While helpfully descriptive in many areas, it is riddled with assumptions and technical misconceptions; and it is very forgiving of the foibles of the author’s rural Pennsylvanian associates. That said, this is probably how many opponents of the shale revolution think. It came out in 2011, a long time ago in shale terms; but the issues faced are now being met all around the world.

Unstoppable Momentum

I picked up a copy in 2011 in Pittsburgh airport while returning from a DUG (Developing Unconventionals) East conference which had seethed with energy and new ideas. Most importantly, a Washington heavyweight had been the lead-off speaker (from the US Environmental Protection Agency, no less) and, exuding the quiet confidence of the truly powerful, intoned two or three times from a prepared speech that the shale revolution was in the ‘national interest’, vital to the ‘national security’ of the United States – but it had to be done right. Obama was on side; the applause was that of relief.

There seemed an unstoppable momentum – and in truth there is.

The shale revolution has drastically increased the world’s economically recoverable hydrocarbon resource base. It will take time to spread but in the meantime, US production alone will bring radically lower oil and gas prices worldwide. 2011 was a heady time for those who had watched the evolution of the shale revolution.

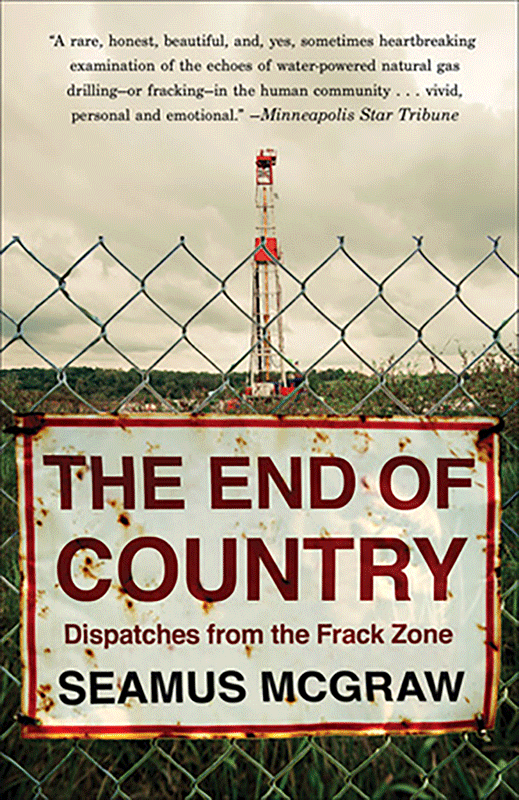

But there was trouble brewing on the environmental side; The End of Country appeared just after the film Gasland came out. As Professor Terry Engelder of Penn State demonstrated in his AAPG Distinguished Lecturer series (see GEO ExPro Vol. 11 no. 4), Gasland is more fiction that fact. Nevertheless, it has still helped convince a sizeable part of the environmental movement to erect barriers to the use of shale gas, thus slowing the wholesale switch from coal to shale gas worldwide – which just happens to be the only way to make needed CO2 reductions in the short time-frame that environmentalists, almost to a person, say is needed. This seems perverse.

Local Insights

The End of Country is important because very little has been written on fracking from the bottom looking up – the place where public opinion is formed. It helps fill this gap by presenting the facts as seen through the eyes of an ‘everyman’. McGraw was a reporter of no great accomplishment or geoscience expertise, but he was a keen observer of fracking operations on the ground – and in the minds of his neighbours. He has strong memories of growing up in north-east Pennsylvania, an area where naturally occurring gas seeps are well known, and lived a few hills over from Dimock, Pennsylvania, the depressed farming area brought to prominence by Gasland.

He is also a man with conflicted interests, who supports selling drilling rights on the family farm and at the same time has the “what will all this mean for us?” concerns of everyman. Upon my re-reading, the book still exudes that same initial feeling of a story well told with somewhat forced balance, imbued with insights that only a local could provide. It describes the first wave of landmen coming to town with their usual sales talk, but fails to evoke more than mild disapproval of their missteps; it talks about misunderstandings turned to principle, then to revenge and acts of expensive nuisance; it speaks mostly of local motivations and fears, but it is clear that the preservation of the ‘peace and quiet’ of a very beautiful area conveniently located a mere 150 miles from New York City plays a bigger role.

It will evoke a peculiar mixture of admiration with a nagging feeling that nothing substantially threatening has been described – yet the anxiety and concern are palpable. The End of Country tracks the transformation of the mundane into a powerful political force – one capable of setting back fracking policy in jurisdictions where political leadership is weak.

So, if you want or need to understand these forces, read this book.