The history of the world’s three great monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – has unfolded in the so-called Holy Land, a starkly rugged landscape that stretches from the highlands in Jordan to the Mediterranean and Red Seas. This terrain has been largely shaped by the Dead Sea Transform, a major fault system that forms part of the complex boundary between the African and Arabian plates.

This left-lateral strike-slip system runs from the Maras Triple Junction in southern Turkey to the northern end of the Red Sea. South of Lebanon it consists of a series of left-stepping, en-echelon faults; motion along these independent strands has produced 105 km of left-lateral displacement plus a smidge of extension, thereby creating a series of pull-apart basins. These lie well below sea level because they are on the hanging walls of normal faults that accommodate the small component of divergence produced in the gaps between the left-stepping strike-slip faults. By contrast, a combination of mantle heat and isostatic flexure has raised the blocks on the adjacent normal fault footwalls to elevations of 700–1,200m above sea level, creating a relatively moister climate that sustains much of the population in both Jordan and Israel. The transtensional nature of the transform’s southern portion, where the fault system runs through the centre of the Dead Sea, creates the area’s rift-like horst-and-graben landscape.

As a result of the region’s active tectonism, the Holy Land is filled with distinctive geological and geographic features that govern the events related in many memorable stories contained in the holy literature of all three religious traditions. Mohammad, the founder of Islam, grew up in Mecca, a sacred city nestled in the hills that comprise the uplifted eastern flank of the Red Sea Rift, the more purely extensional portion of the plate boundary that lies south of the Dead Sea Transform. The waters that fill the Sea of Galilee, the world’s lowest-elevation freshwater lake, and the site where Jesus, Christianity’s prophet and founder, miraculously walked on water, come from the moisture that falls on the elevated plateaus. Jerusalem, the Holy Land’s beating heart, stands on the western plateau. The Jordan River flows southward along the axis of the Dead Sea Transform, conveying water from the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea, the hypersaline lake whose -429m shoreline comprises the planet’s lowest exposed land.

Given the Dead Sea Transform’s role as the Holy Land’s master sculptor, we decided to complete a circuit around its southern half to see its artwork for ourselves. Our trip began in Amman, Jordan’s bustling capital, which is located at 1,000m elevation on the Dead Sea pull-apart’s uplifted eastern flank, and ended in Jerusalem, 700m above sea level on its west flank.

The King’s Highway

The first part of our journey led southward along the King’s Highway, the modern asphalt rendition of an ancient trade route that ran along the spine of the Dead Sea Transform’s eastern plateau, a terrain steeped in history. In the small city of Madaba, St. George’s Church houses a 6th-century mosaic map of the Holy Land, believed to be the oldest such map in existence. Nearby Mount Nebo is the place where Moses, after leading the Israelites north from Egypt, caught his first – and only – glimpse of the Promised Land before he died. Today this popular attraction offers panoramic views of the Dead Sea nestled in the pull-apart basin 1,100m below.

35 km south of Madaba lie the ruins of Machaerus, Herod the Great’s hilltop fortress, which was built atop a horst block surrounded by deep ravines. It was here that Herod II’s daughter Salome danced for her father, extracting John the Baptist’s beheading as her price. The hilltop and adjacent plateau surface are composed of Cretaceous to Eocene limestone deposited in the Neo-Tethys Sea.

This same limestone is also on display in Wadi Mujib, the impressive 600m-deep ‘Grand Canyon of Jordan’ that dissects the plateau 52 km further south; the wadi’s walls consist of cream-coloured limestone from top to bottom. A few hills of black basalt that rise to the south-east testify to the crustal thinning and heating the area experienced during the formation of the Dead Sea pull-apart basin.

The King’s Highway was a primary battleground during the 12th-century religious wars between Christian Crusaders and Saladin’s Muslim armies. The Crusaders used the area’s limestone to build the impressive strongholds of Karak and Shobak to defend themselves during their raids. Both castles make worthwhile stops along the drive.

The King’s Highway’s undisputed highlight, however, is the magnificent ancient city of Petra (GEO ExPro Vol. 10, No. 4). In contrast to the Neo-Tethyan limestone that underlies the gateway town of Wadi Musa, the up-flexed rift flank to the west consists of Cambrian arkosic sandstone belonging to the underlying Ram Group. The Nabateans, a semi-nomadic Arab tribe that controlled the region’s lucrative incense trade, carved the grand city from this rose-coloured rock between the 4th century BCE and the 2nd century CE.

Reaching Petra entails a walk or horse-drawn carriage ride through the dramatic Siq slot canyon, which in places is a mere 3m wide, before it opens up to a breath-taking view of the Treasury, one of Petra’s most impressive (and, thanks to Harrison Ford, one of its most famous) rock-hewn monuments.

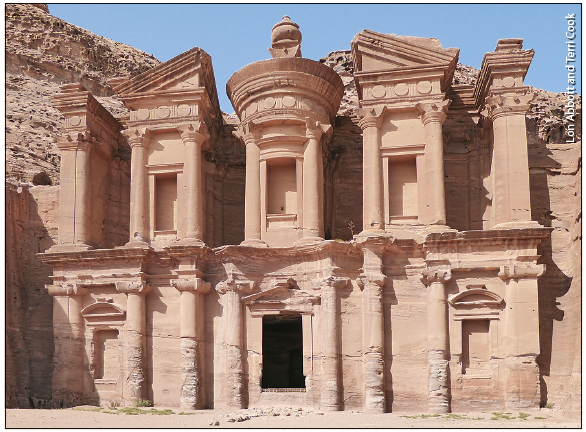

Petra’s other signature structure is the Monastery, a temple dedicated to King Obodas I, who reigned in the 1st century BCE. Unlike most Petra structures, which are tucked into shady canyons, the Monastery is dramatically perched at the edge of the flanking escarpment. The nearby ‘Grand Canyon Overlook’ boasts a stunning panoramic vista of the pull-apart basin 800m below. The escarpment comprises Ram Group sandstone underlain, across the Great Unconformity, by dark Precambrian basement. This basement consists of volcanic rock erupted 550 million years ago on the floor of an earlier pull-apart basin, nearly identical to the modern one visible below.

Coral Reefs and Salt Domes

South of Petra the highway descends from the plateau, weaving its way through a basin-and-range landscape to the coastal city of Aqaba. Due to the hyper-arid climate, the area is nearly devoid of vegetation; each range consists of naked white granite intruded by criss-crossing black diabase dykes that collectively comprise Jordan’s Late Precambrian foundation. The city of Aqaba lies at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, a narrow arm of the Red Sea that has flooded the Dead Sea Transform’s three southernmost pull-apart basins.

Jordan’s 26-km-long stretch of Red Sea coastline is an important tourist attraction thanks to the luxuriant coral reefs that thrive in the exceptionally clear, warm water. Stunning reefs lie just metres off the beach, making the area an easily accessible snorkelling and diving locale.

After snorkelling, we crossed the international border to Eilat in Israel and headed north along the Dead Sea Transform’s western side through the desiccated Arava Valley. Along the way, we stopped to see Mount Sodom, an 11-km-long salt dome that shares its name with the biblical city that God destroyed using fire and brimstone. The city probably flourished thanks to the local sulphur-rich asphalt, which was highly prized for its role in mummification.

Ancient Earthquakes and Salty Soaks

The last leg of our journey continued northward along the transform’s western flank to the holy city of Jerusalem. Along the way, we stopped to soak in the Dead Sea, whose buoyant waters have a dissolved mineral concentration nine times greater than the ocean. Water diversions from the Jordan River have caused the Dead Sea’s surface height to drop 39m since 1930 and triggered the opening of thousands of sinkholes due to dissolution of the lake’s salt substrate. Together, these phenomena have made it increasingly difficult to reach the shoreline, so bathers flock to the resort area of Ein Bokek to float in evaporation ponds owned by Dead Sea Works, one of the world’s largest producers of evaporite minerals.

Another of Israel’s biggest tourist attractions, the ancient fortress of Masada, is perched atop a horst block 17 km north of Ein Bokek. It is another of Herod the Great’s fortresses, built between 37 and 31 BCE, that Jewish zealots seized in 67 CE during the first Jewish-Roman war. The Romans patiently constructed a siege ramp atop a small bedrock spur that links Masada to the nearby Judean Plateau. Six years later, they rolled a battering ram up this ramp and used it to breach the fortress walls.

The Masada horst is ringed by 100m-high cliffs, only breached by two hiking trails. The Roman Ramp trail entails a moderate 15-minute walk from the Judean Plateau to the west; the much more strenuous Snake Path ascends 270m from the Dead Sea basin to the east. Snake Path climbers traditionally opt for a pre-dawn ascent to beat the heat and enjoy the commanding sunrise view.

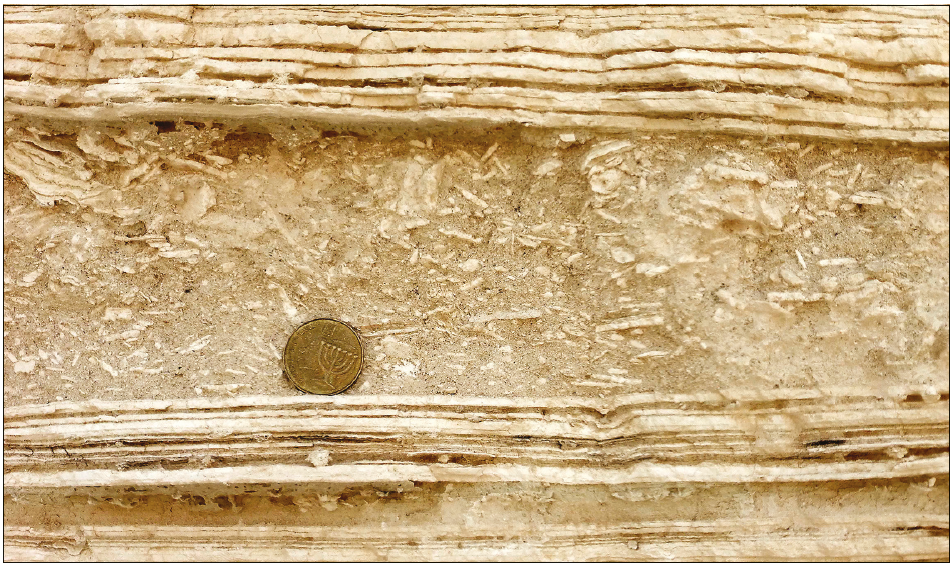

We were excited to explore the sedimentary evidence of ancient earthquakes hidden in obscure arroyos cut through the Lisan Formation below the mountain. This formation consists of varves deposited between 70,000 and 12,000 years ago in Lake Lisan, a larger version of the Dead Sea that also encompassed today’s Sea of Galilee. Identical millimetre-thick varve couplets accumulate on the floor of today’s Dead Sea, composed of clastic detritus that washes into the lake during winter storms, alternating with aragonite that precipitates during intense summer evaporation. In places the Lisan Formation’s varves are interbedded with fractured and folded beds that record sediment liquefaction and slumping that occurred during an ancient earthquake. Scientists have used these ‘seismites’ to construct a 50,000-year earthquake record for the Dead Sea Transform, the longest continuous such record on Earth.

Human and Geological Monuments

The lush oasis of Ein Gedi is perched on the banks of the Dead Sea 21km north of Masada. Here two fault-controlled canyons carved by spring-fed streams crease the Judean Plateau. The streams tumble down beautiful, travertine-encrusted waterfalls and sustain local wildlife, including hyrax and Nubian ibex, in the otherwise harsh and unforgiving landscape.

From the oasis it is an 83-km trip to Jerusalem, the heart of the Holy Land and one of the world’s most historic cities. Its main attractions are associated with stories from all three major religions; most famous is the Temple Mount, whose iconic Dome of the Rock was constructed by Muslim caliph Abd al-Malik between 688 and 691 CE. The dome was built atop the site where, according to Jewish tradition, Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son and where Herod’s Second Temple once stood. According to Muslim tradition Mohammed also ascended to heaven from this same spot. Christian pilgrims retrace Jesus’ path to his crucifixion, beginning just outside the Temple Mount’s north wall.

Historic Jerusalem, and the rest of the landscape upon which the Holy Land’s unparalleled history has unfolded, is a monument to human as well as geologic history.