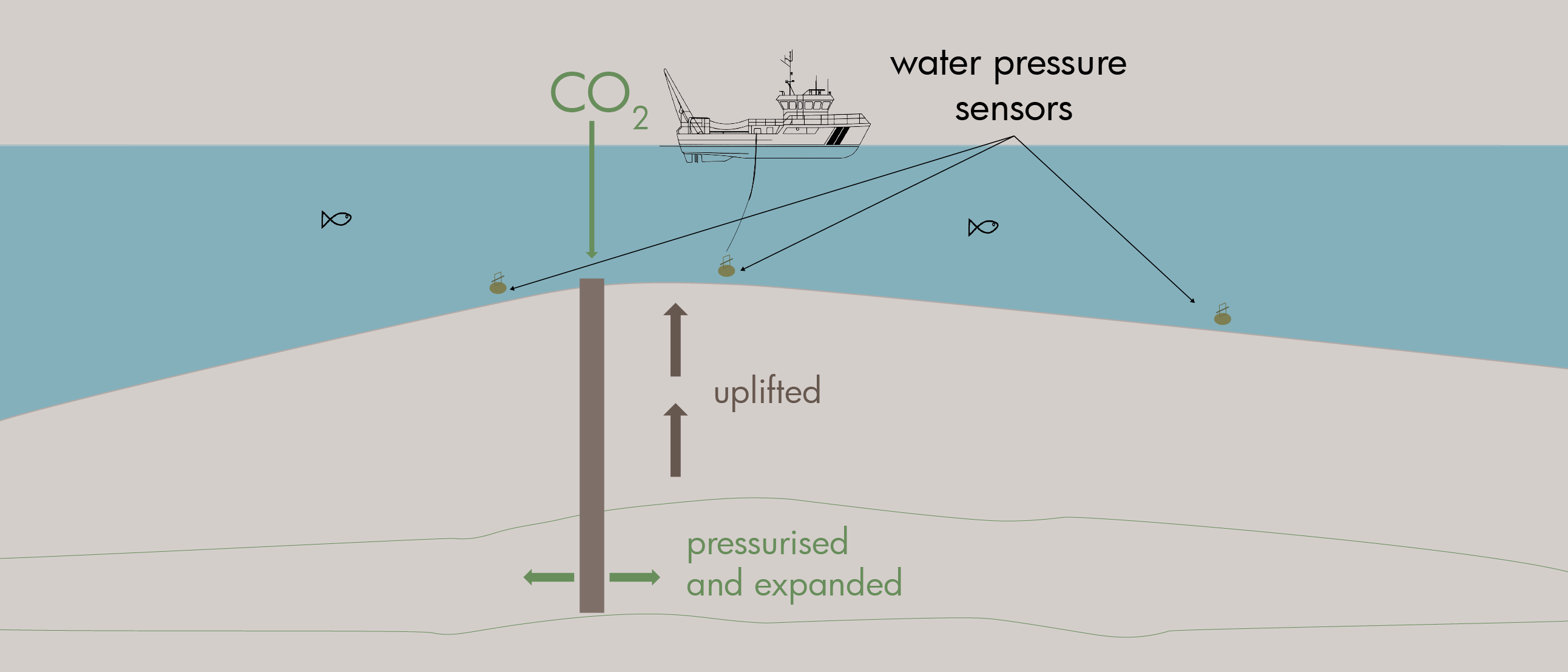

It was the first CCS demonstration in Japan to test CO2 injection at scale. Two injection wells were drilled from a position in the harbour of Tomakomai, a small town on the northernmost island of Japan, Hokkaido. Even though the surface location of the wells was onshore, the wells were drilled at a high angle with a TD location offshore. In addition, two observation wells were drilled, ocean bottom seismometers were placed for the detection of microseismic events, and repeated 3D surveys were carried out to monitor plume migration.

Two very different reservoirs

The CO2 was injected into two different reservoirs: The shallow Moebetsu Formation of Quaternary age at a depth of around 1,000 to 1,200 m and the deeper Miocene Takinoue Formation at 2,400 to 3,000 m.

Initially, the plan was to inject around 200,000 tonnes of CO2 per year into each reservoir, but this had to be revised soon after drilling the injection wells. Especially the Miocene volcanic reservoir turned out to have much lower injectivity of several nano-darcy, where the initial permeability was estimated at 9 to 25 md. It was the other way round for the shallow reservoir, though; anticipated permeabilities were thought to be up to 7 md, but this amounted to several hundreds upon test. For that reason, the maximum injection rate for the Takinoue Formation was revised to 1,000 tonnes per year, whilst the Moebetsu target remained the same.

How much was injected at the end? The injection test ran for more than 3.5 years, but only 300,000 tonnes were injected in total, with slightly more than 300,000 tonnes in the shallow reservoir and only 98 tonnes in the deeper one. This low number overall must also be seen in light of the fact that the system was only operational for less than half the time.

Monitoring

The extent of the CO2 plume in the shallow Moebetsu Formation could be monitored using the repeat 3D seismic surveys. However, the small plume in the deeper volcanic “reservoir” could not be confirmed by the same technology, which was explained by the volume being too low to be detected.

Even though this is not a major surprise – there needs to be a minimum disturbance for a signal to be detected – it does show that it is not always guaranteed that monitoring will pick up the signal. Volumes need to be taken into account, as well as the probability that seismic won’t even be able to detect anything at all despite the volumes, as is the case with the planned Morcambe Bay CO2 injection project in the UK. In that case, gravity measurements are planned to monitor CO2 plume migration instead.