“To this day I remember the moment that I was told that the oil in our prospect is indeed sourced from the Kimmeridge Clay.”

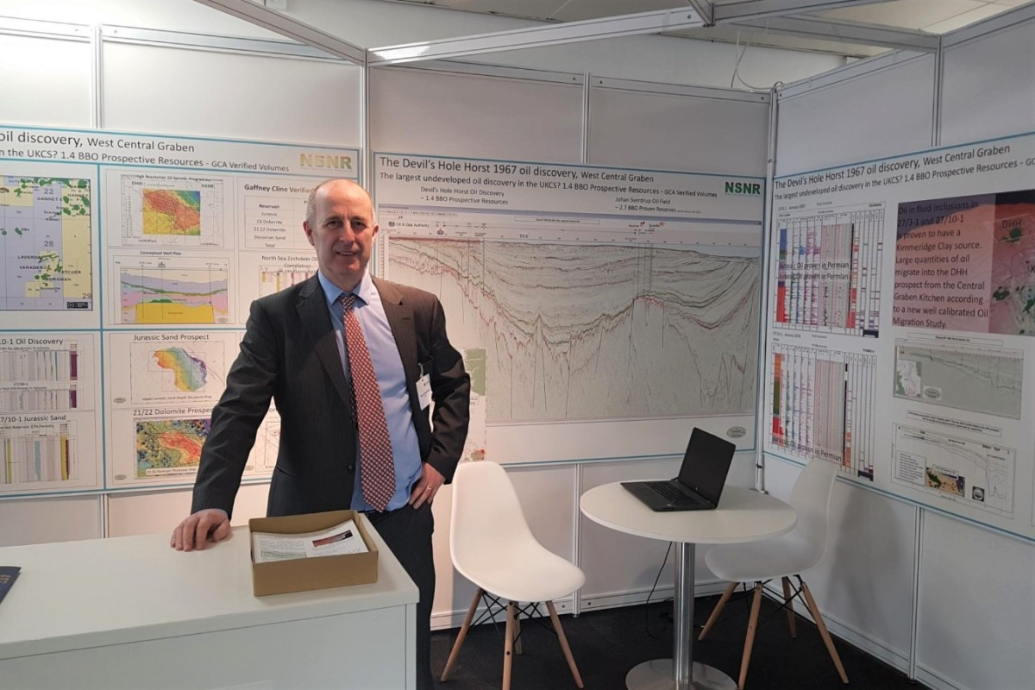

It was a very important moment for Niels Arveschoug, CEO of North Sea Natural Resources and the owner of Licence P2321 covering the Devil’s Hole Horst prospect in the Central North Sea.

Hear the latest news from Niels Arveschoug on the Devil’s Hole Horst Prospect at Prospex in London next week. Prospex is now integrated with the Petex Conference.

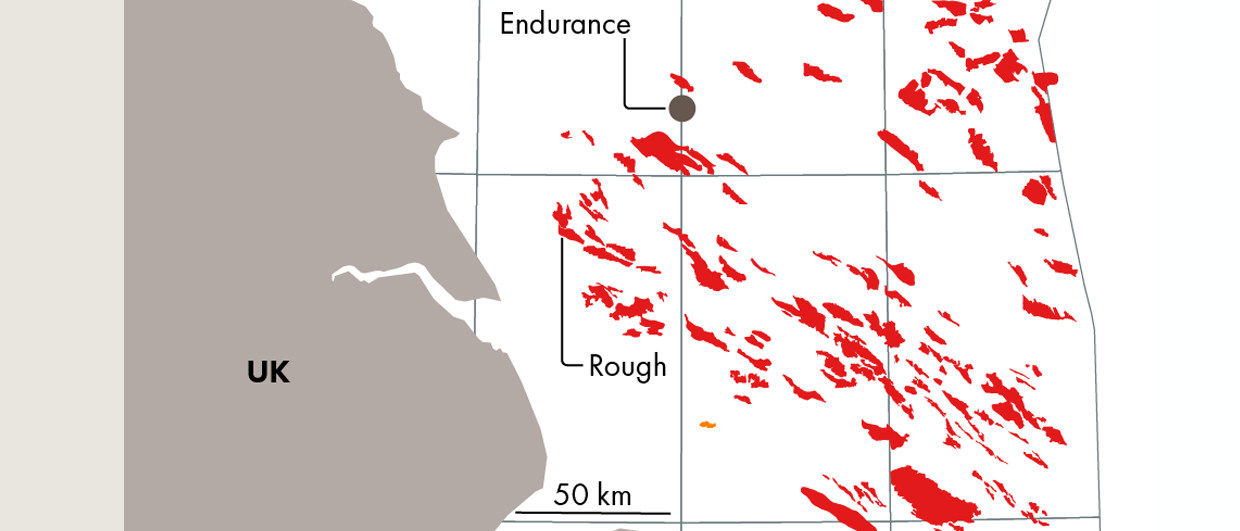

“With this evidence in hand, we were able to conclude that oil did migrate over a distance of about 70 km to the west into what we have mapped as one of the last remaining undeveloped mega-closures on the UK Continental Shelf,” Niels adds.

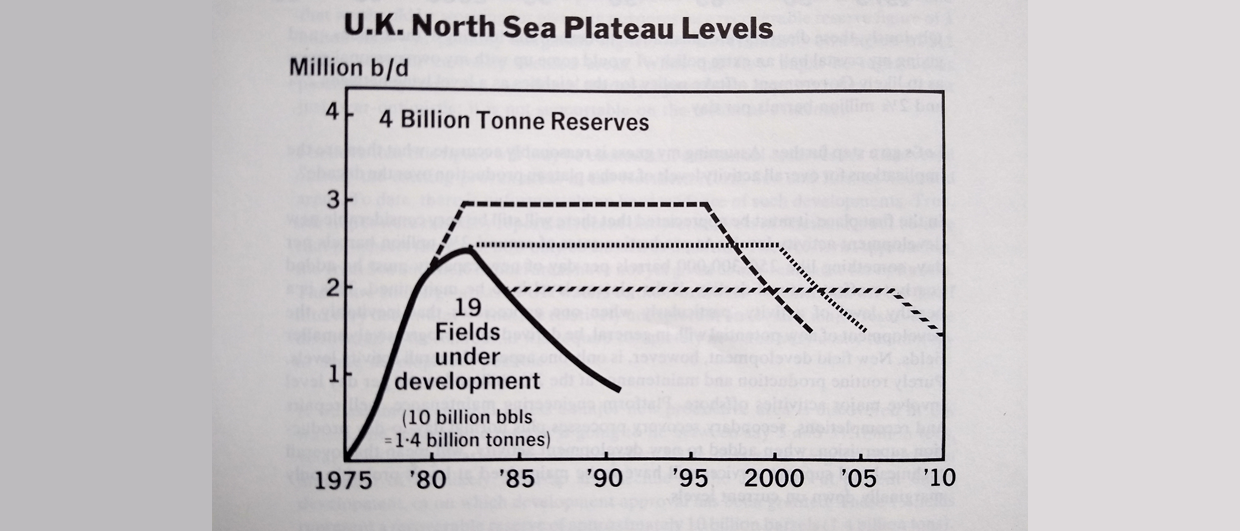

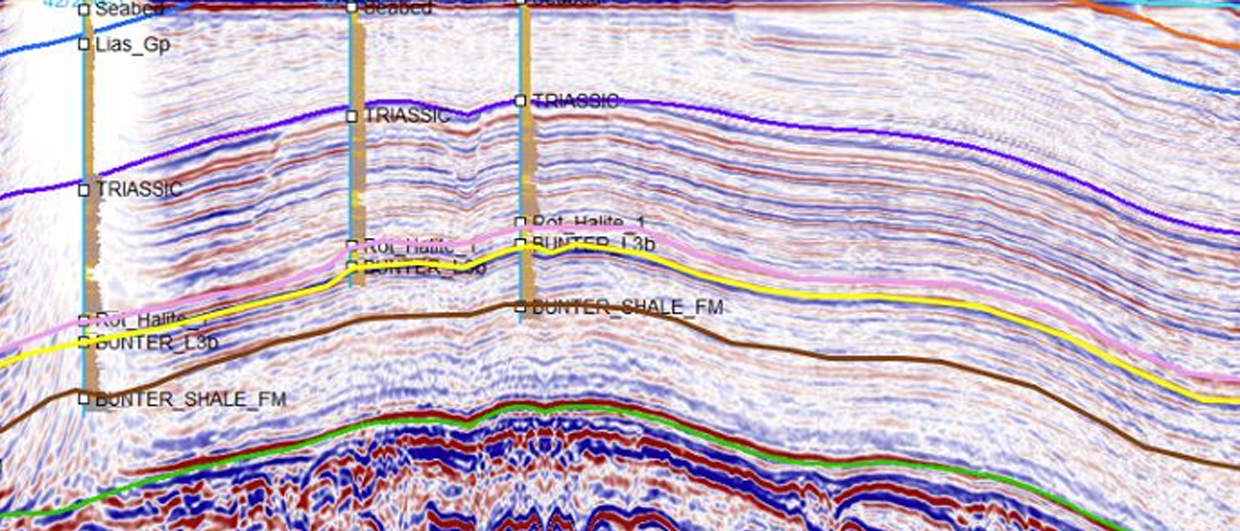

It is not the first time that the structure appeared onto the exploration radar though. It featured in the early days of North Sea exploration, when mapped on what must have been the first generation of 2D seismic lines.

“In those days (late 1960’s), companies were only chasing the Rotliegend aeolian sand play in an attempt to find a Groningen field equivalent,” Niels explains. When the three wells drilled (by Amoco/Gas Council/Amerada/Texas Eastern and Burmah/BP/Hamilton) in the close vicinity of what has now been mapped as the closure did not return what they were after, interest soon dissipated.

It took almost 50 years before the structure received new interest, inspired by the discovery of the Johan Sverdrup field in Norway (which had also been overlooked for 40 years).

How did the Devil’s Hole Horst get its name?

It was in the 1850’s that fishermen reported their nets missing in an area where the seabed dropped from 80 to around 200 m in depth. Then called the Devil’s Hole, the geological explanation for the depression is either a glacial scour or a fault soling out in the Zechstein salt in the subsurface.

The discovery of oil in Johan Sverdrup came as a surprise to many geologists who had previously dismissed the idea of long-distance migration from the Kimmeridge kitchen in the Viking Graben up to the Utsira High.

With the news percolating through in 2011 when Niels was working in Stavanger, he immediately knew where else to look for a similar structure, thanks to his long career in the basin and his North Sea regional expertise.

Regional exploration key

“Even though the North Sea can be regarded as a mature and data-rich basin, regional exploration is still key to map structures that can go unnoticed when only focusing on near-field exploration,” Niels says. He mentions that the Britannia field was “discovered” five times because the structure was overlooked due its size. “It is important to see not only the elephant’s ear, but the entire elephant,” he adds.

The Devil’s Hole Horst can certainly be regarded as an elephant.

With the Johan Sverdrup results coming in, Niels immediately projected the concept to the western platform of the Central Graben and quickly realised that the Devil’s Hole Horst may well be in a similar setting as Johan Sverdrup.

Well 27/3-1, the first one that was drilled on the structure in 1967, did find oil but in the Zechstein rather than in the anticipated Rotliegend. With the drill stem test failing, and the second and third wells reported dry, it is no surprise that the area was written off at the time.

However, based on new high tech geochemistry studies, Qemscan cuttings analysis, revised petrophysics with redigitised logs, high resolution 2msec reprocessing of modern OGA regional seismic, mapping and seismic interpretation, these well results can now be put in context to define a decent giant oil prospect. A very decent one, with 1.8 billion barrels of oil being potentially present in both the Upper Jurassic Fulmar sand onlapping the structure as well as the underlying Zechstein dolomite.

“Before the pandemic hit, we were having good traction with a number of operators for a farm-out deal,” Niels says. “We are now seeing buoyant energy prices and confidence returning”.

The next step in the process is to acquire seismic and to drill two wells on the prospect. “We have got a seismic permit for a licence-wide survey,” Niels explains, “now it is a matter of securing a farm in partner to carry out the work with and then hopefully test the structure in early 2023.”

HENK KOMBRINK