“LinkedIn seems to be the place to brag about your career successes,” says Luke Johnson from TRACS International in this video.

But sometimes, it is things that went wrong that can teach so much more. That certainly applies to the lesson Luke learned when he helped drill a well as a wellsite geologist and called coring point too early.

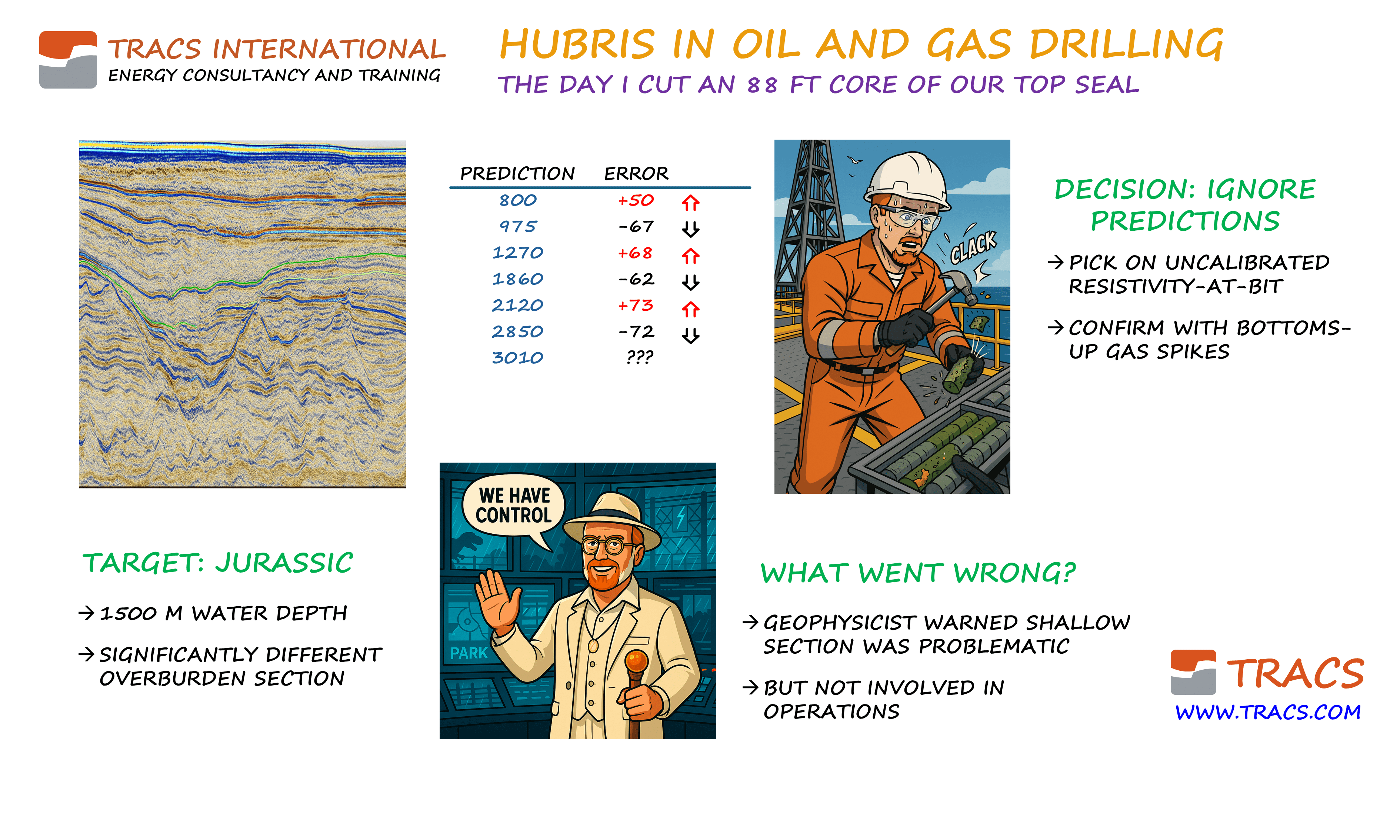

We are in deep-water offshore north-western shelf Australia. The target of the well is an Upper Jurassic lowstand sandstone unit, slightly uncommon in an area where Triassic sands traditionally dominate as the main reservoir.

Even more uncommon is the prospect’s overburden, as can be seen in the image below in the top left. “As the geophysicist in our team explained,” Luke says, “the canyon-style feature carried a great deal of uncertainty regarding interval velocities and hence pre-drill depth estimates, because its infill differs greatly from the rest of the overburden.”

“Because of this uncertainty,” Luke says, “the tops did not come in as expected. Even more so, there was no consistency in the error, with some tops coming in shallow and some deep. As such, the geological team started to lose their faith in the pre-drill predictions.”

“Because of this uncertainty,” Luke says, “the tops did not come in as expected. Even more so, there was no consistency in the error, with some tops coming in shallow and some deep. As such, the geological team started to lose their faith in the pre-drill predictions.”

Yet, the tops were very important, because the plan was to cut a 90ft core from the thin reservoir unit, so drilling had to be stopped at exactly the right depth in order to capture the entire sandstone in one coring run.

“We as a geological team were still confident at that stage though, unaware of the dinosaurs lurking in the background. It’s because we thought we were supported by the tools we had at our disposal to overcome the uncertainties related to the pre-drill predictions,” continues Luke. These tools included an uncalibrated resistivity-at-bit tool, which detects gas slightly ahead of the bit, and a backup from gas readings through mud circulation.

“So, when we called coring point, and I opened the core barrels on deck two days later, it was an unpleasant surprise to see that we had cut 88ft of top seal and only 2ft of the target reservoir sand at the bottom of the barrel”, says Luke.

“Looking back,” he says, “we had to admit that the geophysicist had warned us of the uncertainties in the velocity model and hence the time-depth conversion, because of the canyon fill. That’s why he said that we should recalibrate the estimated depth of the top reservoir after hitting the last formation top before reaching target and just use the interval velocity to go forward from there.”

The mistake was that the geophysicist was not part of the operational team running the well. Instead, it was done by the geologists only, who were confident in the tools they had.

“If we had re-calibrated our tops using the interval velocity, we would have hit the target at the correct predicted depth. But instead, we called coring point because we detected gas in a thin sand stringer that was irrelevant to our original target,” Luke admits.

A very valuable lesson to learn.