“We desperately need substantial amounts of manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper to build electric cars and power plants,” says Hans Smit to The Guardian. Smit is chief executive of Florida’s Ocean Minerals and has announced plans to mine for nodules.

“We cannot increase land supplies of these metals without having a significant environmental impact. The only alternative lies in the ocean.”

However, “Other researchers disagree – vehemently,” as voiced by Robin McKie in The Guardian.

Huge resources

In a recent article (August 29, 2021), the well-respected newspaper discusses pros and cons related to deep-sea mining of polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean. The backdrop being that more than 20 exploration contracts have been awarded by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). ISA regulates and controls all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area “for the benefit of mankind as a whole”.

Recent estimates suggest that “there is six times more cobalt and three times more nickel there than in the world’s entire land-based reserves” over a flat sea-bottom covering some 4.5 million square kilometres, at depths between 4,000 and 5,500 meters.

At NCS Exploration – Deep Sea Minerals in Bergen, October 20-21, one full session is devoted to “Mineral Resource Inventory”, including a talk by John Parianos who used to be Exploration Manager at Nautilus Minerals.

Plumes may destroy ecosystems

Environmentalists argue, however, that “mining deep-sea nodules would be catastrophic for our already stressed, plastic-ridden, overheated oceans. Delicate, long-living denizens of the deep would be obliterated by dredging. At the same time, plumes of sediments, laced with toxic metals, would be sent spiralling upwards to poison marine food-chains”.

The Guardian refers to a recent report by the international conservation charity Fauna and Flora International, which states that deep-sea mining “will also produce sediment plumes which will disrupt ecological function and behavioural ecology of deep-ocean species, smothering fundamental ecosystems.

At NCS Exploration – Deep Sea Minerals in Bergen, October 20-21, Professor Thomas Peacock at MIT will give a talk entitled “Deep-sea mining and Sediment Plumes”.

This is also why WWF earlier this year called for a global moratorium on deep-sea mining “unless and until the environmental, social and economic risks are comprehensively understood”.

However, the mining companies argue that “the impact of nodule mining will be magnitudes less than the equivalent impact of the mining on land for the volumes of metals we will need in the future”.

The correctness of this statement will be addressed in one of eight sessions (“Licence to operate”) in the forthcoming conference NCS Exploration – Deep Sea Minerals in Bergen, October 20-21.

Recycling as a substitute

It’s an understatement that deep sea exploration and mining is a highly polarised dispute. “On one side, proponents of nodule extraction claim it could save the world, while opponents warn it could unleash fresh ecological mayhem.”

Opponents of deep-sea mining point to recycling as a means of reducing the need for critical minerals like manganese, cobalt, nickel and copper. The Guardian refers to Professor Richard Herrington, head of earth sciences at the Natural History Museum, London, who says that “recycling is going to be important, but it will not be enough on its own”.

Part of the story is also that recycling percentages vary a lot according to the metal in question. According to a report entitled “Recycling Rates of Metals” recycling rates of metals are in many cases far lower than their potential for reuse. “Less than one-third of some 60 metals studied have an end-of-life recycling rate above 50 per cent and 34 elements are below 1 per cent recycling.”

Deep-sea mining will happen

“On its own, recycling these metals is unlikely to provide the ingredients we need for these devices, so mining is going to be important. On land it is associated with all sorts of problems and eventually there will be a push for deep-sea mining – and in the end it [deep-sea mining] will happen. That means we need to get as much information about its impact, so we are best placed to limit the damage,” says Andrew Sweetman, professor of deep-sea ecology at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, to The Guardian.

Mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone is certainly not imminent. Chris Williams, managing director of UK Seabed Resources, for example, does not expect commercial operations to start until the end of this decade. That may potentially be good news for the environment.

“I am confident we will be able to show that extracting polymetallic nodules will have a lower impact on the environment than will be the case with the opening of new mines on land or the expansion of existing ones,” Williams says to The Guardian.

The article in The Guardian («Is deep-sea mining a cure for the climate crisis or a curse?») reminds us that this decade will be extremely interesting with respect to how the future energy demand – and hence mineral demand – will be met.

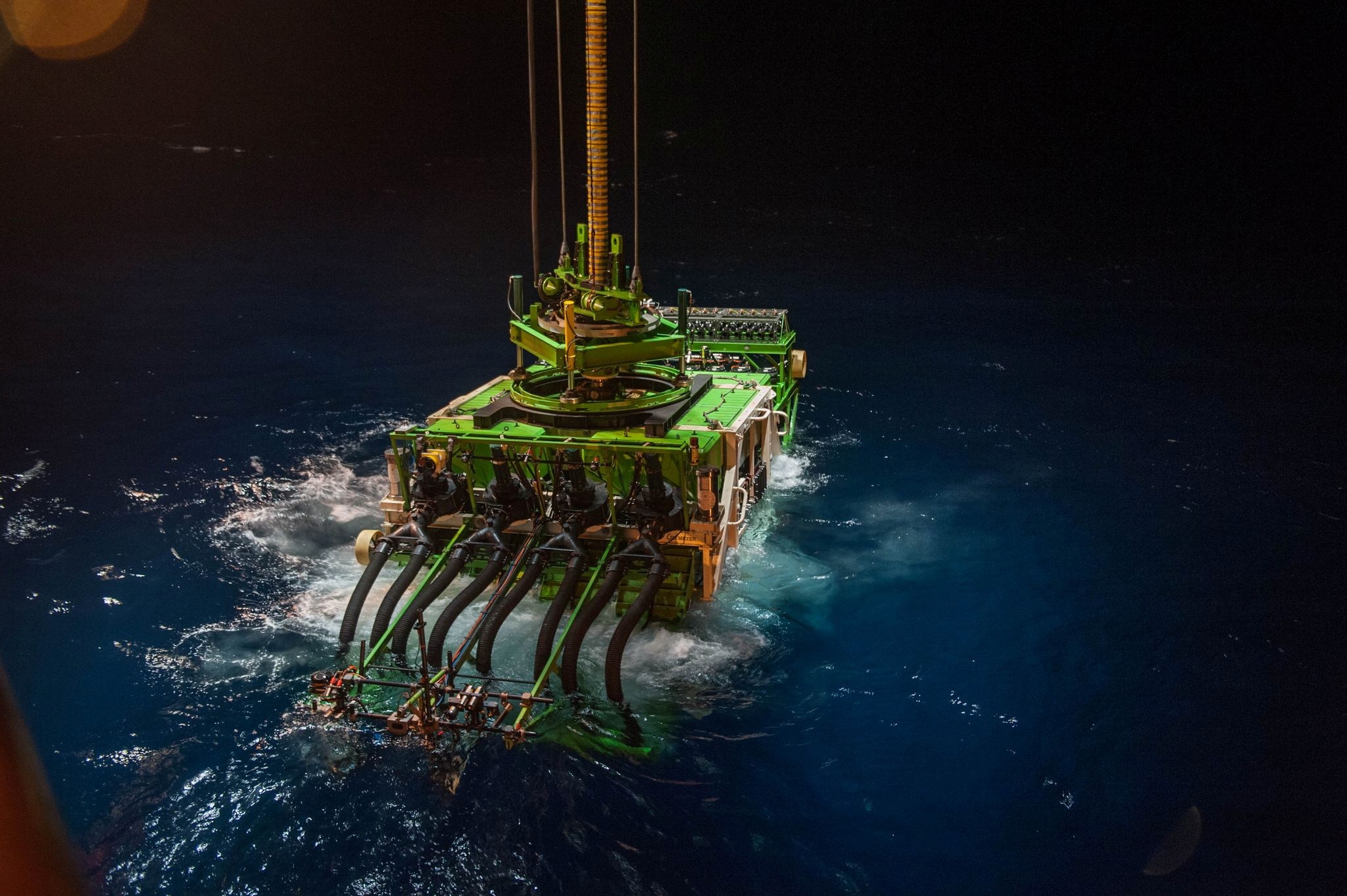

Polymetallic nodules can be found in the abyssal plains of all major oceans at water depths between 4,000 and 6,000 m. However, they are most abundant in the Central Pacific Ocean in an area known as the Clarion Clipperton Zone (“CCZ”). The composition and size of nodules varies slightly depending on where they are found. On average each is rich in nickel (1.3%), cobalt (0.2%), manganese (27%) and copper (1.2%) and is the size of a potato. Info by GSR.

HALFDAN CARSTENS