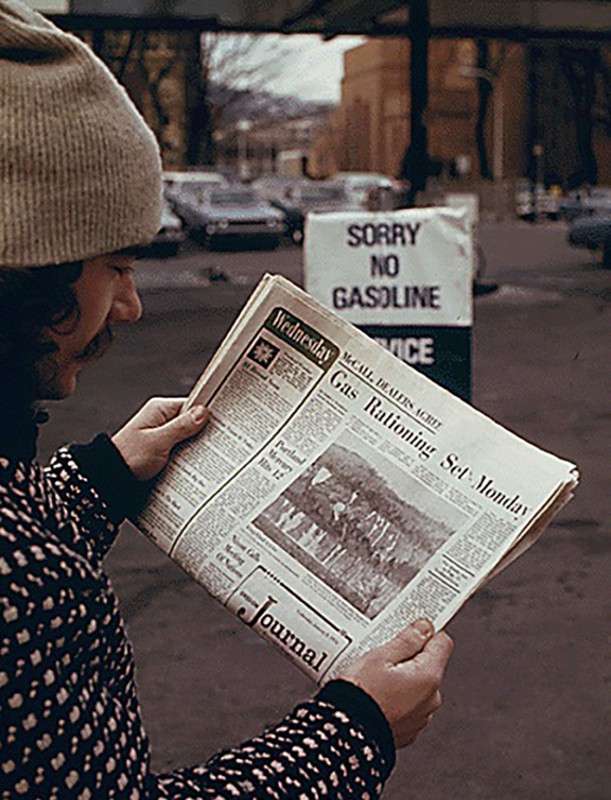

In December 1973, thousands and thousands of cars on many US highways were stuck in traffic jams for miles and for hours. Truckers had stopped the traffic to protest at rapidly soaring gasoline (petrol) prices: in September 1973, gasoline cost 27 cents a gallon; by December it had risen to 50 cents. Gasoline queues and rationing in the industrial nations were a more visible mark of ‘the first oil shock’ in the world. One sign at a gasoline station in the US read: “Gas shortage! Sale limited to 10 gals of gas per customer.” Another sign was even shorter: “Sorry, no gas today”. People in Japan extended their fear of oil shortages to toilet paper, storming the grocery stores in panic to buy as much as possible before they ran out! The 1973–74 oil shortage and spiking gasoline prices were the result of two processes: the rise of OPEC (see ‘The Road to OPEC 1960’ by the same author) and the Arab oil embargo.

US Countdown to 1971

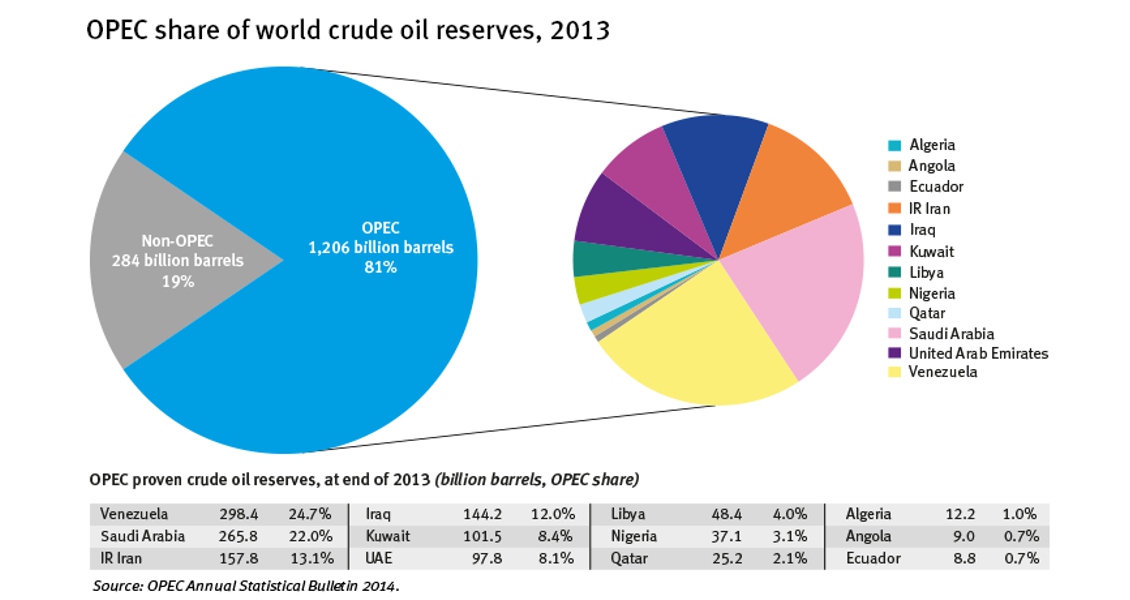

Sale policy displayed on a flag in a gasoline station in Oregon during the winter of 1973–74. (Source: NARA/Wikipedia)The 1950s and 60s were an era of cheap and abundant oil, thanks (largely) to Middle Eastern oil. Between 1948 and 1972, world crude production rose from 8.7 MMbopd to 42 MMbopd; Middle East production rose from 1.1 MMbopd to 18.2 MMbopd. During the same period, the world’s crude reserves increased from 62 to 534 Bbo; Middle East reserves increased from 28 to 367 Bbo – in other words, seven out of every 10 barrels added to the world’s reserves came from the Middle East. All through these years, oil prices remained relatively stable at US $1.8–$2.0 a barrel, while petrochemical and automobile industries flourished at rapid rates. The low oil prices were made possible largely because international oil consortia in the Middle East increased production to catch up with increasing global demand for oil.

Sale policy displayed on a flag in a gasoline station in Oregon during the winter of 1973–74. (Source: NARA/Wikipedia)The 1950s and 60s were an era of cheap and abundant oil, thanks (largely) to Middle Eastern oil. Between 1948 and 1972, world crude production rose from 8.7 MMbopd to 42 MMbopd; Middle East production rose from 1.1 MMbopd to 18.2 MMbopd. During the same period, the world’s crude reserves increased from 62 to 534 Bbo; Middle East reserves increased from 28 to 367 Bbo – in other words, seven out of every 10 barrels added to the world’s reserves came from the Middle East. All through these years, oil prices remained relatively stable at US $1.8–$2.0 a barrel, while petrochemical and automobile industries flourished at rapid rates. The low oil prices were made possible largely because international oil consortia in the Middle East increased production to catch up with increasing global demand for oil.

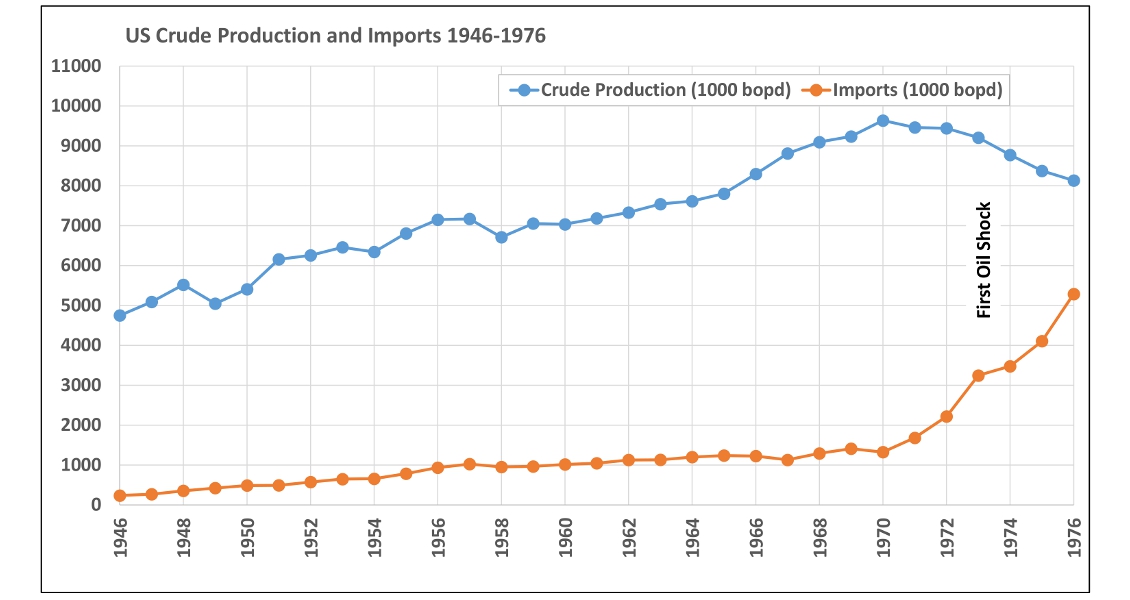

Interestingly, the USA, the world’s largest oil producer and consumer, had decided to rely more on its own domestic resources than on foreign oil. Considering national security measures, in 1954 the US drafted a ‘Voluntary Program’ to reduce its import of oil from outside the Western hemisphere. This, however, did not work. In 1959, US President Eisenhower proclaimed the Mandatory Oil Import Quota Program, restricting US import of crude as well as refined oil to less than 9% of domestic demand (in 1962, the quota changed to 12.2% of domestic production). The independent oil companies in the USA (which all along had lobbied for it) rejoiced, while the major international companies were disappointed.

From 1948 to 1971, US oil reserves grew from 21 to 38 Bbo and its production from 5.5 to 9.5 MMbopd; however, US share of world crude production shrank from 64% to 22%. Indeed, M. King Hubbert (1903–1989), a bright oil geoscientist working for Shell, had made forecasts (dating back to 1956) that oil production in the lower 48 USA would peak in the late 1960s or in 1970. Amazingly, his forecast came true: US production of conventional crude peaked at 3.5 Bbo in 1970.

Decline in US production not only removed significant oil supply from the global oil market but was also accompanied by rapid increases in the US import of oil. In 1973, when President Nixon officially terminated the Mandatory Oil Import Program, the US imported 6.2 MMbopd, compared to 3.2 MMbopd in 1970.

OPEC and Oil Price Surges

During the 1960s, OPEC was not taken seriously by the consortia of major American-European companies. However, changes were soon to come. In September 1969, the 27-year-old Muammar Qaddafi, leading a group of revolutionary young army officers, staged a coup d’état and overthrew King Idris of Libya, a country where 21 oil companies were operating and which supplied one-third of Europe’s oil. In 1970, Qaddafi warned the oil companies in Libya that he needed a better deal. He picked his first battle with Occidental (since all its operations were in Libya) and got an increase of 30 cents a barrel (to $2.53) and a further $0.02 each year for the following five years. Within two months, the other oil companies agreed to similar agreements with the Libyan government, resulting in a majority (54–58%) profit share for Libya. This ushered in a series of oil price increases and renegotiations. In November 1970, the Shah of Iran won a 55:45 agreement with the consortium companies. Kuwait followed suit in the same year.

In January 1971, the oil companies wrote a letter to OPEC, seeking a comprehensive settlement of issues with oil-exporting companies – a sign of the ascending international power of OPEC. Back in December 1970 an OPEC meeting in Caracas had established 55% as a minimum tax rate, and in early 1971 OPEC had threatened a total oil embargo if the companies did not comply with this suggestion. Two negotiation meetings were scheduled, one in Tehran for Persian Gulf oil and another in Tripoli for Mediterranean oil.

On 14 February 1971, the Tehran agreement was signed between six Middle Eastern governments and 22 oil companies for 55:45 profit sharing; it also increased the posted price of oil by about 35 cents a barrel (from $1.80 to $2.18 for light Saudi crude) and promised further annual increases of 5 cents a barrel and 2.5% inflation rate for the following five years. Then on 2 April 1971, the Tripoli agreement (for Libya, Algeria, Saudi Arabia and Iraq) raised the price by 90 cents a barrel (to $3.45) in addition to similar annual increases. The Shah of Iran was furious over leap-frogging prices.

In August 1971, the USA decided to abandon the gold exchange standard, float its currency, and expand its money supplies. This resulted in depreciation of the dollar, and because oil was traded in dollars, OPEC government revenues were reduced. In its September 1971 Beirut meeting, the organisation instructed its members to negotiate price increases with the oil companies in order to offset the decline in the value of the US dollar. This triggered a series of price rises in 1972 and 1973, further adding to the panic over oil politics.

The US government initially welcomed these price surges, mainly because the oil wealth would contribute to the economic development of OPEC nations, which would prevent them from falling into the hands of the Soviet Union. Moreover, a considerable portion of OPEC’s petrodollars would also be spent on Western technologies, weaponry, goods, services and stock investments. The executives of oil companies were also aware of the new realities and were willing to offer more profits, taxes and participation to the oil-producing countries.

The Arab Oil Embargo

As 1973 began, excess oil supply had dried on the international market. In January 1973, the posted price of Saudi Arabian light oil was $2.59 a barrel; by July it had increased to $2.95 as OPEC raised the price in April and June 1973. In September 1973, the OPEC meeting in Vienna decided that Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and UAE (Abu Dhabi), the so-called ‘Gulf Six’, could negotiate as a group with the companies over prices; other OPEC members would do so individually.

On 6 October 1973, on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, Egyptian and Syrian warplanes and soldiers made surprise attacks on Israeli positions, aiming to expel Israel from Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and Syria’s Golan Heights, taken in 1967. Within days of the attacks, Israel mobilised its forces and not only stopped Egyptian and Syrian advances but also began military operations within the enemy’s territories.

Prior to the war, Anwar Sadat, who had succeeded Nasser as Egypt’s President in 1970, had convinced King Faisal of Saudi Arabia to use ‘the oil weapon’ (cutting exports) against countries supporting Israel. Of course, the USA, Israel’s main ally, was high on the list, especially as it was facing declining domestic oil production and increasing demand and imports. The oil-rich Arab governments were looking for a smoking gun, which they found on 14 October, when US Air Force planes carried ammunition to Israel. This was, in fact, a US response to the Soviet resupply of weapons to Syria and Egypt just days before that, but the Arab world was enraged, and the US efforts to arrange a truce between Israel and its Arab neighbours did not mean much.

A man reading about gasoline rationing in a service station in 1974. (Source: NARA/Wikipedia)On 16 October 1973, the Gulf Six unilaterally increased the price of oil from $3.01 to $5.12 per barrel – a 70% increase. The following day, Arab oil ministers decided to use ‘the oil weapon’ against the states who supported Israel, including the USA, Netherlands, Portugal, Rhodesia and South Africa. The embargo involved a reduction x oil production by 5% from the September level with further 5% cuts each month until the Arabs’ political objectives were met. (In reality, the scheduled additional 5% cuts per month were not made.) On 19 October, President Nixon publicly announced a $2.2 billion military and financial aid for Israel. Within a day or two, the Arab countries completely stopped oil shipments to the US, although Iran and Iraq did not join the embargo.

A man reading about gasoline rationing in a service station in 1974. (Source: NARA/Wikipedia)On 16 October 1973, the Gulf Six unilaterally increased the price of oil from $3.01 to $5.12 per barrel – a 70% increase. The following day, Arab oil ministers decided to use ‘the oil weapon’ against the states who supported Israel, including the USA, Netherlands, Portugal, Rhodesia and South Africa. The embargo involved a reduction x oil production by 5% from the September level with further 5% cuts each month until the Arabs’ political objectives were met. (In reality, the scheduled additional 5% cuts per month were not made.) On 19 October, President Nixon publicly announced a $2.2 billion military and financial aid for Israel. Within a day or two, the Arab countries completely stopped oil shipments to the US, although Iran and Iraq did not join the embargo.

On 22 October the United Nations brokered a ceasefire which went into effect on 25 October. Nevertheless, the war pushed oil prices even higher; on 22 December 1973, an OPEC meeting set the oil price at $11.65 a barrel. The Shah of Iran, who had hosted the meeting in Tehran and had suggested the new price, was jubilant. In 1970 oil exports generated $7.7 billion for OPEC governments; by 1974 this revenue had increased to $88.8 billion; the age of the petrodollar economy (for good or bad reasons) had begun.

In March 1974, the Arab oil ministers ended the embargo against the USA and in June that year they lifted it against the remaining countries, restoring exports to September 1973 levels.

In hindsight, the Arab oil embargo did not cause a significant shortage of oil supply. According to Daniel Yergin (The Prize), it removed about 4.4 MMbopd from the international market, and only for five months. This amounted to 9% of the total 50.8 MMbopd in the non-communist world. However, the ‘oil weapon’ was something the world had not seen before; it thus created uncertainty, speculation and fear not only among industrial countries, which were nervous about being subjected to the embargo, but also among ordinary people whose consumption of oil had rapidly increased.

Aftermath of the First Oil Shock

The early ’70s oil shock happened after two decades of stable, low-price oil. It changed the world in a number of important ways. First, it gave confidence and power to many OPEC governments to take control of their oil resources either by outright nationalisation like Iraq, or by participation (phased buy-out) as in the case of Saudi Arabia.

Second, it strengthened a growing sense of environmental protection in Western nations. Earth Day was first celebrated on 22 April 1970 across the USA. The Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth (1972) offered a gloomy computer simulation of economic and population growth in a world of finite resources. In a similar tone British economist E. F. Schumacher published Small is Beautiful (1973), calling for small, appropriate, people-oriented technologies. Car manufacturers were regulated to increase the fuel (gallon per mile) efficiency of their vehicles.

Third, energy security rose to a national priority. In order to prepare for any future oil shortage, many Western countries launched emergency oil stockpiling programmes. In 1977, the US Department of Energy was established, one of whose tasks has been to maintain the strategic petroleum reserves at a total capacity of 727 MMbo, the largest of its kind in the world.

Fourth, many Western countries and international oil companies were motivated to look for alternative oil basins around the world, while higher oil prices gave financial capability for oil companies to explore and produce from relatively expensive basins around the world. Alaska’s North Slope and North Sea (where oil had been discovered in 1968 and 1969, respectively) thus became new, successful frontiers for oil exploration and production.

Finally, the 1973 oil shock shifted the centre of policymaking on oil prices, production quota, and spare supply from the USA to the Middle East. It also set in motion a series of oil shocks (the second in 1979–80 and the third in 2004–05) and oil market crashes (for example, in 1985, 1999, 2008 and 2014). The story of oil booms and oil busts continues.