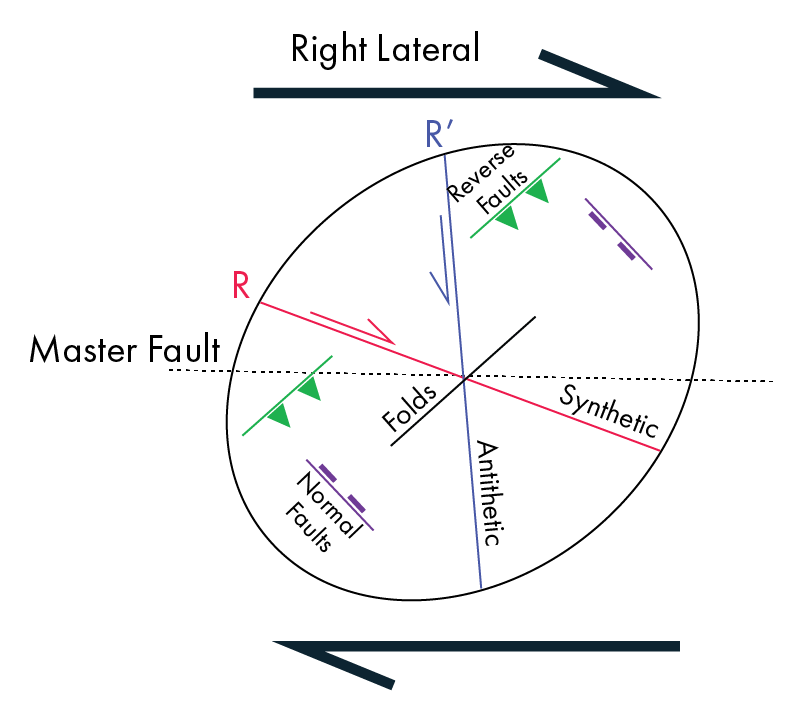

Before the advent of 3D seismic data in the 1980s and 2D seismic in the 1970s, subsurface geologists typically depicted or interpreted faults as vertical or nearly vertical. Consequently, these faults were often kinematically classified as strike-slip, despite the actual dip being unknown. The seminal work of Wilcox and Harding in the early 1970s on strike-slip faulting, particularly their development of the strain ellipse, gained widespread traction. This model explained the orientation and types of structures forming along major strike-slip fault zones, termed “wrench faults.” Geoscientists enthusiastically applied the strain ellipse to interpret fault azimuths on maps, leading to a trend where many faults were assumed to be strike-slip.

Before the advent of 3D seismic data in the 1980s and 2D seismic in the 1970s, subsurface geologists typically depicted or interpreted faults as vertical or nearly vertical. Consequently, these faults were often kinematically classified as strike-slip, despite the actual dip being unknown. The seminal work of Wilcox and Harding in the early 1970s on strike-slip faulting, particularly their development of the strain ellipse, gained widespread traction. This model explained the orientation and types of structures forming along major strike-slip fault zones, termed “wrench faults.” Geoscientists enthusiastically applied the strain ellipse to interpret fault azimuths on maps, leading to a trend where many faults were assumed to be strike-slip.

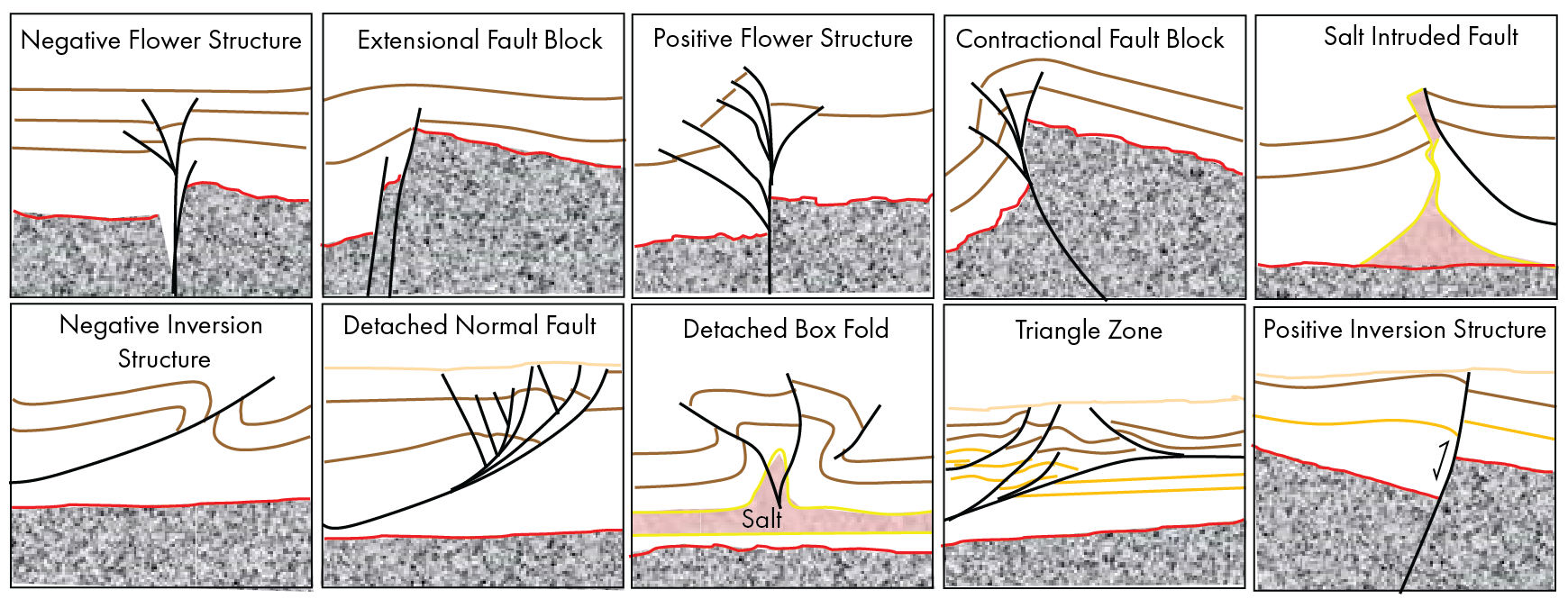

The strike-slip model became so dominant that Harding published a follow-up paper in 1990, cautioning against its universal application. He outlined alternative interpretations for structures resembling positive or negative flower structures, particularly without 2D or 3D seismic data. These alternatives, illustrated in the figure below, included contractional or extensional fault blocks, faulted detachment folds, salt structures, and more.

Interpreters should consider more than just geometry when analyzing faults. Factors such as deformation timing, tectonic setting, and stress regime are critical. For instance, flower structures are unlikely in rifting environments, where normal faulting – possibly at high angles – is more common. Similarly, in fold-and-thrust belts, a “pop-up” structure might indicate a faulted detachment fold rather than a flower structure. Advances in 3D seismic have refined our understanding of faulting since the 1970s, but this serves as a reminder for geologists, especially in frontier basins or when relying solely on well data, to integrate kinematics, tectonics, and stress orientations into their interpretations.